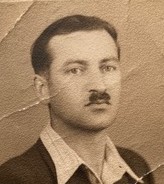

Bernard (Berel, Boris) Novick was born August 14, 1922, in the small town of Marzinkance, Poland, deep in the forests near the convergence of Poland, Belarus, and Lithuania. He lived with his parents, Yehuda ben Dov and Sarah Eshe (Rosenlud), and five siblings: Zelda, Zelig, Shmuel, Esther, and Noach. Berel was the second oldest and only five years old when his mother passed away. His father was the shtetl’s blacksmith, and Berel left school by the age of twelve to work alongside him to help support the family. The skills and strengths he got working with his father enabled him to survive what was to come.

In August 1939, when Berel was seventeen years old, Germany and Russia signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which partitioned Poland between the two countries. In September of that year, Marzinkance was occupied by the Soviets. The life and freedoms Berel knew vanished under Soviet control. In June 1941, Germany broke its pact with Russia and invaded the Soviet Union. Soon the German Army marched into Marzinkance, enacted anti-Jewish laws, requiring Jews to wear the Star of David and form a Judenrat (a Jewish Council under German control).

The Germans forced Berel’s family and all seventy Jewish families in their community into a ghetto at the west end of town, near the railroad station. The Germans forced the Jews to build an eight-foot fence with barbed wire on top around the ghetto. In the ghetto, multiple families were crowded together into small houses, and food was scarce. The Germans forced Berel and others to do manual labor. The Jews were allowed to leave the ghetto to work.

Many people passed Marcinkanze while traveling through the area. The Jewish community heard about the massacres in Eyshishok on Rosh Hashana, 1941, and Radun in May 1942, about the deportations to death camps and other atrocities committed by the Nazis. The Jews in the ghetto began preparing. A group in the ghetto started to get guns and hide them outside the ghetto, preparing for an uprising. Some dug bunkers, hidden under the floor. Berel’s father prepared a pair of boots and a gold coin for each child, just in case.

On November 2, 1942, a train of cattle cars arrived outside of the ghetto. The Germans told the Jews they were being taken to work camps to gather near the train cars, to take a warm coat, and what they could carry. The Jews assembled on a small field inside the ghetto, across from the railroad cars. There only were twelve Germans and Lithuanians guarding the ghetto because they did not expect any trouble with boarding the train.

When the 360 Jews gathered near the railroad tracks, and the Germans ordered them to board the train, the Judenrat leader, Aaron Kobrowski, shouted: “Run, don’t go on the train!” Kobrowski told Berel and three others to attack the German guard standing just inside the ghetto’s gate, making Berel and his friends key players in the uprising. The guard saw them coming, stepped back, and started spraying machine-gun fire into the ghetto. The Jews ran in all directions, confusing the guards. Berel ran to his injured father, who said: “Please, go and see what you can do. I won’t make it much farther.” In despair, but knowing his father’s physical limitations from WWI injuries, Berel ran toward the fence.

Failing to break through the fence, Berel began to climb over. At that moment, a German soldier aimed his machine gun at him. Berel’s friend jumped on the soldier’s neck and subdued him, allowing Berel to escape to the nearby forest.

During the liquidation of the ghetto, Zelda was hiding alone in a small space above the fireplace that her father had prepared, just in case. She could hear the commotion of gunshots and screams. Much later that night, when things were quiet, Zelda left her hiding place and escaped into the forest, going to the family’s prearranged meeting place.

The next day, the Germans went house to house in the ghetto, killing the Jews wherever they found them. When the Germans found Jewish families hiding in bunkers, they tossed in grenades killing everyone inside at once.

The Marcinkanze uprising was unique in that not a single person boarded the German trains for transport to the concentration camps. Because the Nazi massacre was in town and in broad daylight, the locals could not deny the mass murder, unlike when Jews were taken away in cattle cars to an unknown destination. The peasants, farmers, and townspeople had to face reality, and this explains why some of the local farmers allowed the Jews hiding in the forest to take food.

Zelig had been shot in the massacre and pretended to be one of the dead, fooling the Germans looking for survivors. A farmer gave him refuge until he could get to the forest on his own. Zelig got to the forest, and all the siblings met as planned, hiding at a friendly Gentile’s farm. Zelig then became part of a family group.

The Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators regularly searched the forest to eliminate Jews who had escaped. Shmuel was captured by the Lithuanians who tied a rope around him and pulled him behind a horse, torturing him, marching him barefoot to the German headquarters in the town of Sobakinze where the Nazis murdered him.

One night, Berel, with his siblings Zelda, Noach, and Esther, and other survivors, sat around a fire to dry their wet clothes. Lithuanian Lieutenant Vincas Likauskas saw them and reported them to the German police, who surrounded the small group and opened fire. Noach and Esther, sleeping by the fire, were killed during that ambush. Zelda ran into the woods with an armed German soldier chasing her. She ran and ran, and when she looked back, the German soldier had stopped following her.

After losing his father and three siblings, Berel knew that he had nothing left to lose; his destiny was to live and fight. Berel used the gold coin his father gave him to buy a machine gun with a missing part; he re-built the part, repaired the machine gun, and became a machine gun operator. The fiercest group he could find to join was a group of Red partisans. He changed his name from Berel to Boris (a Russian name) and joined the group in the marshy forests of Nacha and Belarusshkaya. He did what was needed, serving as a scout, a fighter, an explosives expert, and a medic if needed. Zelda adopted the Russian name, Zina, and joined her brother in the Red partisans, performing mainly domestic duties for the group. Boris was determined that his sister be allowed to join the group so that he could protect her. The Novicks were among the very few Jews in their unit.

The partisans went on missions to sabotage German communications and supply convoys and to destroy German railroad tracks and bridges. They fought both the Germans and the lawless groups roaming the forest. They protected the family groups. Their leader was killed while fighting roaming criminals. Stankiewicz, a former captain in the Russian Army, took over leadership and ran the group with military discipline. They continued doing missions targeting German railroad tracks, bridges, and supply convoys while fighting the Germans and protecting the family groups.

Life in the partisans was challenging, as the fighters did not have basic necessities. They made make-shift boots from rags or gunny sacks and pieces of leather. Obtaining food was a constant struggle, and the partisans regularly went on missions to gather food from local farmers.

During one mission in 1943, Boris and the partisans were resting at an unoccupied farmhouse. Boris was outside in the morning when he noticed German soldiers approaching. Armed with only his pistol, he quietly ran inside to alert the others. Boris then grabbed his machine gun and opened fire through the windows, going from window to window to provide cover while the others escaped and made it appear as if the house was full of fighters. As the partisans and Germans exchanged fire, Boris was shot below his knee but kept fighting.

Stankeiwicz’s group eventually joined with the Davidov detachment. They continued to disrupt railroad and bridge transportation systems, convoys and fight, defend others and defeat the Germans one mission at a time.

Another time, Boris and a fellow partisan, Avrom Asner, captured a man named Gontsheruk, notorious for spying and reporting the location of those Jews who lived in the forest. The Germans and their collaborators would ambush and kill anyone found. Avrom caught Gontsheruk off guard, and they seized him. While Avrom held a pistol to Gontsheruk’s head, Boris searched him and tied his hands. They then delivered Gontsheruk to the partisan headquarters, where he was interrogated and executed.

On another mission, the partisans discovered unexploded bombs in the swamps. Boris helped disarm the live bombs and create new explosives. Taking the explosives to a railroad track on a hillside, they blew up a German supply train en route to Russia.

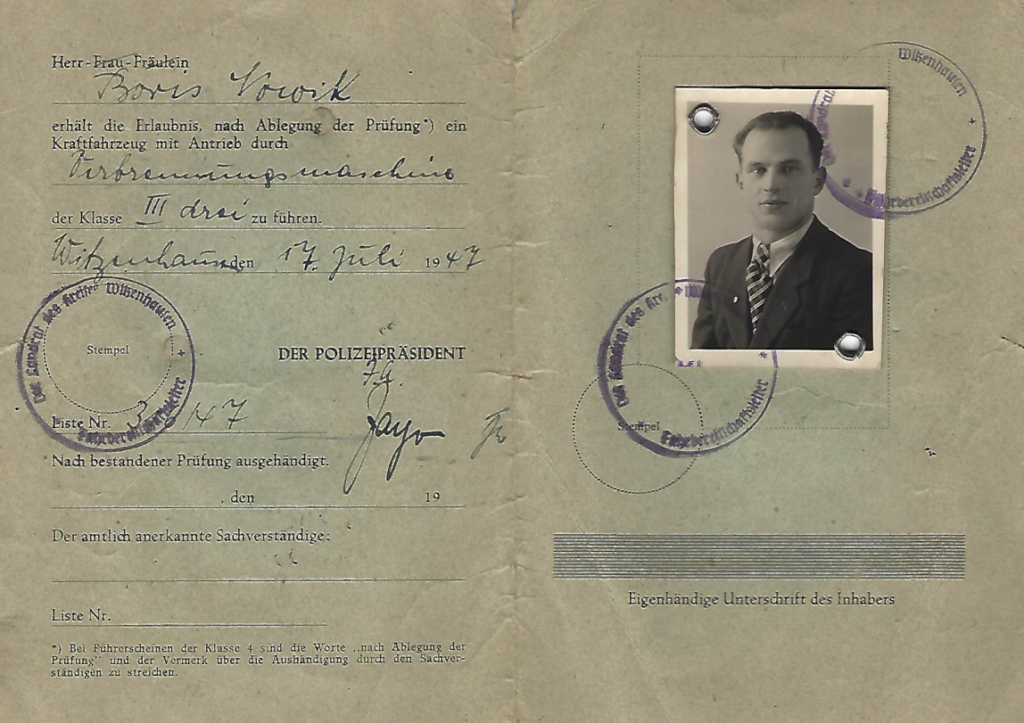

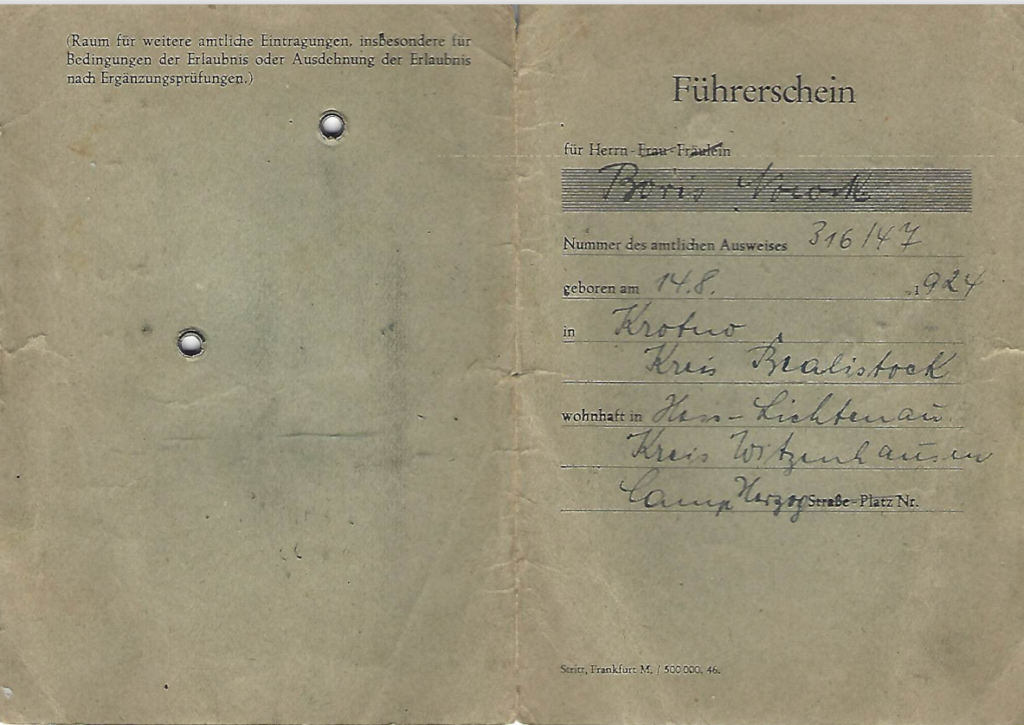

After three years with the partisans, they were liberated by the Russian Army. Boris, Zina, and Zelig returned home with no options for the future. They made their way through Poland and on to Germany. Boris and Zelig went to Camp Herzog Hessisch-Lichtenau, a Displaced Persons camp in Kassel, Germany, where they both worked as UNRRA police for the camp. Boris was the assistant police chief. Boris met Betty (Bryna Mekel) from the neighboring Camp Goldcup. They were married on July 6, 1948. Zelig also met and married his wife, Miriam (Yagodnik), in the camp and immigrated to Israel, where they had their son, Yehuda. Zina went with a different group to a Displaced Persons camp in Italy, where she met and married her husband, Jack Freeman (Yitzchak Kwaitkowsky), and had their daughter, Deborah.

In 1949, Boris and Betty were sponsored by Boris’s uncle, Alex Rose, a tailor who lived in Wichita, Kansas. Uncle Alex also sponsored Zina and her family from their DP camp in Italy. They all were able to immigrate under the requirements of the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. They settled in Wichita, Kansas, where Uncle Alex had a job for Boris.

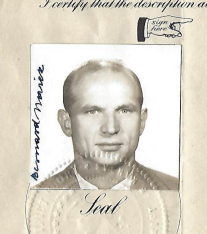

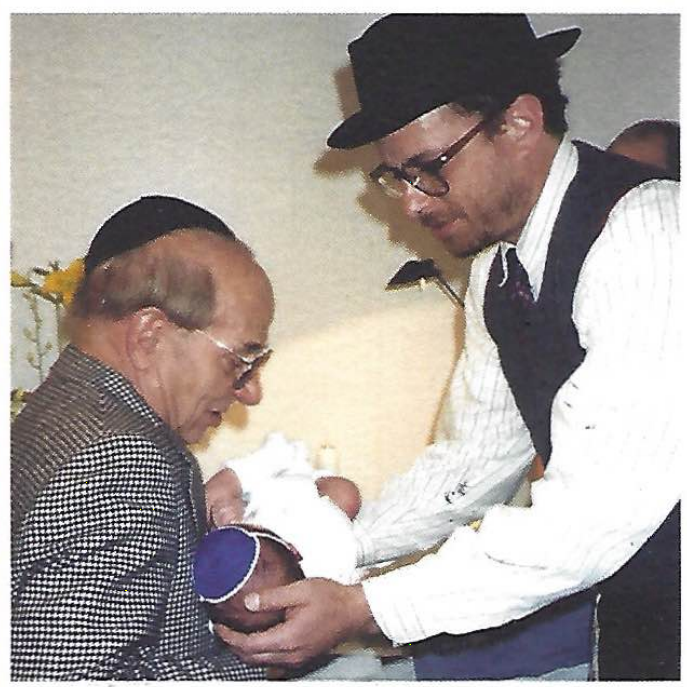

However, because of Boris’s background as a blacksmith, he worked for various metal companies while learning English. Boris started using the American name, Bernard or “Bernie.” He soon bought a truck and started his own business buying scrap metal and preparing it for recycling. As the business grew, Betty worked alongside him, doing paperwork and bookkeeping. Their business ultimately became one of the largest recyclers in Wichita. He helped many other immigrants and minorities learn the trade and start their own businesses. Bernie and Betty had two children, Jay (Yehuda Eliezer ben Dov) and Charlene (Chaya Sarah Eshe), along with four grandsons and three great-grandchildren.

Bernie and Betty were active in their synagogue, the Ahavath Achim Hebrew Congregation. Bernie served as Chairman of the Jewish Cemetery Committee for many years, and he served on the Synagogue’s Board. Bernie and Betty were active in the Midwest Jewish Federation, B’nai B’rith Hadassah, and other philanthropic organizations.

Bernie shared his experiences of the Holocaust to educate future generations, speaking at schools and churches. He and Zina both shared their experiences in interviews with History Professor Donald Douglas. The play Forest Children was written about Bernie and Zina by Professor Douglas and performed at universities and churches in Wichita.

On September 28, 2001, Bernie passed away after living a fulfilling, inspiring, and courageous life.