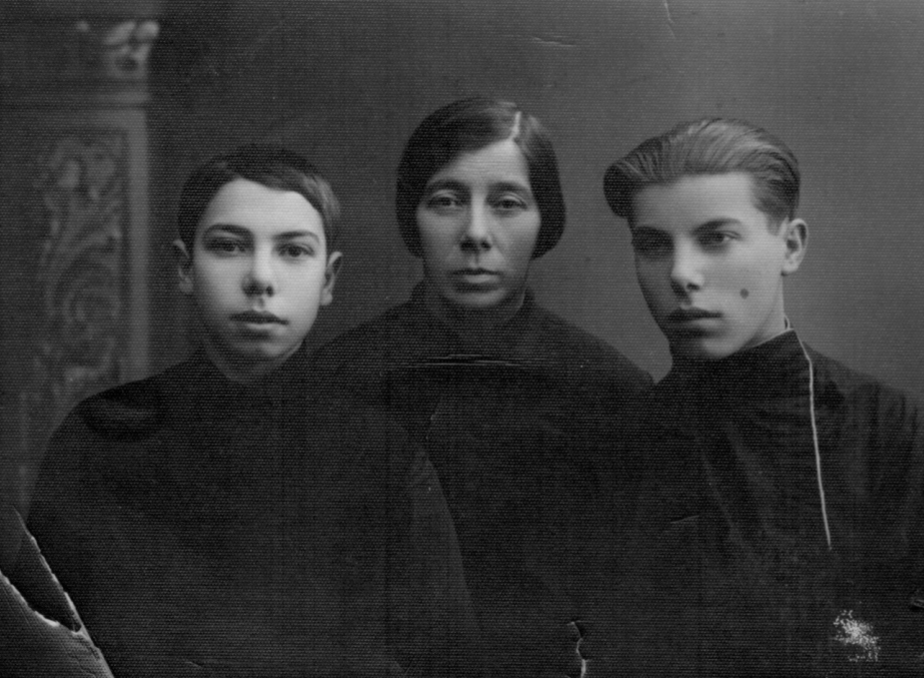

Henry Yelgin was born on March 24, 1915, in Bobruisk, Russia, and grew up in Grodno, Poland. He lived there with his mother, Cila, and his older brother, Abraham, on the city’s outskirts. Henry was not yet born when his father, Samuel Yelgin, died in a poison gas attack by the German Army while serving in the Polish Army during WWI. Cila worked in a Grodno tobacco factory to support her family. After finishing elementary school, the brothers learned trades; Henry was apprenticed to a cabinet maker, while Abraham was apprenticed to a tailor.

At the age of eighteen, Henry was drafted into the Polish Cavalry, where he experienced much antisemitism within its ranks. This often led to military imprisonment as Henry always fought back during these incidents. When Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, Henry’s unit was mobilized. However, Poland was defeated before they reached the front.

In 1939, Germany and Russia signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which partitioned Poland between the two nations. Grodno was annexed to the Soviet Union until two years later when Germany broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. In July 1941, anti-Jewish laws were enacted in German-occupied Grodno. In November of that year, two ghettos were established: Ghetto A and Ghetto B. Together, the ghettos contained around 25,000 Jews.

Since he had a useful skill, Henry worked outside the ghetto as a forced labor carpenter in a German factory. It was during this time that Henry witnessed three atrocities committed by one of the SS commanders (Kurt Wiese):

- The execution of a Jewish worker trying to smuggle a loaf of bread into the ghetto.

- The execution of another Jewish worker smuggling a bottle of brandy into the ghetto. (Note: the SS commander told the man he would not be shot if he drank the entire bottle. However, that was just a ruse to torment him.)

- The hanging of three Jews who tried to escape from the ghetto.

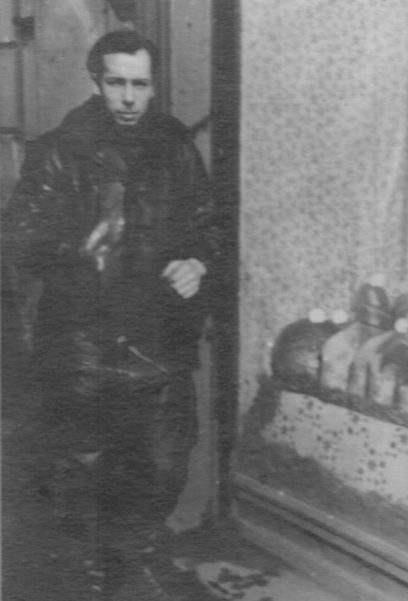

As the Nazis began liquidating the ghettos in the winter of 1942, Henry decided to take action. He had heard the rumors about Nazi death camps and believed that staying in the ghetto would eventually lead to his death. Henry lived in a building that bordered the ghetto fence and was very close to the German arsenal. Over time, he loosened the nails holding a few fence boards in place so that a person could slide the boards aside and leave the ghetto undetected at night. While his friend stood watch, Henry crept out of the ghetto in January 1943 and broke into the German arsenal where he stole the weapons the partisans would need to defend themselves. The following month Henry escaped from the ghetto and smuggled twenty-six people out of the Grodno ghetto in garbage trucks. They hid underneath piles of refuse as the trucks drove out of the ghetto.

The group rendezvoused in the barn of a friendly Christian farmer and traveled by night to the Nacha Forest near Eyshishok (Eisiskes), where Henry was one of the partisan group leaders. Henry was aware of the Bielski brothers, but he believed he had a better chance of survival in a small group where he could make his own decisions. Other Jews from the Grodno ghetto eventually joined Henry’s group, including his future wife, Rita Gurwitz. Henry and Rita fell in love while she nursed him back to health from a sprained leg after being thrown off an aggressive horse.

The partisans’ primary goal was survival and thwarting the Nazis. One of the tactics they employed was to attach an explosive device to a bicycle and leave it on roads frequented by German supply convoys en route to the Eastern Front. When the Germans removed the bicycle from their path, it would trigger the bomb to explode. Russian partisans also recruited Henry’s group to assist with larger raids. They attacked German patrols and placed bombs on railroad tracks to disrupt German communication and transportation.

The partisans’ biggest struggle was survival as their days consisted of scavenging for food and dodging constant raids by German, Lithuanian, Polish, and Ukrainian patrols. During the first summer, they slept on the ground without any shelter from the elements. By wintertime, they had dug holes in the ground and concealed the tops with tree branches covered by snow. As the raids increased, they dug more hiding places and regularly moved to decrease the chance of being discovered. They went on missions to gather food that was obtained at gunpoint from local farmers. Farmers who reported the partisan activity to the Nazis faced reprisals.

One day, a farmer reported Henry’s group to the local SS authorities. This led to a raid on the camp that resulted in the deaths of many partisans. Henry and his comrades later returned to the farmer’s home, held a military trial, and found him guilty. The farmer was shot for reporting them and to send a message to the local population: if you betray the partisans, there is a price to pay.

Henry’s partisan group was liberated on July 7, 1944, by the advancing Soviet Army. Henry and Rita returned to Grodno, hoping that members of their families had survived the Holocaust. Henry’s mother, Cila, miraculously survived, but his brother (Abraham), sister-in-law (Rachel), and their two children (Fannie and Shlomo) were murdered in Auschwitz. Rita was the only survivor of her family. Of the 25,000 Jews of Grodno, only about 200 survived the war.

Henry and Rita were married in Grodno after their liberation in 1944. Since Henry had been a partisan, the Soviets trusted him and put him to work sorting papers in a government archive and later as a guard in the NKVD prison. Through this work and reputation as a partisan, Henry was able to help some prisoners, including his pre-war boxing coach, who had been falsely accused of being a Nazi collaborator. Henry testified at his trial and was instrumental in getting him released.

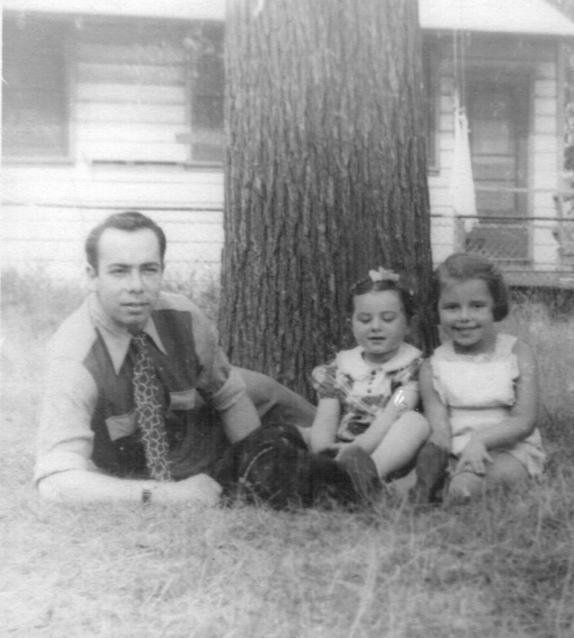

Henry and Rita decided to leave for Germany to escape Stalin and communism. They managed to obtain papers stating they were German-Jews who were displaced during the war and wished to return home. Along the journey, Rita gave birth to their daughter, Esther, in Lodz, Poland, in 1945. They arrived at the Lampertheim Displaced Persons camp in Germany, where they stayed until 1949.

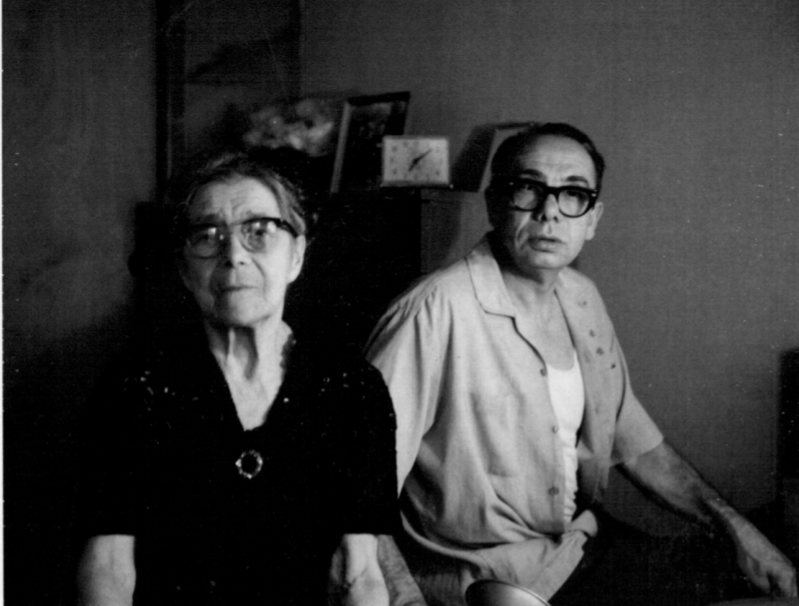

Henry, Rita, Esther, and Cila immigrated to the United States in June 1949, settling in the Boston area where Henry worked as a furniture maker. Henry and Rita’s son, Louis, was born in 1954. In 1968, Rita and Henry traveled to Cologne, Germany, where Henry testified at the trial of the Nazi commanders of the Grodno Ghetto, who all received lifetime prison sentences.

Henry struggled all his life with health issues from the war. This included rheumatic fever from being forced to shovel snow barefoot and PTSD from almost being shot three times by either the Nazis or an antisemitic Russian partisan group. His son recalls many nights hearing his father wake up screaming that the Nazis were coming to shoot him. Henry was open with his family about his experiences and had many Holocaust survivor friends in the Boston area. Henry and Rita had three grandchildren and viewed each succeeding generation as a victory over Hitler.

Henry passed away on August 22, 1978.