This report is based on a chapter of Betty Brodsky Cohen’s upcoming book, “The Tunnel People,” which tells the personal stories of the Novogrudok tunnel escapees.

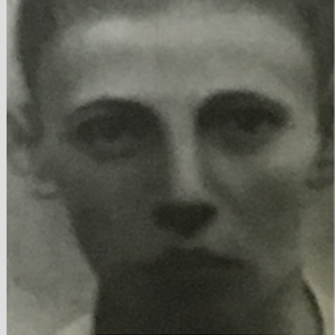

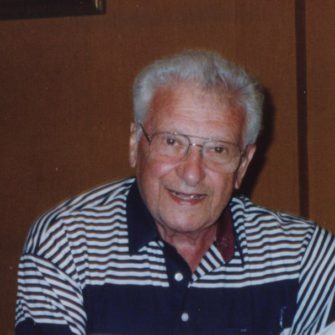

Shlomo Ryback was born on March 12, 1914, in Radun, Poland. He lived with his parents, Gisia and Ephraim, and four siblings: Shimon, Yehuda, Velvel, and Yentl. At the age of four, Shlomo suffered the first of many losses when his mother died in the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. Shlomo was raised by his father who was a beekeeper.

After graduating from a teachers’ seminary in Vilna in the early 1930s, Shlomo began an illustrious career as a Hebrew teacher in the small Belorussian town of Turetz. In 1938, Shlomo was appointed principal of the Novogrudok’s Tushia School, a private Jewish religious school on Kostchelna Gass (Church Street).

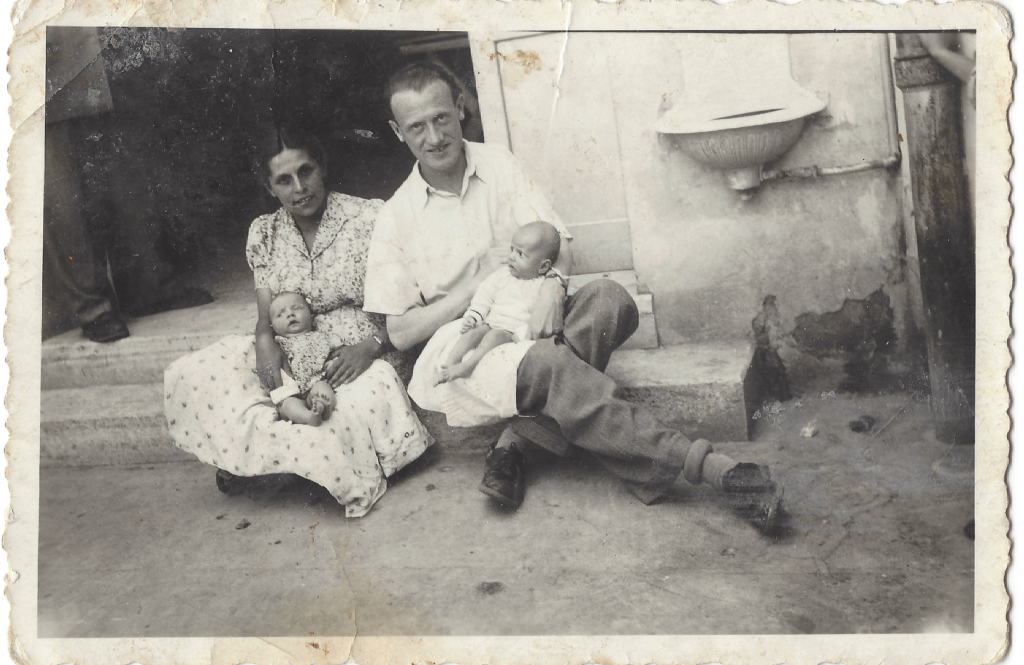

On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union annexed Novogrudok in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Germany which partitioned Poland between these two countries. As Novogrudok fell under Soviet control, Shlomo was forced to adapt his curriculum to reflect Communist ideology. During this time of upheaval, Shlomo married Chana Iwinietcka who was born on March 31, 1913, in Novogrudok, Poland. In 1941, Shlomo and Chana had a son who they named Ephraim.

In June of that year, Germany broke their pact with Russia and invaded the Soviet Union. On July 4th, 1941, the German Army occupied Novogrudok. In 1942, while the young family was interned in the Pereseka Ghetto. Shlomo was sent on forced work detail when word came that the Germans were preparing an aktion to slaughter the children in the ghetto. Having witnessed the brutality of previous aktions, Chana and Shlomo knew that two-year-old Ephraim would be tortured and slaughtered by the Germans. In an act of desperation, Chana and her sister, Mirke, put their children to sleep forever with injections. Chana’s agonizing decision tormented the couple for the rest of their lives, even while rebuilding their family after the war.

In May 1943 while in the Novogrudok Forced Labor Camp, Shlomo and Chana were among the 250 remaining Jews in the camp who decided to escape. In four months, they helped dig a tunnel underneath an inmate’s bed which led to a hillside outside the camp. They escaped on September 26, 1943, under a hail of gunfire. Shlomo and Chana risked their lives to save a man named Chaim Noah Leibowitz who had fallen into a hole upon their escape and was knee-deep in water. They grasped him by the arms and dragged him from the deadly trap before fleeing together into the nearby forest. Shlomo, Chana, and other escapees set out to reach the renowned Bielski partisans. Along the way, they stopped at the homes of sympathetic Polish farmers before eventually being picked up by a wagonful of Bielski partisans.

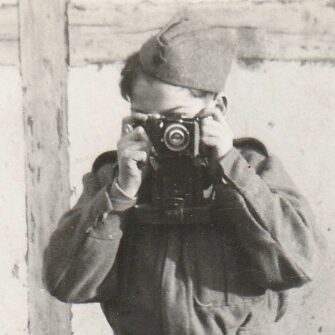

Shlomo and Chana joined the Bielski Brigade where Shlomo worked as an ambulance driver, transporting typhoid patients to the partisan hospital. He also taught young children and teenagers in the partisan forest school.

By the winter of 1943-44 another partisan unit, the Zhukov detachment was moving out of the Naliboki forest. Its commander requested that Tuvia Bielski accept several of his wounded and ill, as well as several women who were considered burdensome. In exchange for Tuvia’s acquiescence, the Bielski detachment was given food, cows, horses, kitchen tools, and lice-infested clothing. With the lice came a severe typhus epidemic, causing many infected partisans to be transferred to Dr. Hirsh, the physician who Chana was assisting during her time in the partisans. The task of transporting the ill to the increasingly overcrowded “hospital” huts several times daily fell to Shlomo in his horse and buggy.

After they were liberated by the Russians in 1944, Shlomo could not face the trauma of returning to schools bereft of Jewish children despite the request of the Russians to help reorganize schools after the war. Shlomo preferred to fight on the front with the Red Army. However, Chana managed to keep Shlomo out of the Red Army by finding him a job as a bookkeeper for the Novogrudok jail, the police station, and the fire station. Chana worked in the Russian Army infirmary as well as in the jail where, at risk to her own life, she was able to assist many Jewish prisoners. While trying to help fellow tunnel escapee Raya Kushner pass a message to her imprisoned father, Zeidel, Chana was taken in for questioning. Without Shlomo’s intervention, she could have been deported to Siberia.

Shlomo and Chana made their way to Lodz, Poland in 1945. Shlomo was asked by the “Bricha” underground organization to lead a group of stateless Jewish refugees attempting to illegally enter British-ruled Palestine (then closed to immigration). After journeying from Lodz to Bratislava, the group passed through Hungary, Austria, and Yugoslavia before finally arriving in Italy where they were to board a ship. There, in the central Italian town of Ascoli Piceno, Chana gave birth to twins on May 27, 1946. Tzipora (Sylvia) was named for the maternal grandmother she never knew, while her brother’s name Amitzur (Hymie), meaning “My nation is a Rock,” was perhaps chosen to commemorate the strength and very survival of his parents. Shlomo became a Vatican library employee in Castel Gandolfo during this period.

Chana ultimately opposed their original plan to immigrate to Israel for fear of the ongoing conflict in the region. On March 2, 1950, sponsored by Shlomo’s cousins who lived in Montreal, the family sailed for Canada aboard the SS Samaria.

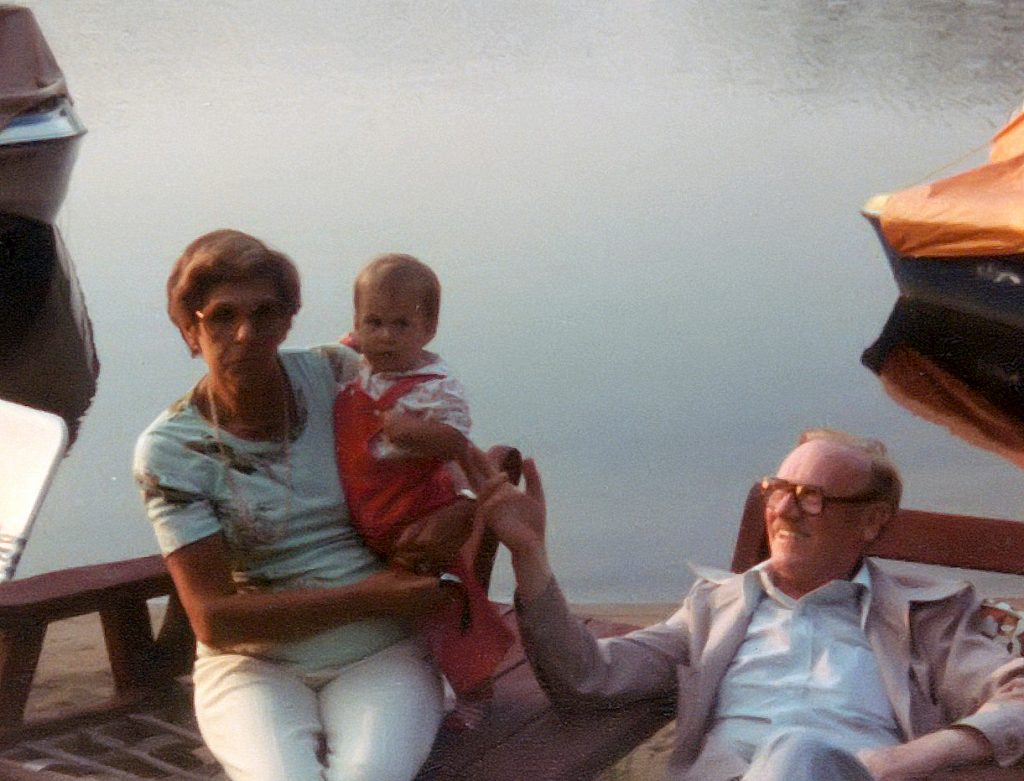

Although Ephraim’s tragic death cast a lifelong shadow over Shlomo and Chana, they rebuilt their lives in Canada. Shlomo soon re-established himself as a master Hebrew instructor at Montreal’s Herzliya High School in addition to editing Hebrew textbooks. Chana became a respected private-duty nurse in her adopted city’s Jewish General Hospital. Chana and Shlomo have five grandchildren, one of which is named after his Uncle Ephraim.

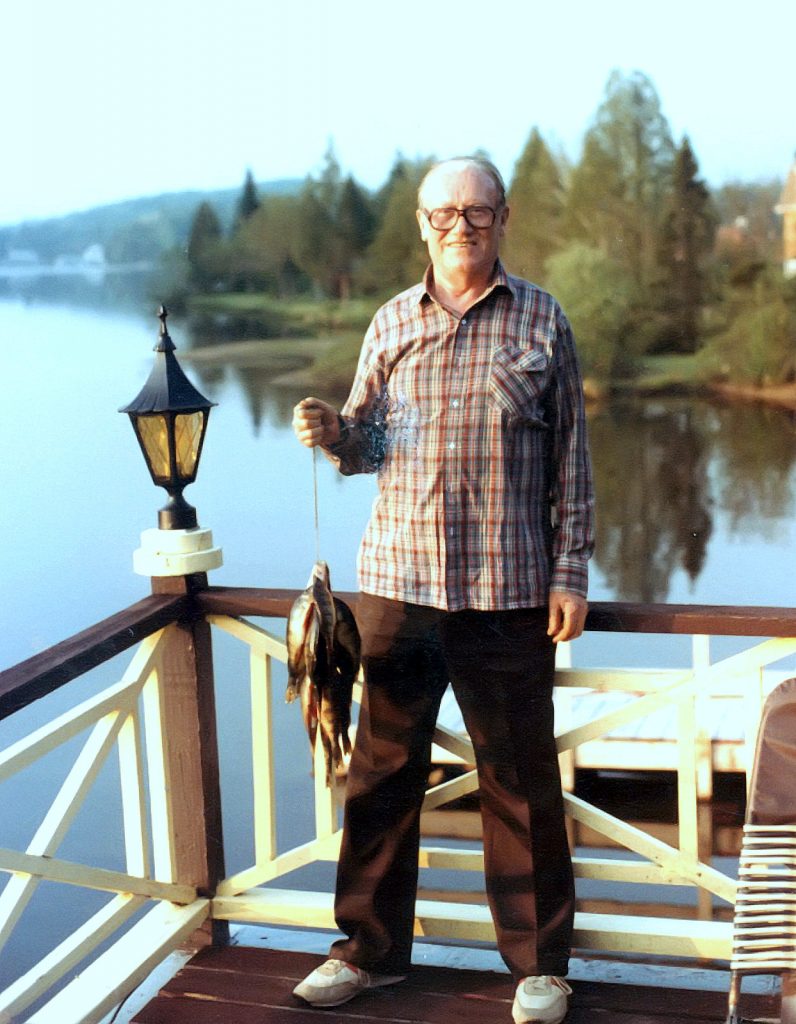

Shlomo often looked back upon their partisan days and reflected on how strong and proud they were to be in the forest, alive and free.

Shlomo passed away on December 14, 1997, at the age of 83.