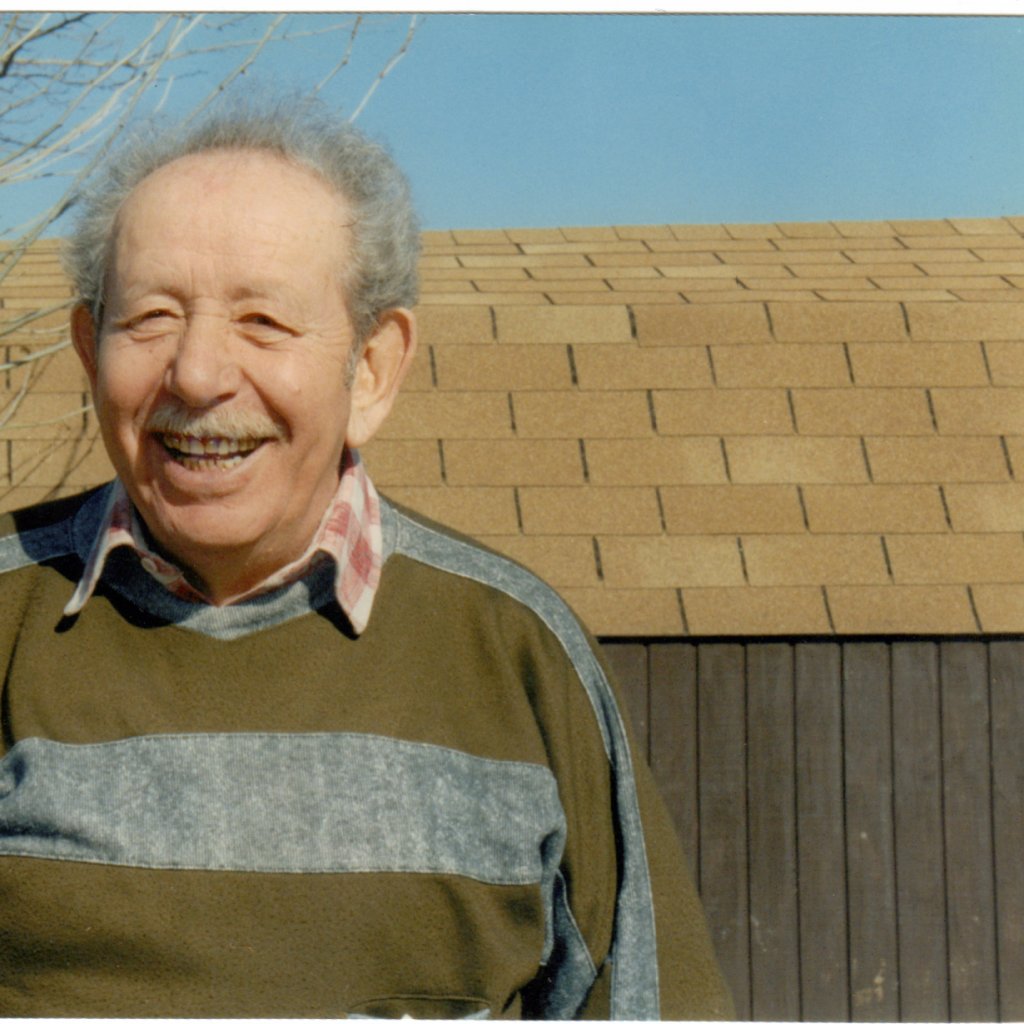

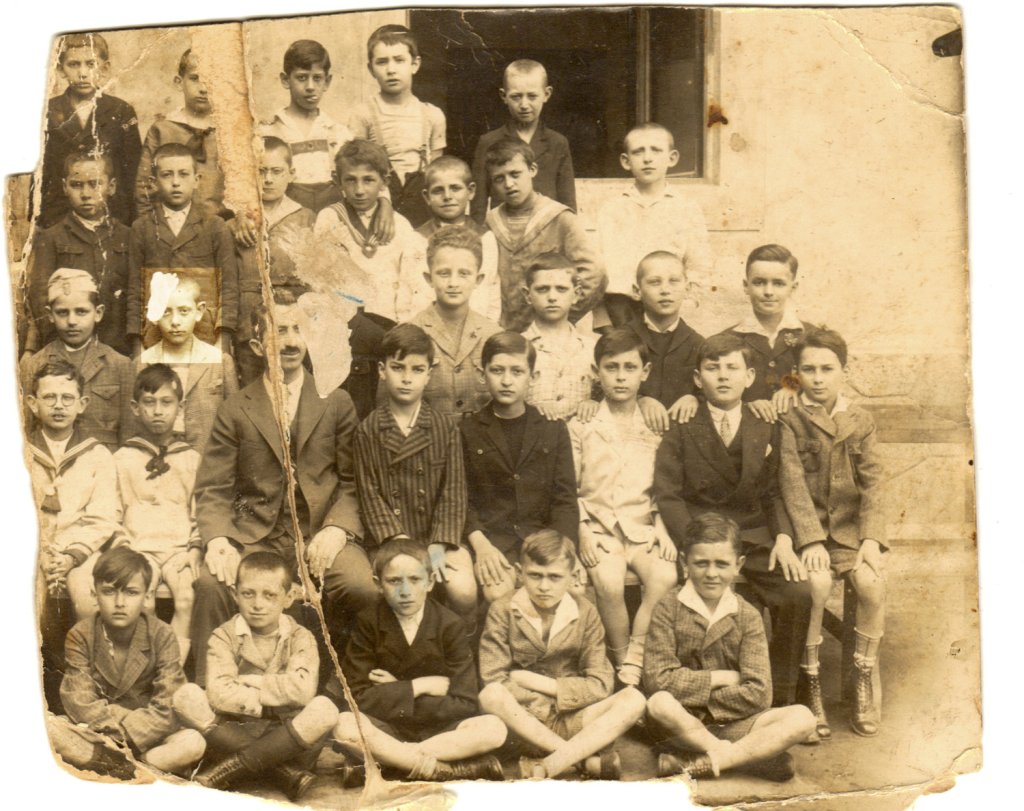

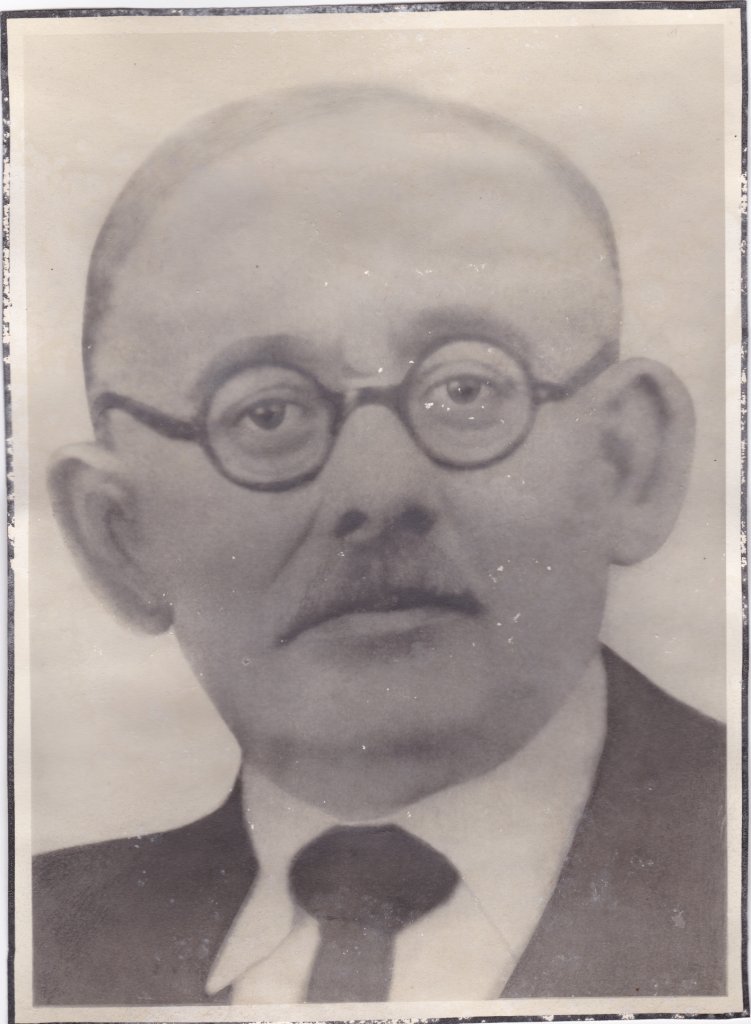

Laszlo Mittelman was born in Debrecen, Hungary in 1919. His parents were relatively poor, but they managed to put food on the table for their four children and once a year, for Passover, buy them each a new pair of shoes. Laszlo’s father was a furniture maker, a skill passed down through several generations, and Laszlo, as a child, would go help out and learn the trade. He was quite naughty and would often get in trouble. He wasn’t very interested in studying, preferring to play soccer with his friends and often getting into fights with antisemitic bullies.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Hungary was sympathetic to the Nazis. Immediately all men over 18 had to enlist in the Hungarian army. The Jewish men were made to wear yellow armbands and were soon forced into hard labor in work battalions. These battalions were taken all over Hungary to build housing and barracks for the eventual invasion of the German army. “The Hungarian army who oversaw the Jewish work battalions were sometimes worse than the Nazis,” Lazlo recalled. One of the places that Laszlo was taken was a small city called Szolnok. That is where he met his future wife, Magda. He was able, on occasion, to sneak out of the camp by bribing the commander with cigarettes and alcohol to visit his Magda. On one of these occasions, he returned too late for roll call. His punishment was hanging with his arms tied behind him while lifted off the ground. Rather than give the officer in charge of the punishment satisfaction, Laszlo laughed at him. When the doctor came to check on him, he forced the officer to cut him down. But because Laszlo was laughing, the officer made him run around the barracks for another hour and do push-ups to teach him a lesson.

After ten months of hard labor, Laszlo’s unit was sent to the Russian Front. This was the border between Poland and Ukraine which was under Soviet occupation. There he was under German control. The Germans used his unit to lay mines along the border in anticipation of the Soviet army’s attempt to liberate Poland. Many of the unit members were killed by these mines because they weren’t marked well, and they would accidentally trigger them. By 1944, after many months of moving along the border, the German army was ordered back into Poland because the Soviet military was pushing across the border. As they marched, a wagon full of stolen merchandise that the Germans had taken broke down. The Nazi in charge knew of Laszlo’s skills as a carpenter and told him to pick a couple of men to repair the wagon and follow them when he was done. The German and the rest of the unit moved on. Laszlo and his friends were left behind.

This was his opportunity to escape. The three men ran into a nearby forest and came upon a group of partisans. They explained that they were Jewish slave laborers and had just escaped from the Nazis. One of the partisans told them: “never tell anyone that you are Jewish again.” He invited them to join the group and fight the Nazis. He explained that they went out mostly at night, working in small groups to sabotage and do whatever they could to help liberate Poland. Laszlo and his friend joined. The partisans were comprised of all kinds of people. They were Polish, Hungarian, Russian, Slovakian, men, women, Christian, Catholic, and Jewish; anyone who wanted to fight. The partisan group was part of the Polish Home Army under the leadership of the Polish General Bor Komoneski. General Bor, as he was known, was a double agent. He was working with the Germans undercover and passing on intelligence to the British Army. Laszlo was especially impressed with the women in the group. He said he had never seen such bravery.

As the Soviets were nearing Warsaw, Laszlo’s group was there to help push the Germans back. The Ghetto had already burned, but the partisans were there helping with the Warsaw uprising. On one of these raids, Laszlo was shot. His friend from the labor brigade, who escaped with him, left him there to die. He was first shot in his legs. But as the Germans were retaliating, he was shot a second time. There were thirteen bullets in his body.

The Germans picked him up because he was wearing a Hungarian army uniform, and they thought he was caught in the battle crossfire. They took him to a field hospital, where they bandaged him up and then sent him to a hospital in Łódź. The doctor there saw his wounds and said his leg needed to be amputated. Laszlo refused. He said: “If you can’t save my leg, don’t do anything.” The doctor operated on him and saved his leg. But when Laszlo woke up from surgery, he found that he was in a separate room from the other German patients. The doctor realized that Laszlo was Jewish. He quarantined him. The doctor came two to three times a day and nursed him back to health. But Laszlo knew he had to get away from the hospital. He asked the doctor to teach him how to use crutches, and after a few weeks, as the Allies were bombing Łódź, Laszlo walked out of the hospital.

After several months he arrived back in Debrecen. Hungarians had stolen and occupied the home he lived in with his family. He was able to find a house with the help of an old schoolmate. This was lucky because his mother and sister, with her five-year-old son, arrived the next day. It was a miracle they were alive. He also received a telegram from Szolnok from his girlfriend saying: “I’m back, come and get me.” Right away, he went to Szolnok to find Magda, who survived both Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen. They were married within a week.

In 1949, with the Soviets now occupying Hungary, Laszlo and Magda and their two-year-old son left for Israel. With the help of the Bricha organization, they made their way through Austria and Italy and then by boat to Medinat Yisrael. They were sent to an absorption center in Ramla, an old Arab village, and Lazlo was immediately enlisted into the army to fight for the new homeland.

Magda and Laszlo’s daughter was born in Israel. After two years in Ramla, they moved up to the north to a moshav in Galilee on the border of Syria. There they had a farm with chickens and cows and an orchard. But the border was dangerous in the late 1950s and early 60s. They were shot at by the Syrians almost daily. Laszlo was still carrying several bullets from his partisan days and was tired of war and anxious about his son, who would have to serve in the military.

In late 1964, Magda and Laszlo immigrated to the United States. Laszlo joined his brother, who was already in the United States and worked with him, making old-world European furniture just like their father and grandfather had.

Magda and Laszlo (Les in the USA) lived in New York, Florida, and Texas. They had four grandchildren. Laszlo never lost his mischievous ways. He had a smile and a twinkle in his eyes until the day he left this life.