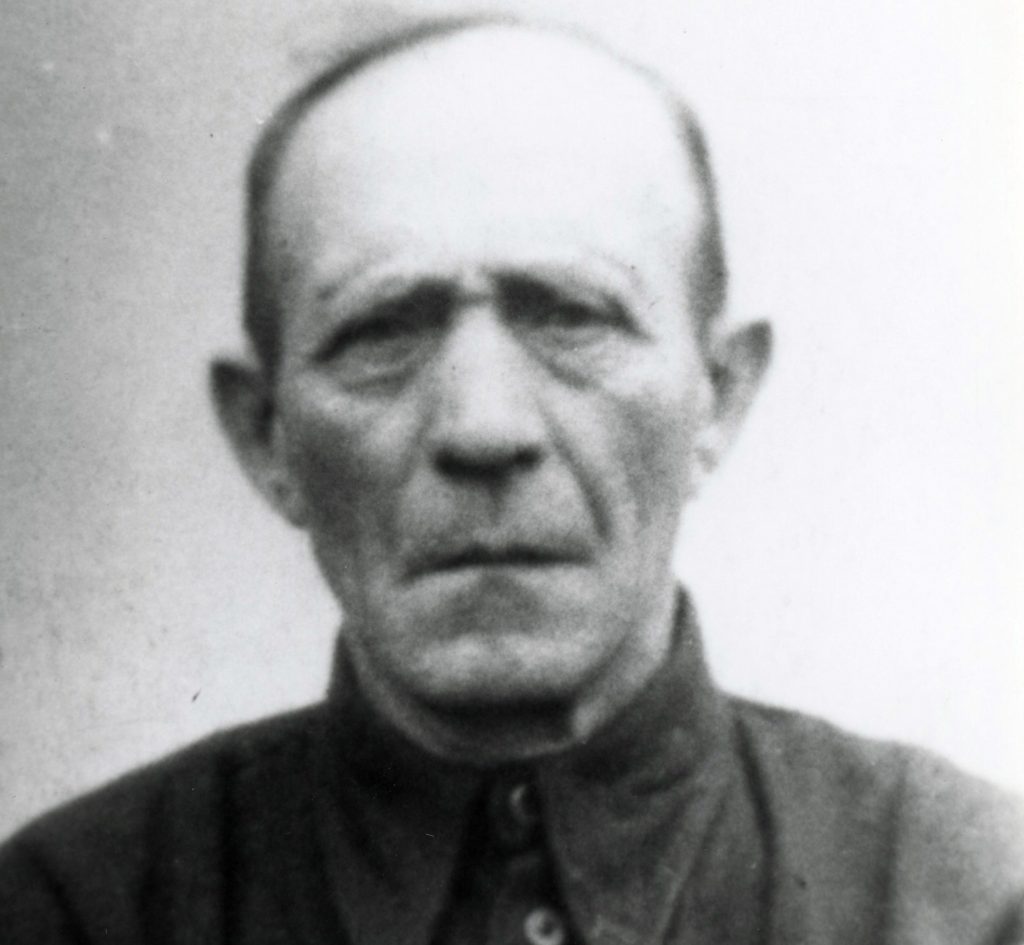

Samuel Boymel was born on May 5, 1923, in the Volhynia province of Turisk, Ukraine. He lived with his mother, Rochel, and three sisters: Raiszel, Malca, and Chaisa. Sam’s father, Zelig, was a tailor who died when Sam was only three years old. After Zelig’s death, the family became poor overnight. Rochel took in laundry and cleaned homes to keep food on the table.

Turisk was principally a Jewish community. Sam attended Hebrew school and enjoyed his studies, but his mother could not afford to buy the needed books. Sam spent much time with his grandmother, a businesswoman in the finest sense of the word. He helped load and distribute goods she bought from the local farmers, tended to her four horses, and made sure her wagon wheels were properly greased. Sam was a member of the Bund, and they were rivals with the Zionist, Baytar, and Communist groups. This rivalry led to stiff competition in soccer games.

On September 1, 1939, Sam’s life drastically changed as Germany invaded Poland. According to the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression agreement, the whole of Volhynia, including Turisk, was annexed by the Soviet Union. However, in June 1941, the Germans broke the agreement and invaded Russia. On June 28, 1941, the German Army marched into Turisk and immediately enacted anti-Jewish laws. Every Jew was required to wear a Star of David on their clothing, and a ghetto was created. The Germans mobilized a local Ukrainian police force to aid them in enforcing these measures, while non-disabled male Jews were required to report daily to the railroad yards for forced labor.

On Sunday, August 23, 1942, when Sam was seventeen years old, the Germans and Poles attempted to extort a ransom from the 6,000 Jews of Turisk. The Jews were forced to gather in the center of town. A ransom demand was made, but they could not come up with the amount the Poles demanded. At that time, the Germans also circulated a lie that the Jews of Turisk would be relocated to work in the city of Kovel. Sam clung to this promise with one suitcase in hand as he stood in the town square with his extended family: mother, sisters, brother-in-law, and two-month-old nephew.

However, the Germans had other plans. On the outskirts of town, the Wainer Brick Factory had been an excavation site for clay. It was deep and wide. The Germans decided this site was an appropriate place for the “final solution.” Believing they were walking to Kovel, Sam, his family, and the Jewish residents of Turisk began the arduous, grueling walk on the cobblestone road under the watchful eyes of local Ukrainian police, militia, and German soldiers.

As they arrived on the outskirts of town, they were turned uphill to a dirt path toward the Wainer Brick Factory. Fear, screaming, and panic set in as the Jews of Tursik were herded toward their ultimate fate. As they neared the top of the hill, Sam’s mother told him: “Get some long pants, take my sweater. I don’t want you to catch a cold. Run my child.” Sam instinctively obeyed and fled to the Rostov Forrest towards the town of Rostov, nine miles away. His sister, Raiszel, followed but was killed as she ran. Sam looked over his shoulder as a bullet hit her back. He kept running, hearing his mother’s wailing scream. On that day, 6,000 Jews from Tursik and another 6,500 from the surrounding villages, shtetls, and towns were executed and buried in mass graves in the Wainer Brick Factory excavation site.

Sam fled the mass executions, running nearly all night until he reached Rostov, where he sought shelter with a local land owner, Petrivna (Petrov) Tokavska. The next evening, Sam’s uncle, Label Opliner, arrived at Tokavska’s home and sought shelter. He informed Sam that everyone in their family had been killed, his own wife and children included.

Label struck a deal with Tokavska. Tokavska needed windows installed in his home, and Label, a carpenter by trade, agreed to do the work in exchange for food and shelter. Sam and Label hid under the pig pen, which was covered by wooden boards and straw. During the day, they installed the windows; at night, they slept and ate in their hole in the ground. They stayed there for two months.

In early November 1942, the Ukrainian militia surrounded Petrov Tokavska’s barn. They suspected him of hiding Jews and began chanting, “Jews come out.” At this time, Sam and his uncle were hiding in the loft. Label peered out of the wooden slats of the barn and recognized a few of the men below. He urged Sam to go with him and talk to these men. Sam was frightened and didn’t think it was a good idea. They sounded angry. Label told Sam to stay put, confident he could deal with them. Minutes seemed like hours until Sam heard a gunshot penetrate the air. He peeked between the barn siding and saw his uncle lying dead. Sam leaped through the back window of the loft and fled into the forest.

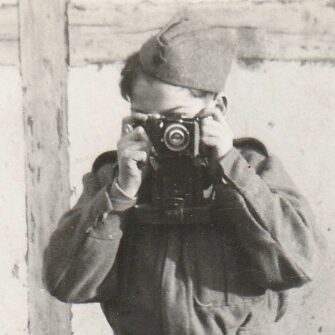

While in the forest, Sam met a Jewish partisan group with whom he served for the next eighteen months. He spent the next year and a half sabotaging German railroads and communications to disrupt the flow of supplies to the front. During one attempt to blow up a railway line in early 1944, Sam was wounded and sent to a Russian medical unit in Moscow to be treated for his wounds.

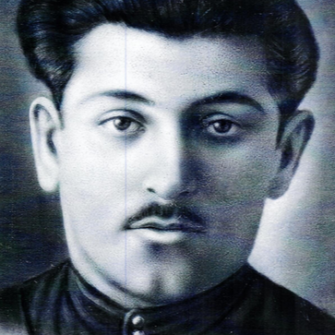

As Sam returned to the front in March 1944, he wandered into Chelm, Poland. He met an older Jewish gentleman and inquired if any young Jewish women were in the town. The stranger pointed him to a two-story house. Sam knocked on the door, and Rachel Czerkiewicz (born on January 1, 1923) answered the door. Rachel initially refused to date Sam, thinking he was a gentile because he didn’t look Jewish. However, Sam persisted, and on June 22, 1944, they got married. Sam and Rachel stayed in Chelm until the war ended.

After the Russians liberated the East in 1944, the couple migrated from Chelm to their hometowns and discovered that no one from their families had survived the Holocaust. They decided to seek refuge in the Western zone of Germany. On the way, Sam was arrested by a Russian captain for his capitalist enterprise of selling flints to light cigarettes. After his arrest, Sam was interrogated and went under the name “Alexander Sonovich.” The captain knew he was lying. He told Sam his father’s name was Zelig, and his last name was Boymel. The captain was also a Jew from Turisk. He took Sam’s money and flints but let him go with a warning: Leave Soviet-controlled Europe if he knew what was good for him.

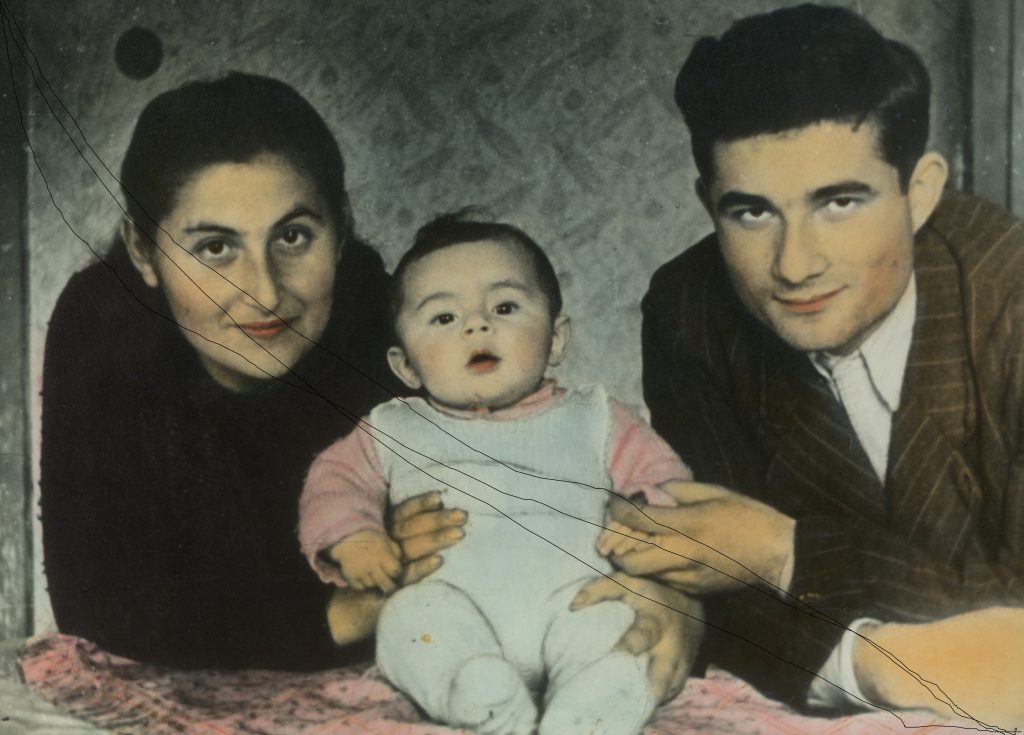

Sam and Rachel lived outside Munich in Foehrenwald, Germany, in Wolfratshausen, a Displaced Persons camp. They lived in a military barrack-style home on Washington Street. There was no work to be had, but Sam bootlegged vodka, which he sold to the American GIs stationed nearby to make a living. Sam and Rachel’s son, Steven, was born in 1946 in the camp infirmary.

Sam’s aunt lived in the United States and sponsored Sam, Rachel, and Steven through the Marshall Plan. This American initiative provided economic aid to postwar Europe. On May 4, 1949, they immigrated to the United States and settled in Cincinnati, Ohio.

After Sam, Rachel, and Steven arrived in Cincinnati, Sam’s first job was helping to build the Chofetz Chaim Hebrew Day School. After a month, his uncle got him a job as a butcher at Oscherwitz Kosher Sausage Company on West Sixth Street, which later became Best Kosher Food Company. The couple had two more children: Patsy in 1951 and Faye in 1956. Sam left Oscherwitz and opened Boymel’s Kosher Meat Market on Section Road in Cincinnati. 1967, he purchased the Garden Manor Nursing Home in Middletown, Ohio. Over the next four decades, his single nursing home grew to five homes.

In 2000, Sam returned to Tursik. Sam hired an architect and engineer to build a cemetery on the site where his mother, sisters, brother-in-law, nephew, and thousands of other Jews had been murdered in a mass grave. In the middle of the cemetery stands a tall headstone written in Russian, English, Hebrew, and Polish, describing who is buried there.

During his visit, Sam found a small bone in the cemetery that must have risen after the drizzle the day before. He put the bone in his pocket. “This could be my mother’s or sister’s bone. I’m taking this bone back to Cincinnati and will bury it in an Orthodox Cemetery,” he told his son. When they returned to Cincinnati, the family had a funeral for the bone, and the entire Orthodox Community attended.

Sam hoped to meet Petrov Tokavska again, the man who had saved his life, but discovered that he had passed away. In a miraculous turn of events, Sam had the opportunity to meet and thank Petrov’s daughter, Nina, while in Tursik.

Sam openly shared his war experiences with his three children and twelve grandchildren. He continually reminded his family: “Don’t forget where you came from.” Sam was deeply involved in his community, serving as the Israel Bonds Chairman in Cincinnati for 20 years. He built the Cincinnati Hebrew Day School, the Sam and Rachel Boymel Campus, a synagogue at the Rockwern Hebrew School, and endowed a Hospital and Adoption Center in Israel. He and his son were also instrumental in building a tennis center at Gvat Katz Nelson in Israel.

Sam passed away on January 19, 2018.