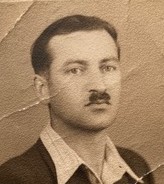

Born in 1922, in Novogrudok, Poland, Sonya Gorodynski, was the oldest of five children born to Abraham and Tamara Gorodynski. Her father lovingly called her Sonyaleh.

An excellent student, Sonya had planned to attend Medical School in Smolensk, Russia, the year that the Soviets invaded, but she had to adjust her plan, and she ended up studying French and Latin at the University in Bialystok.

Although the Soviets deported many Jews to Siberia, the Gorodinskys were left alone because of Sonya’s father’s standing in the community. Life changed drastically when the Nazis occupied Poland. They systematically murdered most of the town’s Jewish population, including Sonya’s youngest brother and grandparents. On June 24, 1941, Sonya was the only one in her home on Pilsudski Street, when she heard a bomb explode nearby. Fleeing the house, she watched as a second bomb hit, and her home was reduced to broken splinters and burning embers.

By May of 1943, only 500 Jews remained in Novogrudok – mostly skilled laborers and their families. The Nazis confined them to the city’s courthouse, where they lived in squalid conditions in what became a makeshift ghetto. On May 7th, the Nazis conducted another massacre, reducing the ghetto population by half. Sonya’s mother and eleven-year-old sister were killed.

Following this massacre, the remaining 250 Jews began plotting their escape. The initial plan to storm the courthouse gates fell through when the Nazis discovered their plot. Instead, the escapees decided to dig a tunnel underneath the ghetto through to the woods; a slow, stealthy escape through a hidden tunnel would give the sick and the elderly enough time to get out.

The work was difficult and dangerous. The excess earth had to be disposed of, and the summer rains threatened to collapse the tunnel. To avoid suspicious dirt stains, those digging wore burlap sacks – or dug naked. Even in these dire conditions, Sonya found a ray of hope when she befriended and fell in love with Aaron Oshman during the time they spent digging together. Just a month before the escape, Sonya’s father was transferred to another ghetto, along with a handful of skilled workers. She never saw him again.

The Novogrudok tunnel escape finally happened on a rainy September night. About seventy of the escapees, including two of Sonya’s cousins and the tunnel’s mastermind, were killed when they became disoriented and accidentally ran back towards the ghetto. They were shot by the guards, who mistook them for ambushing partisans.

Sonya hid in a little ditch and then went through a cornfield where the leaves and the stalks were quite high. She knocked on the window of a house in the woods, and an old man came to the door and said, “I know who you are. I want to help you.” She eventually made it to the relative safety of the famed Bielski partisan camp. There, she was reunited with her one surviving brother Shaul, and with Aaron Oshman.

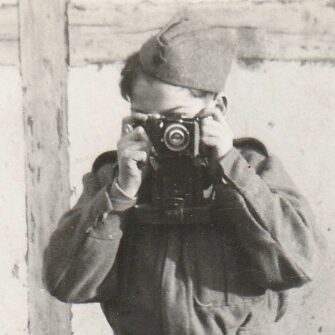

As a member of the Bielski Brigade, Sonya performed many essential duties and was instrumental in safeguarding the camp’s population by standing sentry. One day, she spotted a group of haggard looking men approaching the camp. When she asked where they had come from, they told her they had recently fled Koldichevo, the camp where Sonya’s father had been imprisoned.

She learned that her father had escaped but was later captured and killed. They relayed to Sonya his dying warning to his murderers, “You will kill me today, but I have a son and daughter, and they will survive and tell what happened here.”

Sonya and Aaron Oshman stayed with the Bielski Brigade throughout the war and were married in the Naliboki forest towards the end of 1943. They fashioned their wedding bands from a gold filling given to them by one of their fellow partisans.

After the war ended, Sonya and Aaron traveled across Europe, finally making it to a Displaced Persons camp in Italy, where they were reunited with many of their fellow Bielski partisans. Their first child, Matthew, was born in the DP camp before they immigrated to the United States and settled in Brooklyn, New York.

As Sonya’s father predicted, she dedicated her life to sharing her story and to teaching people about the resistance of the Jewish partisans. She traveled extensively and spoke in schools, synagogues, and community centers across the country.

When sharing her story with others, she always said, “My name is Sonya Oshman, and I wish to speak of my father. From 30,000 Jews [in the region], perhaps only 150 survived, and from the Gorodinsky family, I am now the only living member. But I want to keep my father’s promise, so I am standing here and fulfilling the last wish of my dad. I am telling you a little fragment of my story. In this way, I hope my father’s life will be one of the lives remembered.”

About her escape through the tunnel, she said, “We wanted to show the world that Jews are not sheep that go to the slaughter. We decided whoever will make it will make it and whoever would not would not. It was better to die this way than the other way. And maybe someone will survive to tell the world what happened. We were anxious to get out as fast as we could because we had death waiting for us. We just wanted to get out. We wanted our lives.”

Sonya and Aaron Oshman were married for 56 years and had two sons, Matthew and Theodore, and four grandchildren, Charles, Max, Michael, and Sophie. Sonya passed away on March 2, 2012, leaving us this important reminder: “Hope lives when people remember. You must spread the message that hate is a failure and love is a success.”