Rita Gurwitz Yelgin was born on June 21, 1921, in Slonim, Lithuania, and grew up in Grodno, Poland. She lived with her parents, Aryeh Leyb and Esther (Samsonovitz) Gurwitz, and an older sister Bertha (Gurwitz) Wolynski, who was born in 1905. Rita had two other siblings (Rachmiel and Sarah) who died from scarlet fever in the early 1900s. She also had a brother (Ben Zion) who died in 1913 from tetanus poisoning. During her youth, Rita’s favorite person was her niece, Dolly, who was close in age to her. Rita’s father was an ordained rabbi, but he chose to work as an accountant for monetary reasons at a lumber company in Grodno. Rita was very proud of her rabbinic lineage as she was a 14th generation descendant of Isaiah Hurwitz–a famous Kabbalist from the 1600s who was known as the Holy Shelah.

In 1939, Germany and Russia signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which partitioned Poland between the two nations. Grodno was annexed to the Soviet Union until two years later when Germany broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. In July 1941, anti-Jewish laws were enacted in German-occupied Grodno. In November of that year, two ghettos were established: Ghetto A and Ghetto B. Together, the ghettos contained around 25,000 Jews. Rita and her family were sent to Ghetto B. Rita endured forced labor that included harvesting crops and working in a plywood factory.

On a Friday night in July 1942, Tevke, a young man who knew Rita’s father from the ghetto shul, joined them for a Sabbath meal. He came from the small town of Radun near Vilna and told Rita’s family shocking news about the massacres of Jews in villages around Vilna and deportations to death camps. He also told them about Jews who had managed to escape the slaughter and had formed partisan groups in the forests.

In November 1942, Ghetto B was sealed off, and Jews from Ghetto B were no longer permitted to enter the main city for work. All of the Jews from the villages surrounding Grodno were taken to a holding camp 10 kilometers from the city where the Germans had previously held 20,000 Russian war prisoners who died from hunger and typhus. Rita saw the dead prisoners being carried away on sleds to a burial site. Some of them were still barely alive. In this camp, the Jews from the villages were taken, and transports were assembled for the Auschwitz and Treblinka concentration camps.

When the liquidation of Ghetto B began, Rita managed to escape into Ghetto A in a wagon filled with feather beds. In Ghetto A, Rita was given temporary shelter by a Jewish family. However, the Germans soon began raiding Ghetto A to fill train transports bound for concentration camps. Miraculously, Rita was able to find a hiding place for herself four times and escape the raids.

In the early morning of February 7, 1943, Rita’s father appeared before her in a dream. He spoke to her very sternly and said that she should stop trying to hide in the ghetto. She must escape from this trap and go to the forests near Radun where Tevke had told them about Jewish partisan groups. It was still dark and cold in the small room where eleven people were hidden with Rita. She dressed under the bed covers and slid out of the house quietly.

She came to the barbed wire ghetto gate and saw two German soldiers marching their post. As she hid near the gate, a young boy of fourteen named Cokie ran up behind her. His father was a cattle dealer whom Rita knew very well. Cokie was quite frightened, so Rita explained her escape plan to him. When the German soldiers reached the halfway point of their post, she would lift the barbed wire and walk to the other side of the street – outside the ghetto. Cokie was to wait there until the soldiers had their backs to him on the next patrol cycle and follow her lead.

Rita took off her yellow Star of David, lifted the barbed wire, crawled under, and began walking to the other side of the street. She walked calmly and slowly so as not to attract attention. But, on the other sidewalk, a group of three Polish women stopped and were about to yell out when a German officer appeared and ordered them to move on. He then turned to Rita and said, “Machen sie das shneller … shneller” (Move faster … faster). Rita thought this man must surely have been an angel sent from heaven to help her escape.

She escaped into the nearby woods where she had arranged to meet Cokie. When he arrived, they tore up their identification cards and buried them deep in the snow-covered ground. They waited until dusk to leave the woods. Scared and hungry, they began walking on the main road to Lida, where they had heard there were Jewish partisans in the forests. They walked 16 kilometers that first night and slept in a farmer’s barn. They pressed on at daybreak, moistening their lips with snow for sustenance.

On the third day, they came to the small town of Shutzin (Shchuchyn) – about 65 kilometers from Grodno. The Jews there gave them shelter in two different families’ homes, and Rita was separated from Cokie. She stayed with a wealthy Jewish family. The next day, a Polish peasant woman who had done business with the family came and offered to hide one of their three daughters. Since the daughters did not want to be separated, their father told the woman that Rita was his niece and that she should take her.

Rita stayed with the Polish woman for eight weeks. She dyed her hair blonde, wore a big cross, and went to church with the family every week. One day, the Polish woman’s daughter came to visit her mother from Vasilishok, a town very close to the Nacha Forest where the partisans lived. Rita left with the Polish woman’s daughter. Upon reaching her home, the woman told Rita to stay in the woods about 1/4 kilometer away because her husband was an antisemite. She brought Rita a pitcher of hot soup and bread every day for ten days. On the tenth day, she told Rita that she could no longer hide her because she was afraid of being killed by the Germans if they discovered that she was sheltering a Jew. She took Rita to a road leading into a small village where she could get help finding the partisans.

It was April 1943 as Rita walked along the road that night, luckily stumbling upon three young men who were Jewish partisans on a food mission for their unit. They told her to hide in the woods until they returned. When they yelled “Shura,” that would be the signal to come out of hiding, and they would take her to their camp deep in the Nacha Forest.

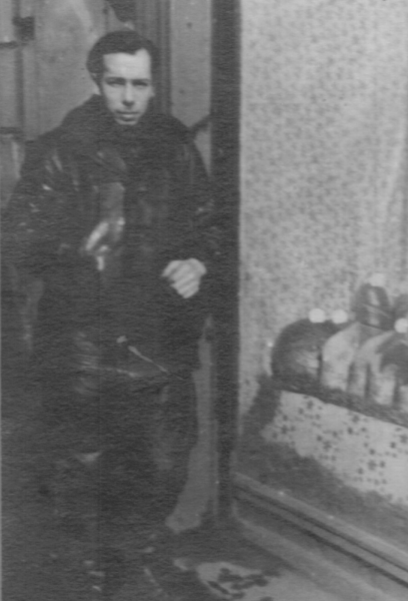

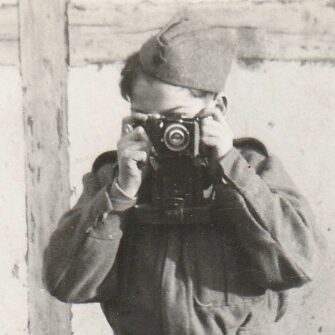

In that partisan camp, Rita met her future husband, Henry Yelgin, who was one of the group’s leaders. He was a true hero who had smuggled twenty-six people out of the Grodno Ghetto in a garbage truck one-month earlier and had broken into the German arsenal to steal weapons that the partisans would need for protection, food missions, and sabotage.

German, Lithuanian, Polish, and Ukrainian patrols frequently raided their camp during the almost two years Rita was with the partisans. The size of their group diminished as people fell in combat. In the early morning of June 16, 1943, they heard gunshots, and everyone began running into the Nacha Forest swamps to escape. Rita hid with a small group that included Henry, his mother, a young woman and her son, and a young couple with a one-year-old baby. Other partisan groups had already pushed out the couple, fearing that a crying baby would give away their position. However, Henry did not have the heart to turn them away. The young mother kept the baby close to her breast, and the child remained quiet throughout the ordeal. As they lay hidden in very thick bushes, they saw a young Lithuanian with a machine gun walking by slowly. Just as he came to their hiding place, he looked away and continued onward. It was a miracle they were not discovered.

During the first summer, they slept on the ground without any shelter from the elements. By wintertime, they had dug holes in the ground and covered the tops with tree branches that were eventually covered by snow. As the raids increased, they dug more hiding places and regularly moved to decrease the chance of being discovered. The men went on missions to gather food which they obtained at gunpoint from farmers and peasants.

Rita was liberated on July 7, 1944, by the advancing Soviet Army. She returned to Grodno, hoping that some members of her family had survived the Holocaust. After several months, it became clear that she was the only survivor. Of the 25,000 Jews of Grodno, only about 200 survived the war.

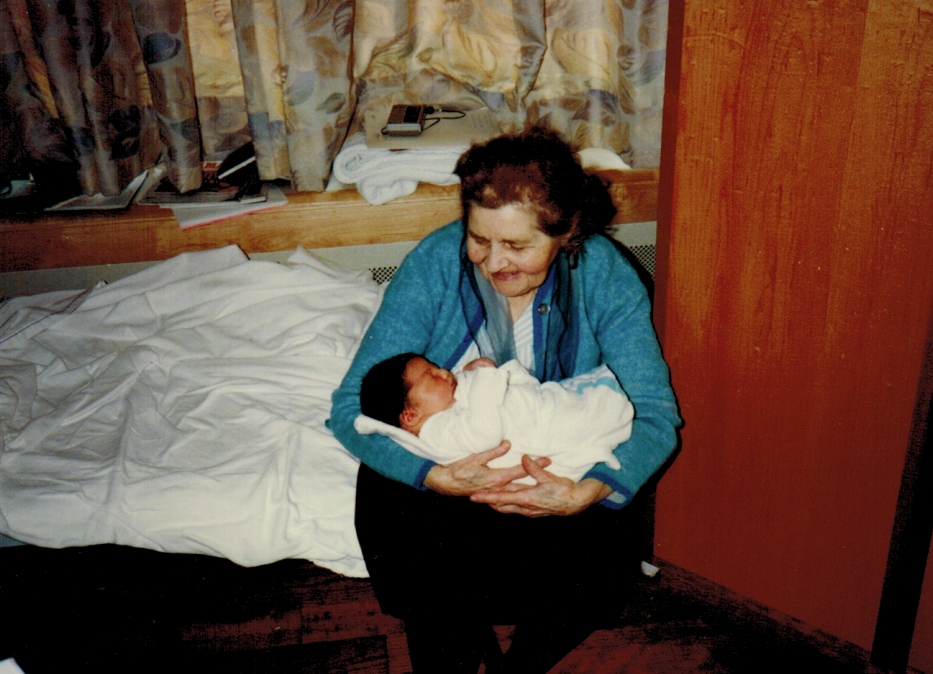

Rita and Henry were married after the war. Not wanting to suffer under Stalin and communism, they decided to leave for Germany. They managed to obtain papers stating they were German-Jews who were displaced during the war and wished to return. Along the journey, Rita gave birth to their daughter, Esther, in 1945. They arrived at the Lampertheim DP camp in Germany, where they stayed until 1949.

Rita, Henry, and Esther immigrated to the United States and settled in the Boston area where they had a son, Louis, in 1954. In 1968, Rita and Henry traveled to Cologne, Germany, where Henry testified at the trial of the Nazi commanders of the Grodno Ghetto, who all received lifetime prison sentences.

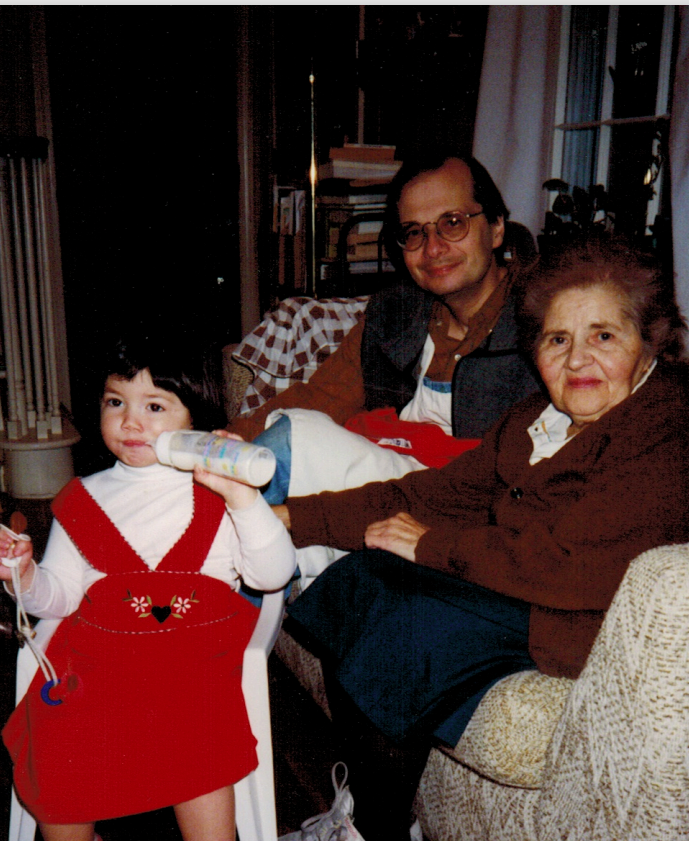

Rita struggled all her life with health issues from the war. She was open about her Holocaust experiences and often shared her survival story with family members and social groups in the greater Boston area. She also provided her Holocaust testimony to Steven Spielberg’s USC Shoah Foundation. Rita was proud of her children and grandchildren and viewed each succeeding generation as a victory over Hitler.

Rita passed away on March 1, 2010.