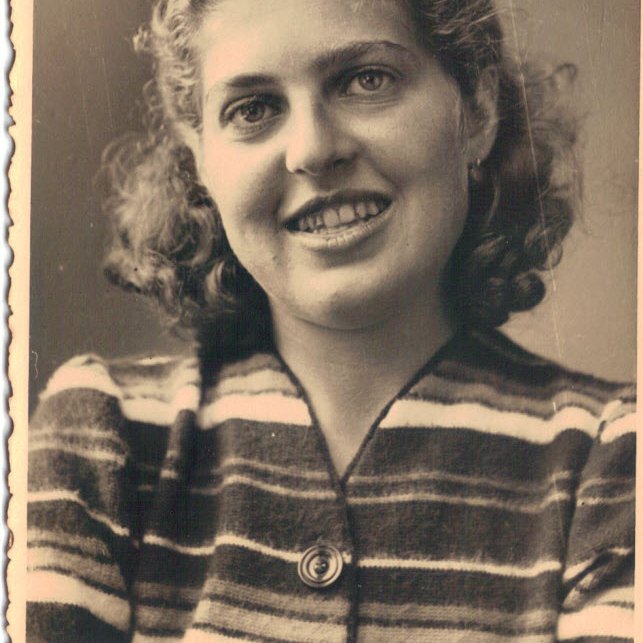

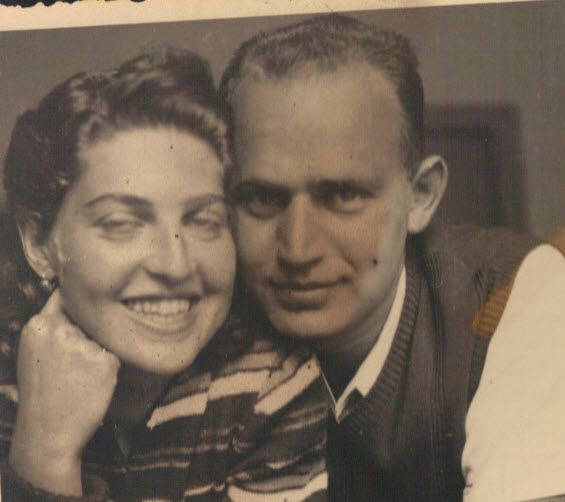

Zdenka Novak, born Zdenka Steiner in Zagreb, Croatia in 1919, was the sole survivor of her family. She lived a protected life full of culture, music and literature. In 1939, she travelled to Paris to study languages, but returned to Zagreb later that year after hearing the news of France’s war mobilization. Upon her return, she married Fritz Brichta, with whom she had been romantically involved.

Her father, Lavoslav, was the vice president of the Jewish community of Zagreb and served as an officer in the Yugoslavian army during the First World War. He felt very confident that nothing would happen to him and his small family, so they did not flee as was recommended by his colleagues in the United States; however, in April 1941, the Nazis entered Yugoslavia and they established the Ustashe government in Croatia as their puppet government. When the Ustashe came to power, they established antisemitic laws that targeted the Jews in Croatia. When the clouds of hatred and antisemitism began to thicken, Zdenka’s family had a meeting in the living room of their beautiful apartment in Zagreb. Mira, Zdenka’s younger sister had a non-Jewish boyfriend who knew about the plans of the local Ustashe leaders to kill all the Jews, so he tried to convince her father to escape. Her father refused and said that it was too early and that nothing will happen. Mira screamed out of frustration and fear and Zdenka sided with her father.

Zdenka was eventually separated from her family when they were forced to evacuate. Zdenka’s father was deported to the Yasenovac Concentration camp, where he was killed. Her mother Elza and aunt Mira were killed on the Island of Pag. Her husband too was murdered on the island of Pag. Just 21 years old, orphaned and widowed, Zdenka managed to escape in a train from Zagreb to the coastal town of Susak (Rijeka) in Croatia, which was occupied by the Italians. There she lived in hiding and worked for the local Communist resistance group to combat the Nazis and their collaborators. When Germany took over the rule of this Italian territory in 1943, Zdenka feared for her life and walked for about 22 miles to a town called Cirkvenica where she joined a partisan group that was part of Tito’s army.

In her own words: “I started my journey to reach the partisans who were stationed near Crikvenica, some thirty five (22 miles) kilometres away from Susak. There was no other way to reach them but to walk. In normal circumstances nobody would undertake such a ‘Promenade’, although it is a beautiful country along the Adriatic coast with the many little bays and curves – but not in times of war! The day seemed endless, no vehicles, no people on the way, only gunfire and from time to time, shells flying over my head.

At dusk when I arrived at Crikvenica, I was tired and exhausted but happy to have reached my destination. Crikvenica, a formerly fashionable resort, was crowded; men and women in uniforms circulated busily in the streets. The Allies delivered all kinds of equipment to the partisans, mostly by parachute. After a few days they had to move because German forces were close by.”

Because Zdenka was proficient in seven different languages she was given the responsibility for deciphering secret messages for the partisan groups – a task essential for their success. The transition to becoming a partisan was not easy.

In May, 1944 the Germans decided to destroy the partisan movement and everyone had to disperse. Zdenka escaped with two other young women from her group but soon they too had to separate. This escape was one the most powerful experiences in Zdenka’s life. She had to walk for almost three days and three nights with very little sleep. When Zdenka nearly collapsed from exhaustion, she decided to stay in a village nearby while the other partisans she was with continued walking. A miracle happened that evening; in the village where she stopped, she ran into Fritz’s parents (who had become refugees). Zdenka decided to stay with them and they lived together for the next few months. It was one of the most memorable experiences in her life. Later Zdenka decided to rejoin the partisans.

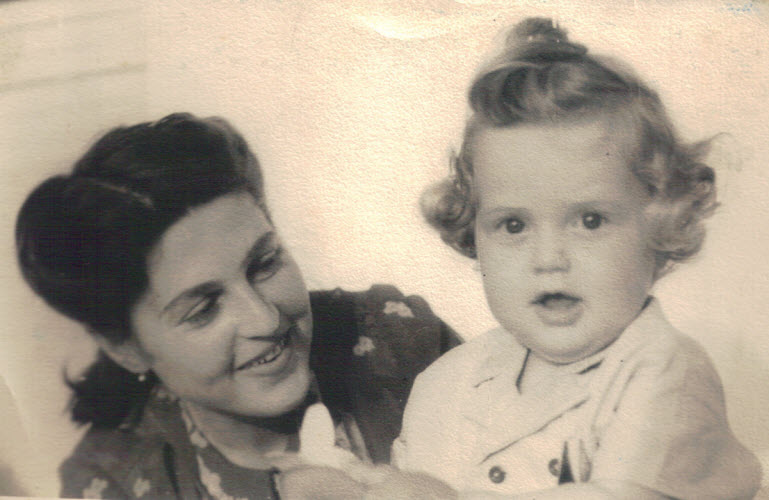

When the war ended, Zdenka returned to Zagreb, but she did not recognize her town or the way of life. She was very disappointed in the unethical new government of Yugoslavia and could no longer stay in that country. After marrying her lawyer, Zvonko Matersdorfer, they changed their name to Novak. The couple immigrated to Israel in December 1948, and soon after, in February 1949, their son Dani was born.

Zdenka studied English literature in Haifa’s university and lead a meaningful life full of music, literature and friends. She had two beautiful daughters and two great-grandsons. Since her death in 2005, her son Dani has made it his mission to share her story so that the world never forgets what happened to the Jews of Yugoslavia and Europe. The house on the Island of Pag, where Zdenka’s mother and aunt were raped and murdered, still stands and today serves as a school; however, no one mentioned what happened in it, as the original owners were murdered. Even today, local residents deny the atrocities that took place there. Dani will continue to tell his mother’s story so the world will remember and justice will prevail.

Read Zdenka Novak’s full biography here.