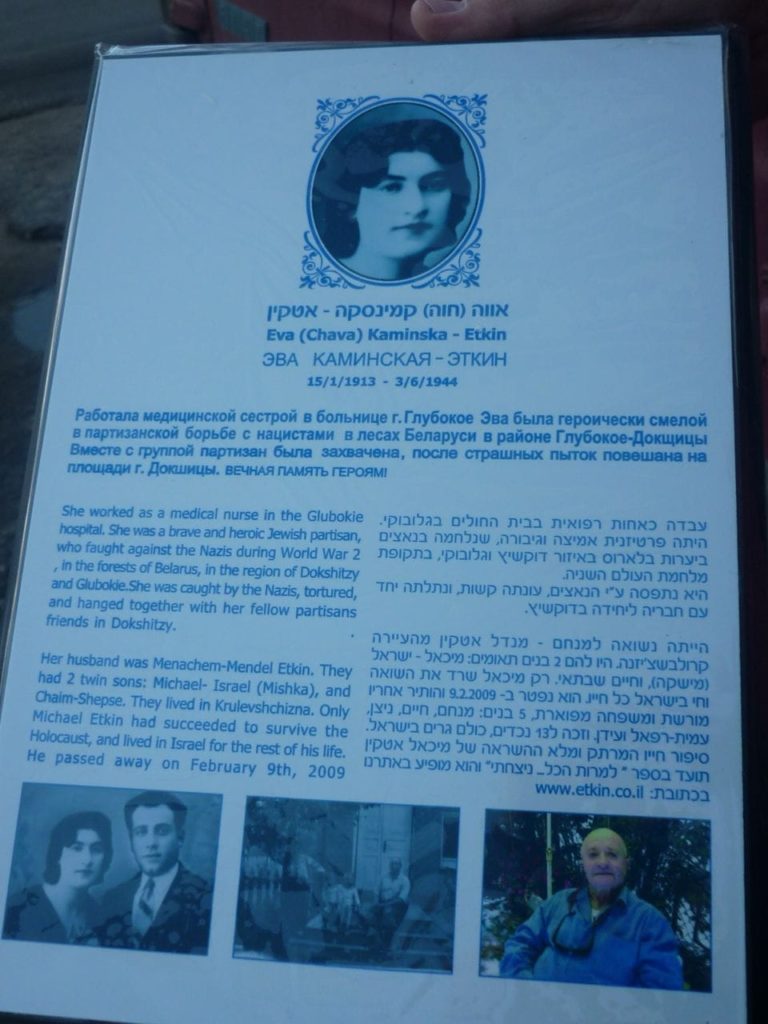

Michael Etkin and his twin brother, Chaim-Shepse, were born on December 25th, 1932 in Krulevshchizna, in the North of Belarus. Their mother, Eva, was a nurse at the Glubokie Hospital while their father, Menachem-Mendel, managed multiple family businesses including a sawmill, a flour mill, restaurant, and furniture carpentry. During the twins’ early childhood, they knew only wealth and happiness as they were showered with love by their parents and extended family. They lived in a large house adorned with beautiful furniture, carpets, dishware, and paintings. Michael played in their expansive yard, surrounded by cherry and birch trees, rose bushes, and an array of flowers.

Michael’s life drastically changed with the sudden death of his father in March 1941 at the age of thirty-two, just a few months before the Germans arrived in Krulevshchizna. The Germans broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with the Soviet Union and invaded Russia in June 1941. In October, a German truck arrived at the Etkin home to move them into the Glubokie Ghetto along with eighty other Jewish families who lived in Krulevshchizna. As the truck drove away, Michael looked back at the yard, trees, and the paved stone lane. This was the last time he saw his childhood home.

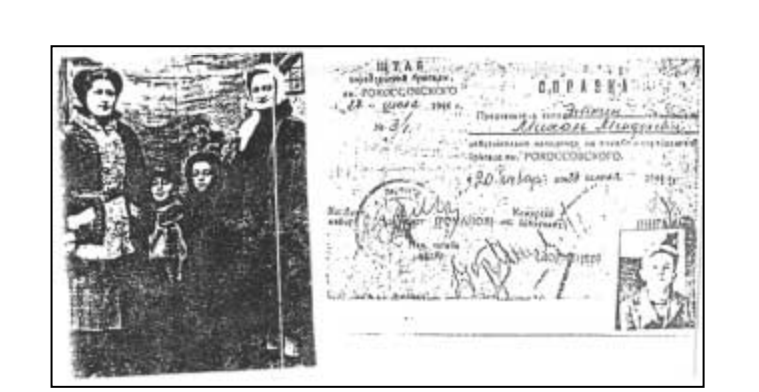

After residing in a comfortable house with many rooms, Michael, Chaim-Shepse, Eva, and their Aunt Lea were suddenly living together in one small room in the Glubokie Ghetto. No one could enter or leave the ghetto without a permit from the Germans. Whoever was caught outside of the ghetto took the risk of being thrown in prison or killed. However, without any hesitation, Eva decided to resist the Nazis. Her sister, Lea, cared for Michael and Chaim-Shepse as Eva joined the October Partisan Brigade where she served as a nurse in the medical unit, caring for the injured in the region of Dokshitsy & Glubokie.

Michael missed his mother’s presence, her voice, her smile, and her beautiful stories. The twins were constantly asking: “Mama Liubmaya, gdye ti?” (Dear mother, where are you?) Eva returned to the ghetto and visited the twins and her sister periodically, giving them updates on the war. She warned the twins, “If German soldiers come here asking where I am, tell them that mother is not at home now, that you are also waiting for her, and you don’t know where she is. Don’t tell them anything!”

The twins kept silent when their mother’s whereabouts were questioned. Every few days, German soldiers entered their small room, suspecting that Eva was helping the partisans. Despite their uniforms and guns, the twins remained steadfast. Michael and Chaim-Shepse informed the soldiers that their mother was not around, and they did not know where she was. Whether they believed them or not, the soldiers left them alone. Michael later discovered that his mother helped smuggle pistols, grenades, and ammunition to the partisans.

On August 20th, 1943, the Nazis destroyed the Glubokie Ghetto after a week of armed Jewish resistance. Michael saw the Nazis shoot Jews with machine-guns as they fled into the forest. Michael and Chaim-Shepse held their aunt’s hand as they stood only twenty meters from the ghetto’s wooden fence. “We must run immediately!” Michael screamed, realizing that their time was running out. But Aunt Lea, frozen with fear, stood still. “We are not going anywhere,” she told him. “We will stay here and live or die together.”

“Can’t you see that they are killing people?” Michael questioned, suddenly feeling like an adult at just eleven years old. “Let’s run!” But Aunt Lea refused. “Hold my hand firmly and don’t move,” she instructed. At this moment, Michael knew what he must do. He released his hand from his aunt’s grip and ran through the broken wooden fence of the Glubokie Ghetto. He ducked under the tanks’ pipes and joined the fleeing Jews who were running towards the forest. It was the only chance he had of staying alive.

Bullets whistled past Michael as he ran. He did not stop, even when he felt a sharp pain in his foot. With the forest only 500 meters away, Michael’s strength began to wane. The wound was more severe than he thought. The bullet had crushed bones and flesh in his foot. Michael lay wounded in the field, his eyes searching for someone to help him. A man named Motke Kraut stopped and carried Michael on his back to the safety of the forest. Motke took off his shirt and bandaged Michael’s wounded foot with it. Michael could hear echoes of the German tanks and machine-guns in the ghetto where Chaim-Shepse and Aunt Lea stayed behind, along with the rest of the Etkin family who was killed there.

A few weeks later, Michael’s foot became infected. Motke Kraut took Michael to a family in a nearby village who knew Michael’s father, Menachem, and took him in without hesitation. One day, German soldiers searched the house. When they questioned who Michael was, the family said he was their son who was very ill. The soldiers left without any further questions. Once again, Michael’s life was saved.

Three months later, Motke brought Michael back to the forest to join the Rokosovsky Partisan Brigade where he served for seven months. He helped around the camp and carried explosives when the partisans bombed German railroads. During his time with the partisans, Michael could not stop worrying about his mother. Then, Michael received a letter from her that was written on a brown paper bag in Yiddish. The letter said: “My dear son, I found out that you are in the forest not so far from me. Be a good boy. Behave well. We will meet each other soon. I love you very much – your mother.”

Eva had heard from a partisan that he saw a red-haired child in one of the partisans’ camps. She assumed it was one of her twins but was not sure which one. The letter gave Michael strength and renewed his hope. When Michael informed the partisans that he was going to search for his mother, they would not let him go for fear he would be caught by the Nazis.

By July 1944, the fighting had ended in Belarus. The Nazi threat had been removed and Michael was able to travel safely by train as he searched for his dear beloved mother. Her letter remained in his pocket as a sign of life. Michael believed she was still alive and was waiting for him in one of the villages or shtetls (small towns) in the area. Knowing deep down that Chaim-Shepse and Aunt Lea didn’t survive, he let himself hope he would find them as well.

During Michael’s train ride to Kurinyetz, an unknown Russian soldier approached him. “Aren’t you Eva Etkin’s son?” he asked. Eva and the Russian soldier had fought together in the partisans, and she often spoke of her red-haired twins. “Your mother was a wonderful woman, and an excellent fighter. She was a hero,” he said. The soldier could not bring himself to tell Michael the truth—that Eva had been murdered by the Nazis.

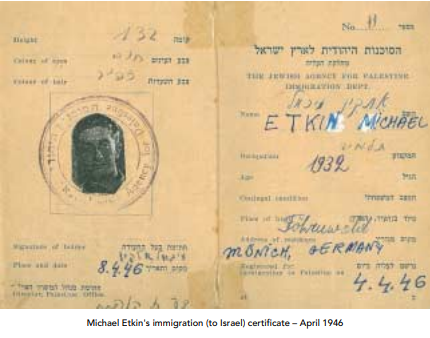

Michael managed to locate his uncle Tana Hodosh and cousins, Zelig and Hershel in Kurinyetz. Michael was in and out of their house as he continued searching for his mother. Tana Hodosh offered Michael the option to travel with them to America, yet also offered to board him on an orphans’ ship heading to Israel. The ambiguity reflected his attitude towards his nephew, and Michael decided on Israel.

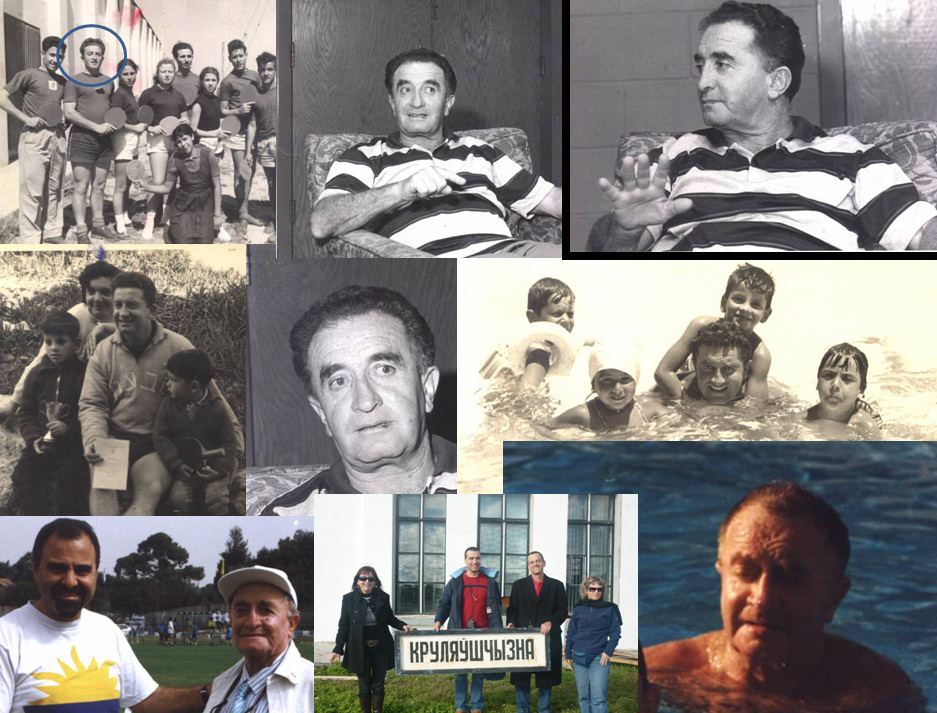

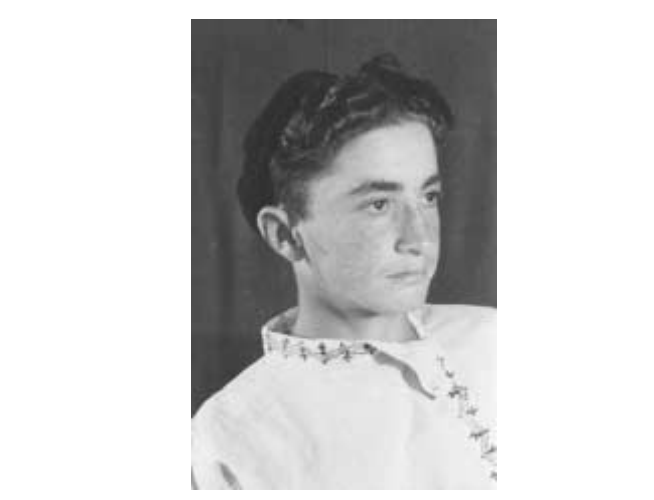

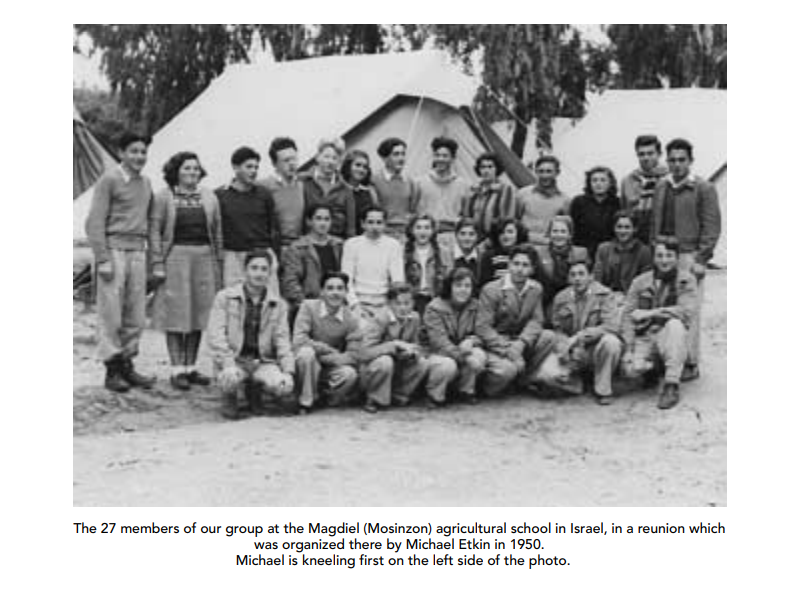

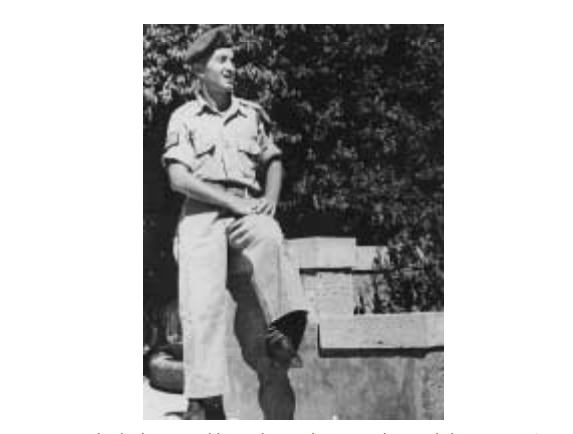

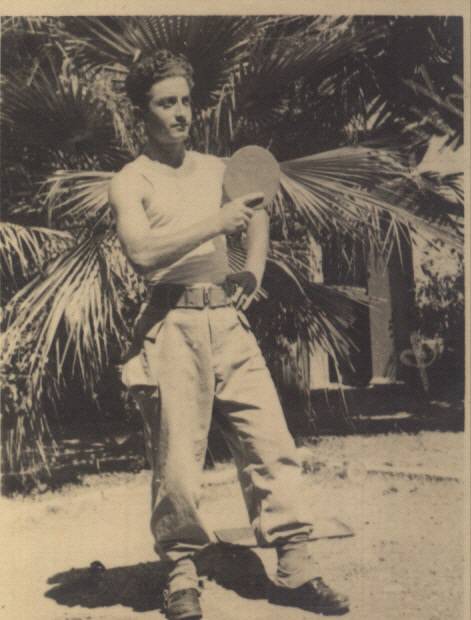

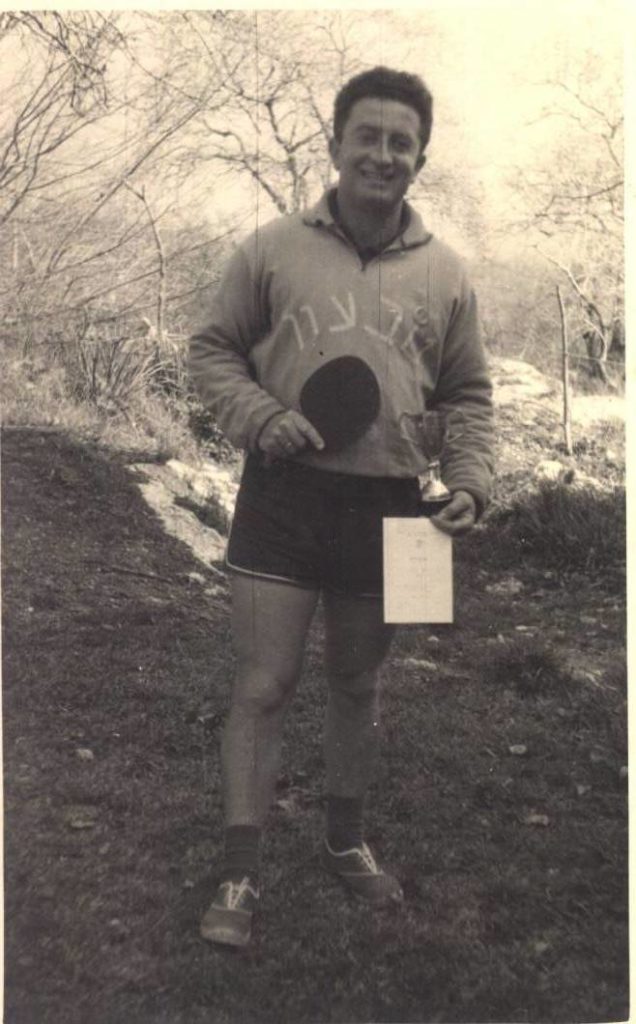

Once he arrived in Israel, Michael studied at an institution for young immigrants who survived the Holocaust before living and working on a Kibbutz. On March 11th, 1951, Michael was drafted into the Israeli Army for two and a half years. He then graduated from the Wingate Institute with a certificate as a physical-education teacher and a certified coach.

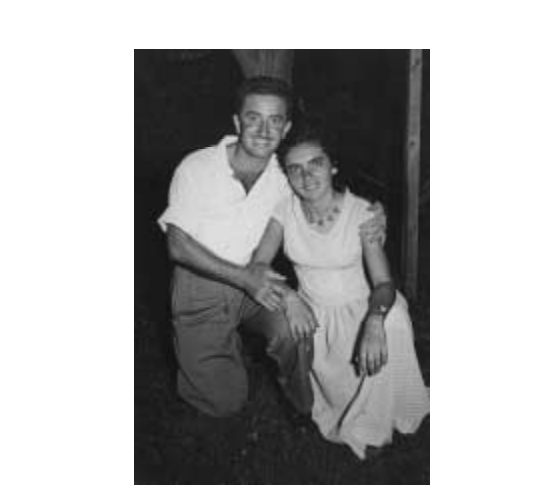

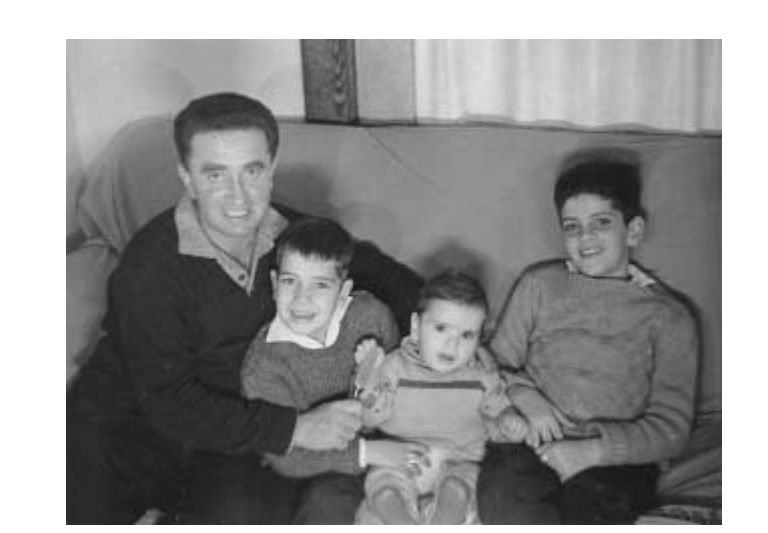

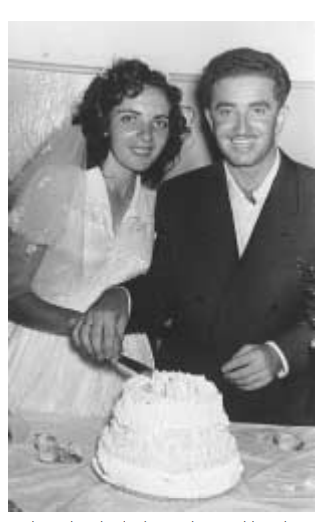

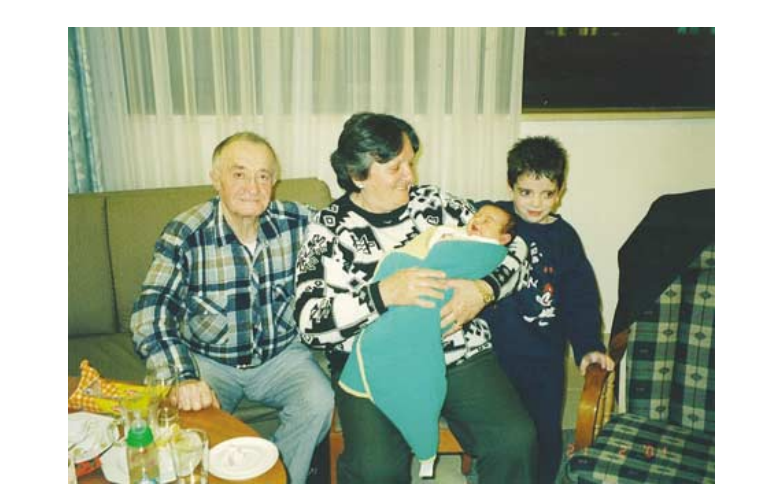

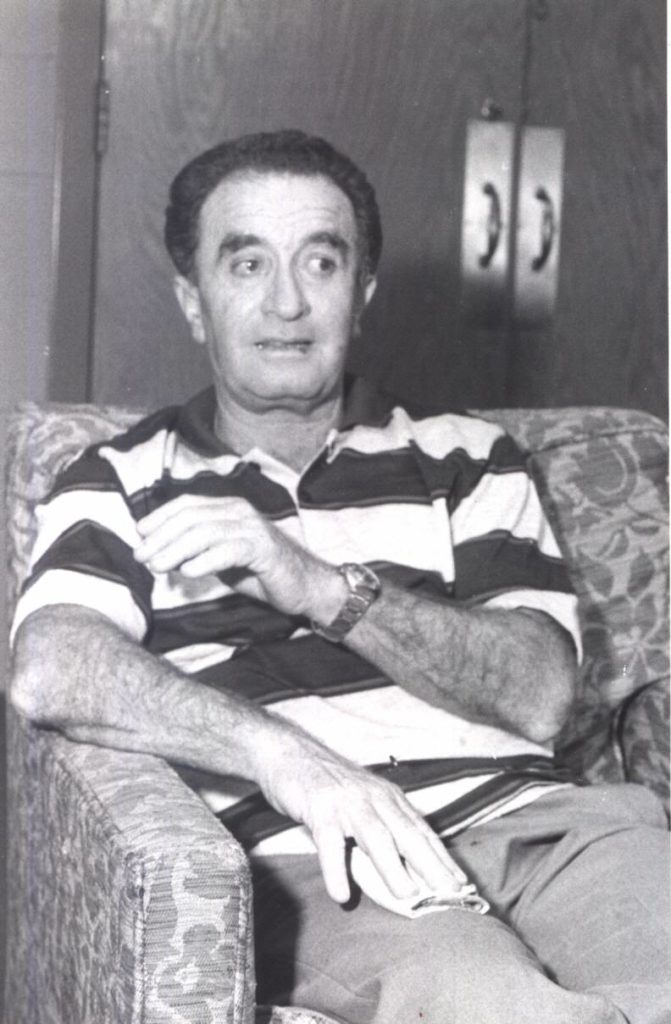

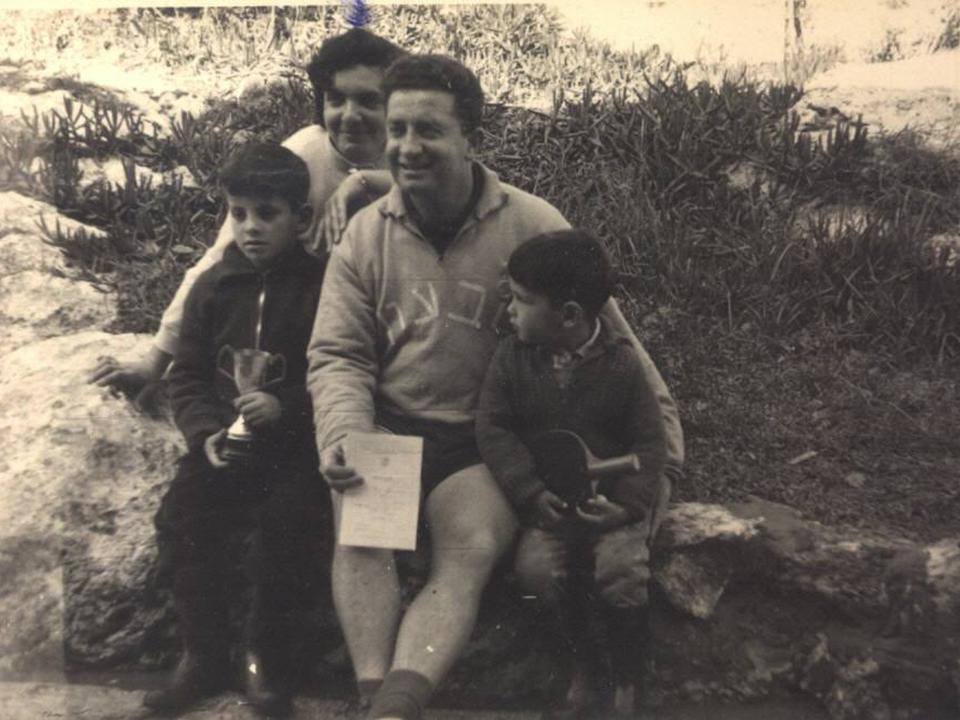

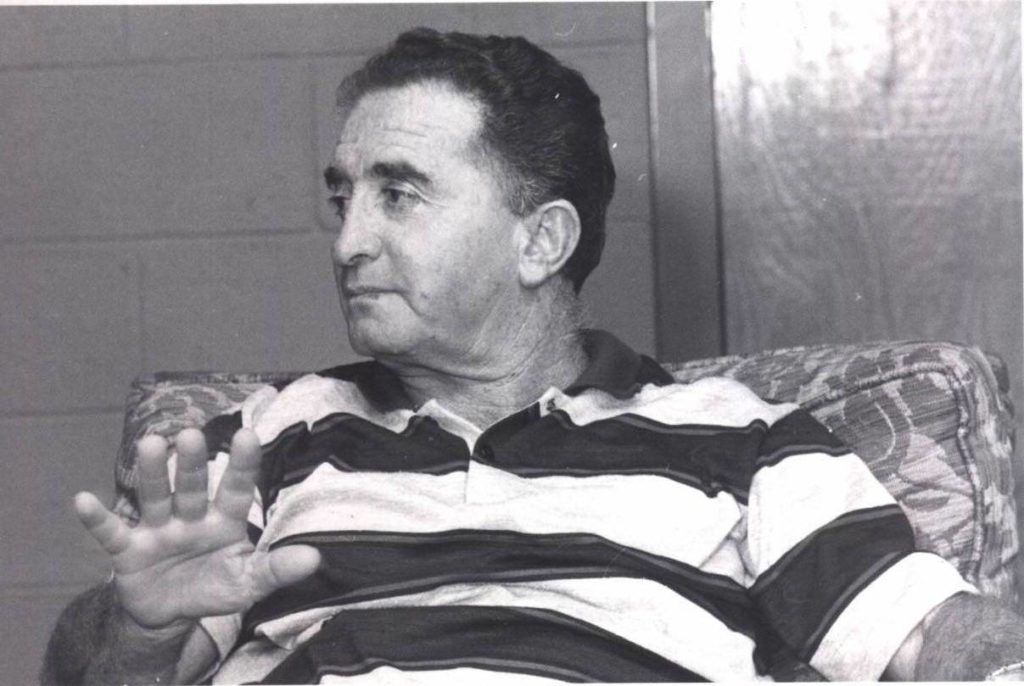

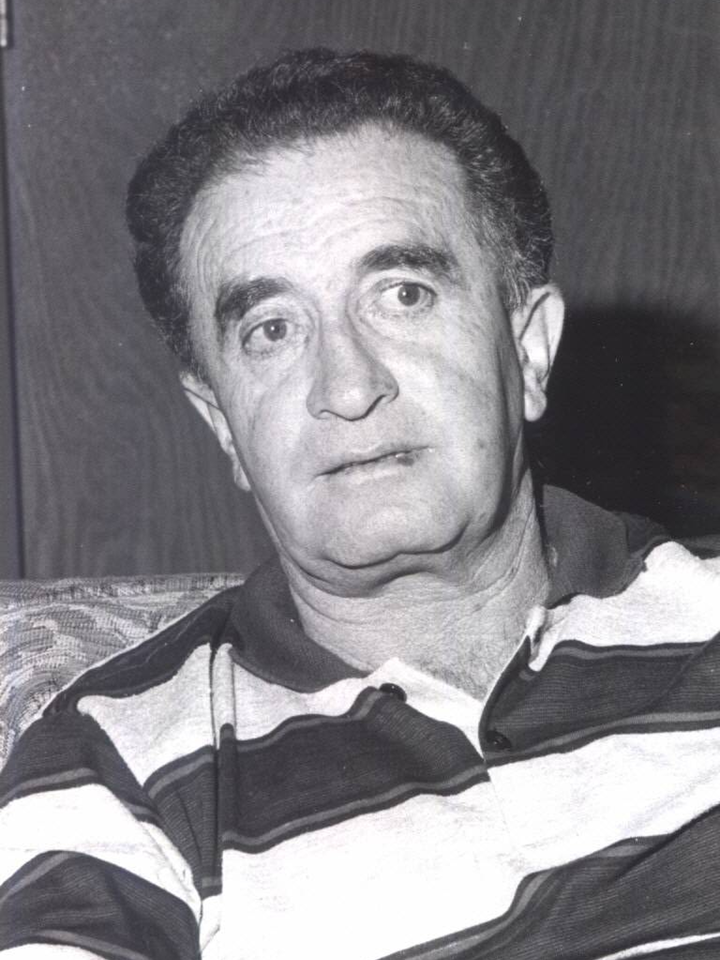

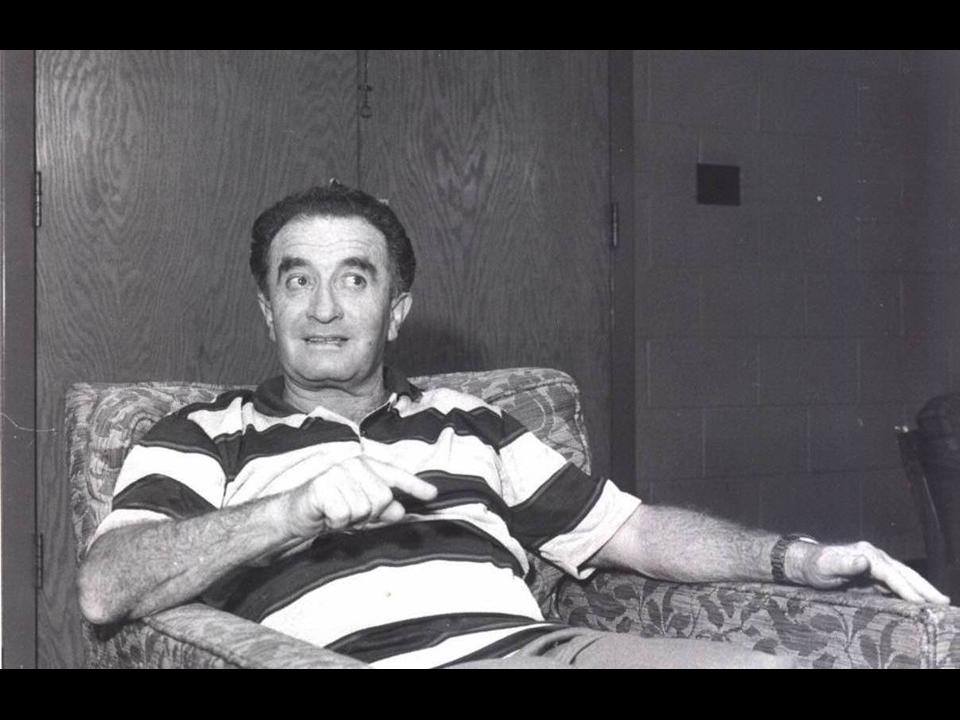

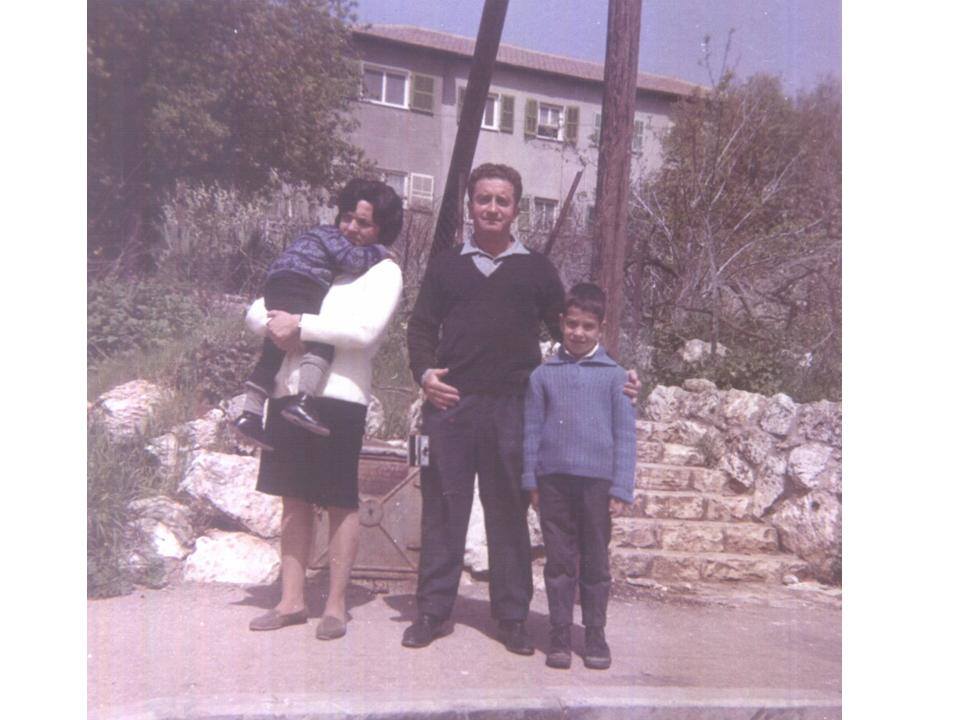

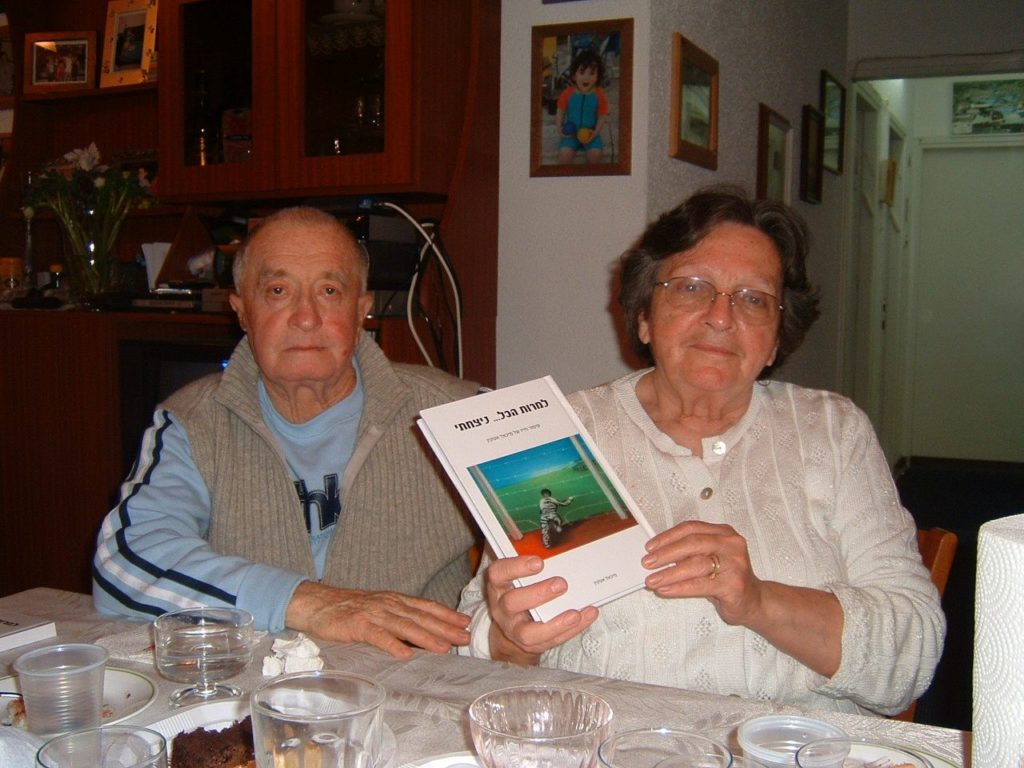

Michael met Rivka Levy in 1954, and they were married on August 20th, 1956, thirteen years after the Glubokie Ghetto was destroyed. They raised five sons: Menachem, Haim, Nitzan, Amit-Rafael, and Idan. Michael became a senior teacher and gave lectures at the Wingate Institute. In 1982, he retired from the Ministry of Education, but continued working for another sixteen years in many other jobs, such as teaching in the Amal schools (Geography, English, and Physical-Education), lecturing at the Holocaust Studies school in Haifa, in a religious Talmud-Tora, and the Gilon-Misgav school, and coaching volleyball.

Michael was the only one who survived the Holocaust out of twenty-five people in the Etkin family. He searched for his beloved mother his whole life, but only when he reached the age of sixty-five did he receive answers from the Belorussian embassy in Israel regarding her death. Although Eva’s place of burial is unknown and she has no grave, Michael wanted a memorial built for her and wished to tell his mother that “despite everything – we had won.”

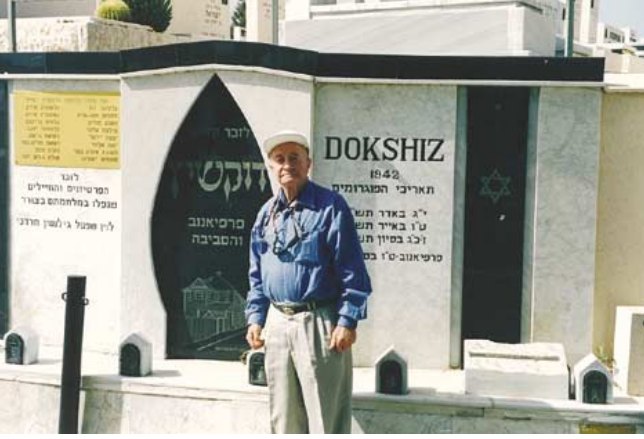

Michael Etkin passed away on February 19th, 2009 at the age of 77. In 2009, Michael’s sons, Menachem and Haim, participated in a Roots Trip to Belarus along with their wives and Menachem’s son. They erected a memorial monument in the Jewish cemetery of Dokshitsy in memory of their grandmother. On the back of the memorial is an aluminum plaque bearing the names of their family members who were killed during the Holocaust.

While in Belarus, they also visited the Globokie Hospital where Eva worked as a nurse until October 1941. They gave the director Eva’s photograph which was put on display in the hospital. “My father always told us that he would like to bring a photo of his beloved mother to the Glubokie Hospital and request that it will be displayed there,” said her grandson, Menachem. “So, we fulfilled one more of my father’s dreams.”

Menachem preserves the legacy of his grandmother and father by giving talks to thousands of students and soldiers throughout Israel. He is dedicated to sharing their memory and has translated his father’s memoir “Despite Everything – I Had Won” for English readers around the world.