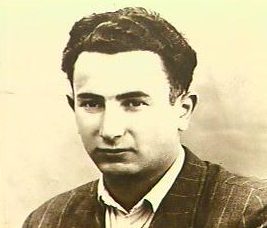

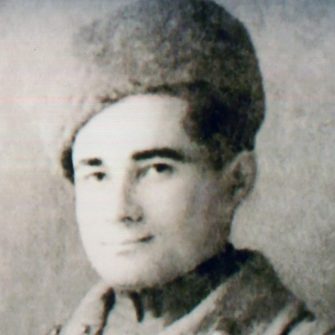

David Figman was born on December 24, 1926, in Warsaw, Poland. He lived with his parents, Shmuel Wolff and Masha, along with four siblings: Faye, Jack, Malka, and Yosele. He grew up in a traditional Jewish home and attended public school and a cheder. His father was a tailor who ran his business in the family home. Growing up, David had many Gentile friends and enjoyed going to the movies, playing games, and reading books.

In September 1939, Germany attacked Poland, catapulting the world into war. At the outbreak of the war, David’s older sister and brother fled to Russia. Warsaw was heavily bombed and while David’s home was spared from destruction, buildings around it were obliterated. Anti-Jewish laws were soon enacted in Warsaw as the Germans marched into Poland’s capital. One day, when David was delivering a suit to his uncle from his father’s shop, he was stopped by German soldiers. They immediately took him to a locomotive factory, where he was forced to work for the Germans.

The Warsaw Ghetto was established in October 1940 and sealed off from the world in November 1940. Nearly half a million Polish Jews were enclosed into an area of just 2.4 percent of the city and surrounded by a 10-foot brick wall. Between 1940 and mid-1942, an estimated 83,000 Jews died of starvation and disease. David continued working in the factory, bringing bread home to sustain his family. His younger brother smuggled food from the Polish side, risking his life in the process.

The Germans began liquidating the ghetto in July 1942 and deporting Jews to Treblinka Concentration Camp. David’s mother, younger sister, and brother were all taken to their deaths. David and his father were spared because of their work papers. Around this time, David became involved with the Polish underground that was forming in the locomotive factory, as well as the Jewish resistance in the ghetto. He was given false papers and had a safe house with a Gentile family on the “Aryan side” of Warsaw.

David frequently returned to the ghetto to be with his father who worked as a tailor in the Schultz factory. One day, David was coming back into the ghetto from work when he was stopped by an SS soldier who demanded to know what was in David’s backpack. The soldier frisked him and discovered bread and money. David was ordered to stand in front of the brick wall. Knowing what was coming, David broke into a run, dodging bullets as the soldier shot at him from behind.

After deporting over 300,000 Jews to death camps in two months, the Nazis planned to liquidate the entire ghetto in April 1943 as a birthday gift to Adolf Hitler. David was preparing to have a Passover seder with his father and cousins when his father suddenly remembered that he had left something at the factory. That was the last time David saw his father.

On April 19, 1943, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began. Over 700 young Jewish fighters fought the German Army for nearly a month. David gathered with other friends and fighters to receive orders from the commander of the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB, Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa), Mordechai Anielewicz. The fighters filled their glass bottles with gasoline from a large barrel and said their goodbyes to each other as they took their positions against the German Army. David was positioned in a third-story window near Mila Street, where he threw Molotov bombs on incoming SS tanks. The Nazis were afraid to enter the ghetto as they were met with fierce resistance.

However, as the Uprising continued, the German and Ukrainian SS soldiers entered the ghetto and poured gasoline on buildings, setting the ghetto on fire. David found shelter in a bunker with other fighters. After a few weeks, they had dug a hole into the sewers. As David and his fellow fighters maneuvered through the sewers, they were met with gunfire at each opening they tried to emerge from. They were stuck. Eventually, David managed to escape and was chased by the Polish Police and the German SS. He jumped from a second-floor building, miraculously emerging with only a strained leg. He went back into a bunker with the remaining fighters until the Nazis began gassing the Jews out of their hiding places. David and his comrades had no choice but to climb out of the bunkers.

David was taken by the Nazis past the burning remains of the ghetto toward the Umschlagplatz, the deportation point from which thousands of Jews had already been sent to extermination camps. The following day, David was forced into a cattle car along with over a hundred young Jews who had survived the Uprising.

They were taken to Treblinka Concentration Camp. David peered through the cattle car window, spotting a line of trains in front of them from all over Europe. As they waited to see what would happen to them, people began stretching their hands through the small windows, an action that was quickly met with machine gunfire. It was finally decided that David’s train would turn around and be sent to Lublin because the young people could be used for slave labor. As the train pulled away, David evaded a death camp in which there were only 70 survivors.

Majdanek Concentration Camp was only six miles from Lublin. As the train arrived at the work camp, a fellow underground member recognized David. The man instructed David to lie about his age and say he was sixteen and a skilled worker, knowing that if David didn’t he would surely be murdered in Majdanek. David took the man’s advice, and his life was spared. David was sent to the Budzyn forced labor camp, where he worked in an airplane factory for the Heinkel-Flugzeugfabrik firm.

As the war progressed, the German Wehrmacht brought in trucks and tanks to be fixed by the slave laborers. One day, David became ill with a fever. A German soldier, whose truck David had been working on, brought him aspirin and hid him behind the truck, where David could rest. The soldier gave him a can of soup and bread, which David shared with his friends. He was the only German who helped David during the war.

At the end of 1943, the Russian Army was approaching, and David was ordered to dig anti-trench ditches. One day, a group of two dozen SS soldiers with machine guns approached David’s group as they were working. “We’ve come to kill all of you,” they said. “These trenches are for you.” However, because David and his fellow inmates worked for the factory, they were spared and sent to a forced labor camp in Mielec, Poland, not far from Krakow, where they worked in another airplane factory.

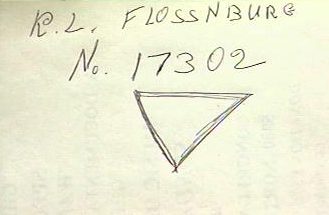

David was then sent to Flossenbürg Concentration Camp in Germany, where he met Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a well-known Christian theologian who was imprisoned and later hanged in the camp. Before long, David was sent to Holleischen, a subcamp of Flossenbürg, and worked in an ammunition factory in the bitter winter cold. As the Russians were approaching, David was put on a train and sent back to Flossenbürg and forced to work in a stone quarry on starvation level rations. David could see the Allies nearing as American planes dove through the sky.

In April 1945, the Nazis forced the Jews onto trains. They were strafed by American planes that didn’t realize they were prisoners. Over a hundred prisoners were killed in the shootings before the planes understood they were not German soldiers. David and those remaining were sent on a forced march in the pouring rain. They didn’t eat for days, and those who could not walk were immediately shot.

David’s group was taken to a large barn. He looked through the wooden beams, spotting other groups of Jews approaching the nearby forests. Machine gun fire echoed throughout the night, and David’s group was the only one that survived the mass shootings.

The Germans finally fled as the Allies approached. On April 23, 1945, David emerged from the barn and saw tanks rolling up the dirt road carrying his liberators, the United States Army. David remembered feeling as though he were “born again” on the day of liberation. He was now able to begin a new life after losing everything in the Holocaust.

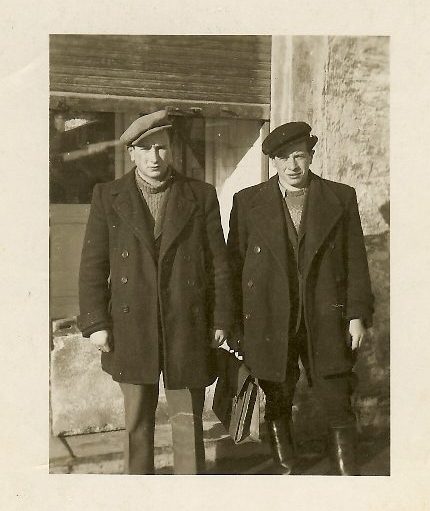

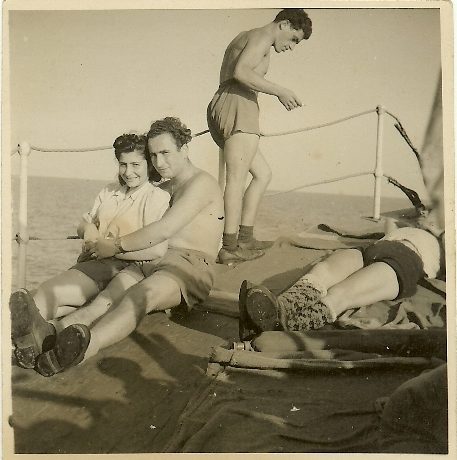

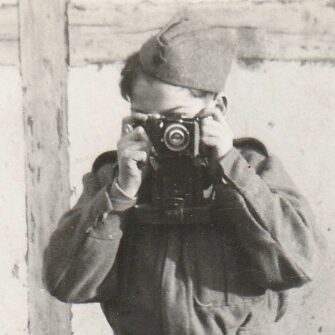

David slowly recuperated his strength and stayed in Germany, not wishing to return to blood-stained Poland. He joined the Haganah in 1948 and trained to be a soldier in Marseilles, France before boarding a fishing boat bound for Israel. The training, coupled with his experience of combat in the ghetto, prepared him to fight in the Israeli War of Independence.

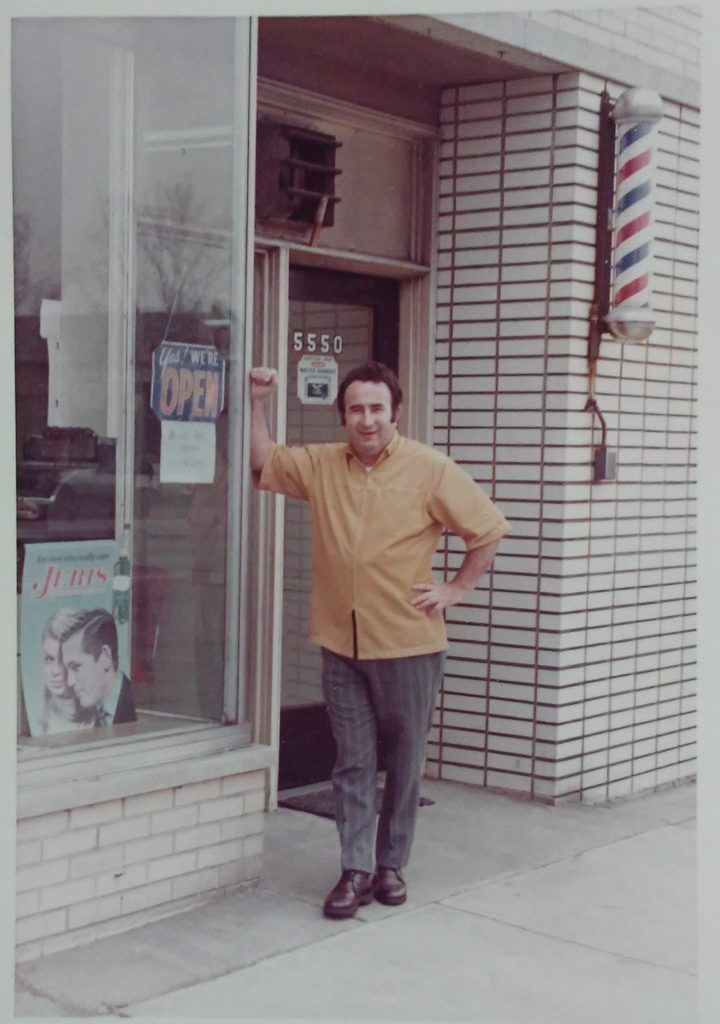

David was a mechanic in the Israeli Army and worked in a steel factory and as a barber in Israel before immigrating to the United States in 1959 to be near his surviving older sister and brother. At first, David worked as a barber in New York before moving to Chicago where his brother was residing. A friend of David’s soon introduced him to his neighbor, Myrtle. She was born in 1923 and was a native of Chicago. They were married in 1961. They had a good life together in Chicago, where they raised three daughters and had five grandchildren.

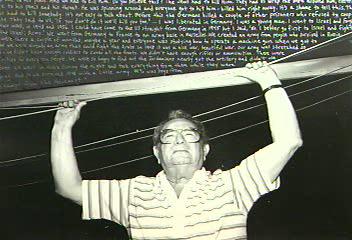

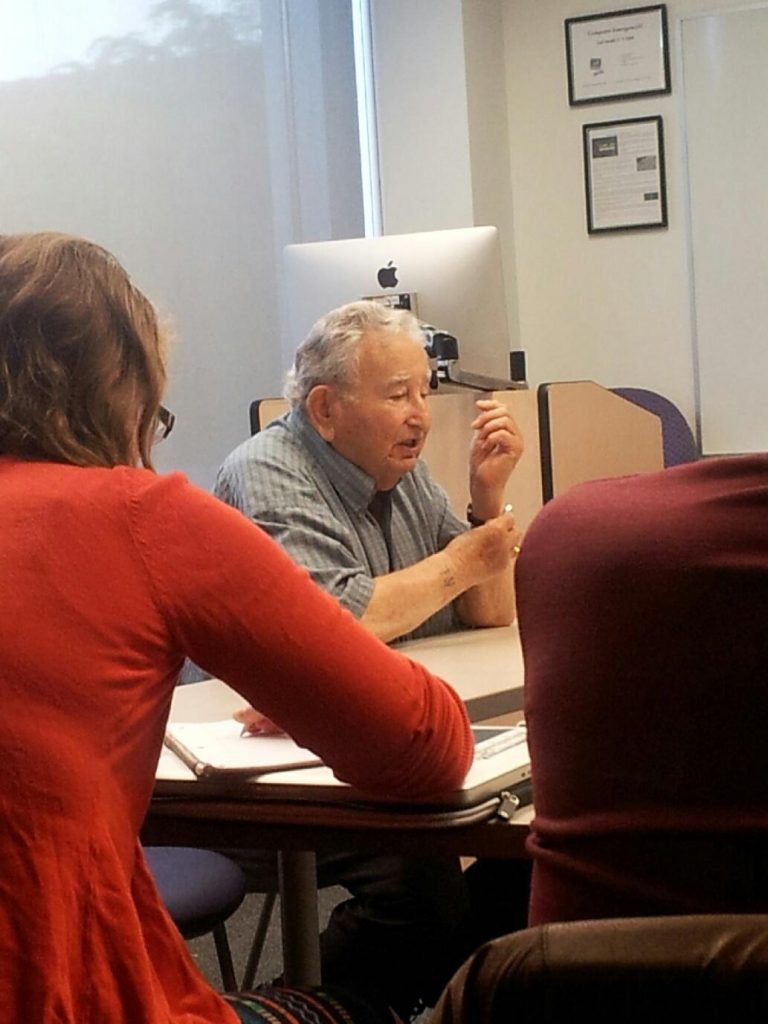

David and Myrtle were founding members of the Illinois Holocaust Memorial Foundation (the precursor to the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Educational Center) and were very active in the organization. The Illinois Holocaust Memorial Foundation was instrumental in getting a state mandate passed in Illinois requiring the Holocaust to be taught in schools. David spoke about his experiences to hundreds of students for many years.

Despite the pain and loss that David experienced during the war, he emerged as a resilient individual. David passed away in 2016.