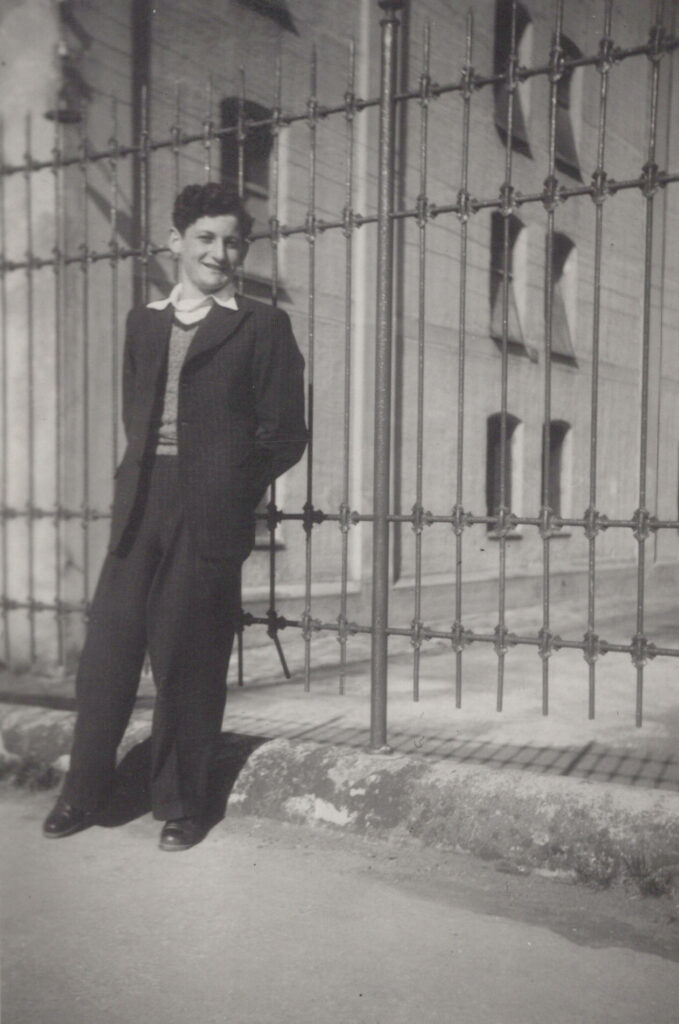

Jack (Idel) Kagan was born on April 7, 1929, in the town of Navahrodok, Poland (current day Novogrudok, Belarus). He lived in a large house with his parents, Yankel and Dvore, along with his sister Nechamah, his uncle Moshe, his aunt Shoshke (the two sisters, Dvore and Shoshke, had married two brothers), and his cousins Dov (Berl) and Leizer. Together, the two families ran a small production factory and a leather goods shop specializing in gloves, shoes, saddles, and boots. His aunt helped run the family store, while his mother ran the home. Jack always described his home and life in the shtetl as idyllic.

With great fondness, Jack recalled how one summer, when he was about ten years old, his father invited him to accompany him to the big city of Minsk for the summer fair, where the latest fashions would be on display. For a small child to venture so far from home was a big adventure. His father searched out the most stylish leather goods, purchased samples, and took them home, where Moshe would reverse engineer them. Within no time, the little Jewish shop in the town square was selling the latest fashions from the big city to the delight of the local citizenry.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed in August 1939 by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Poland was divided between the two powers. On September 17, the Soviets invaded Poland from the east. Novogrudok was under Soviet occupation until June 1941, when Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and invaded the Soviet Union.

Large sections of Novogrudok were destroyed during the German bombings. German forces occupied the town on July 4, 1941, and the persecution of the Jewish population was put into effect immediately. Jewish homes were plundered, and anti-Jewish laws were promulgated. The Jews of Novogrudok and its surroundings were systematically murdered in a number of mass killing operations from July 1941 to May 1943.

On December 6, 1941, the Jews of Novogrudok and the surrounding villages were forcibly taken out of town to the large courthouse. They were allowed to bring only what they could carry. Selections were made, and over 5,000 Jews were taken away to their deaths and buried in mass graves. Jack and his immediate family were among the remaining Jews taken back to town and confined in the Novogrudok Ghetto. Every day, twelve-year-old Jack and his father were marched down the hill back to the courthouse, which had been converted to workshops to make boots, gloves, and saddles for the German Army.

After another selection and mass murder, the ghetto was closed, and the remaining Jews were moved permanently to the work camp. In the harsh winter of 1942, Jack made his first attempt to escape to join the Bielski partisans, an all-Jewish partisan group that was operating in the forests. With a small group of fellow Jews, he slipped through the main gate and ran to the forests. While crossing a small frozen brook, the ice cracked and Jack fell in, soaking his wool-lined boots. Realizing that he would soon die of frostbite, Jack was forced to return to the camp on his hands and knees. Once inside the camp, a fellow prisoner, a dentist by profession, cut through the boots which were frozen to his feet and amputated Jack’s gangrenous toes, thus saving his life. No longer on the camp’s work register and unable to walk, Jack had to stay hidden–if he was discovered by the guards, he would have been killed immediately.

On May 7, 1943, the Nazis once again made a selection in the camp. This time, Jack’s mother, sister, aunt, and uncle, who were also workers in the camp, were tragically murdered. Shortly after the massacre, Jack’s father was transferred to another camp and was never seen again. Jack was left alone. He was unable to work and unable to earn his bread ration. His life was saved by the generosity of others.

After that massacre, the realization that no one would be left alive led to a decision by the remaining Jews in the ghetto to escape at whatever cost. After evaluating several options, they decided to dig a tunnel from below the last of the bunks and escape from the camp in a desperate attempt to join the Bielski partisans. They used bags sewn from blankets to carry dirt to the attic. When the attic was filled, double walls were constructed to conceal the earth. From his hiding place on a top bunk, Jack watched as the tunnel lengthened. The remaining 220 Jews in the camp decided that everyone would escape; no one would be left behind to face certain death at the hands of the Lithuanian and Ukrainian guards.

After many trials and tribulations, by September 1943, the 200-yard-long tunnel was complete, together with wooden supports, a sliding trolley, electric lighting, and a fresh air supply. The escape organizers were concerned that Jack’s wounds would prevent him from crawling all the way through the narrow tunnel and would endanger the entire operation. In the end, they agreed to let him go out last.

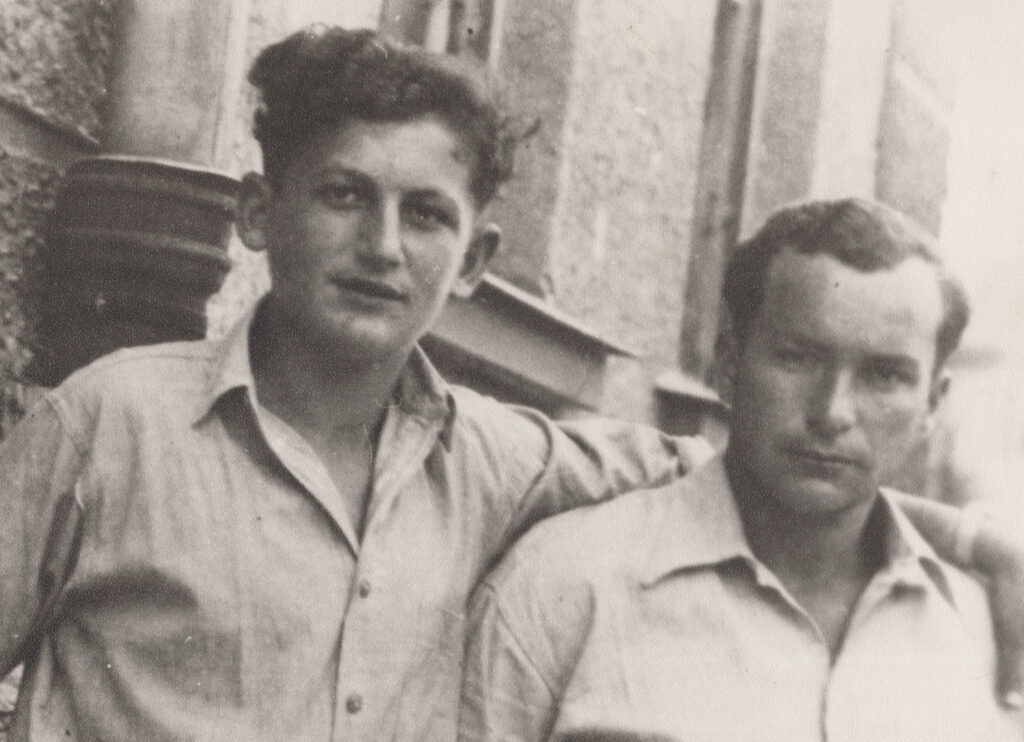

During the stormy night of September 26th, the entire camp of 220 Jews escaped. Unfortunately, as they exited, the guards saw moving shadows. Thinking they were under attack, they opened fire. 70 Jews were killed on the spot, or caught and killed before they managed to reach the forests. Jack, realizing that he would never make it before daybreak, decided to circle back around the town in the opposite direction. By doing so, he avoided the manhunt that followed and three days later made it safely to the forests and the Bielski partisans, where he reunited with his cousin Dov, who had escaped months earlier. Jack marched, as he said, not on his broken and bleeding feet, but on the strength of his spirit. A few people remained in the ghetto at the time of the initial escape, hidden in specially prepared places. They escaped three days later by simply walking out the deserted main gate.

After the Soviets liberated the area, Jack, Dov, and the other partisans—led by the great hero Tuvia Bielski and his brothers—marched back to Novogrudok, much to the consternation of many of the townsfolk who had already occupied the Jews’ houses. After a number of months, Jack, Dov, and the other survivors realized there was no future for Jews in such a large graveyard, and they made the decision to journey west.

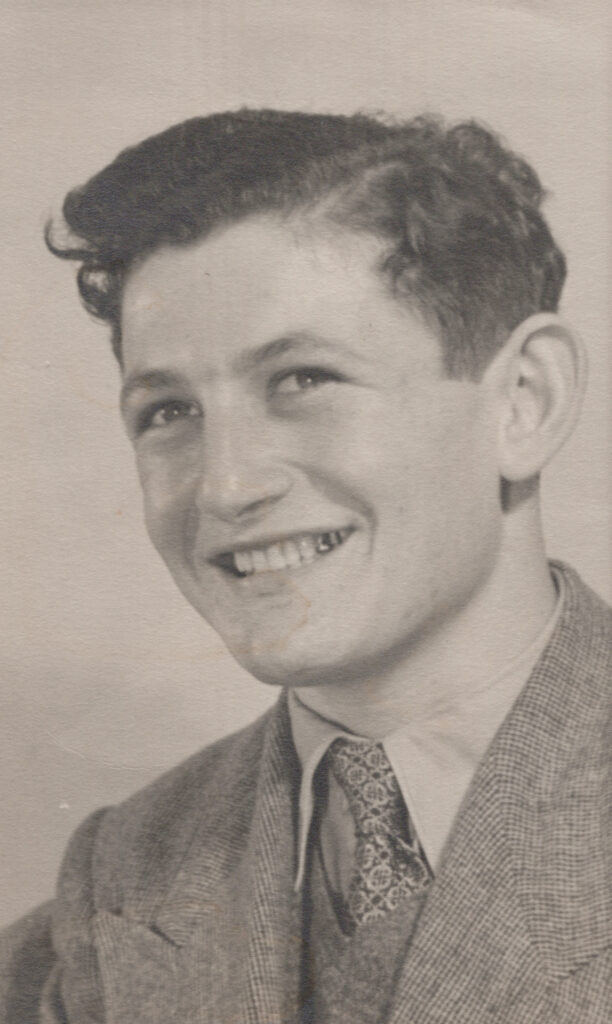

They stayed in a displaced persons camp in Germany, and in 1946, Jack managed to obtain a visa invitation from a distant cousin to enter England, while Dov attempted to reach Palestine on board the Exodus ship.

In London, without money, language, education, or connections, Jack worked hard at his family trade–leather cutting. He eventually switched materials from skins to plastic and opened his own factory following in the entrepreneurial spirit of his father and uncle. He quickly built a successful business. In 1955, he married Barbara Steinfeld, and together they built a Jewish home with their three children.

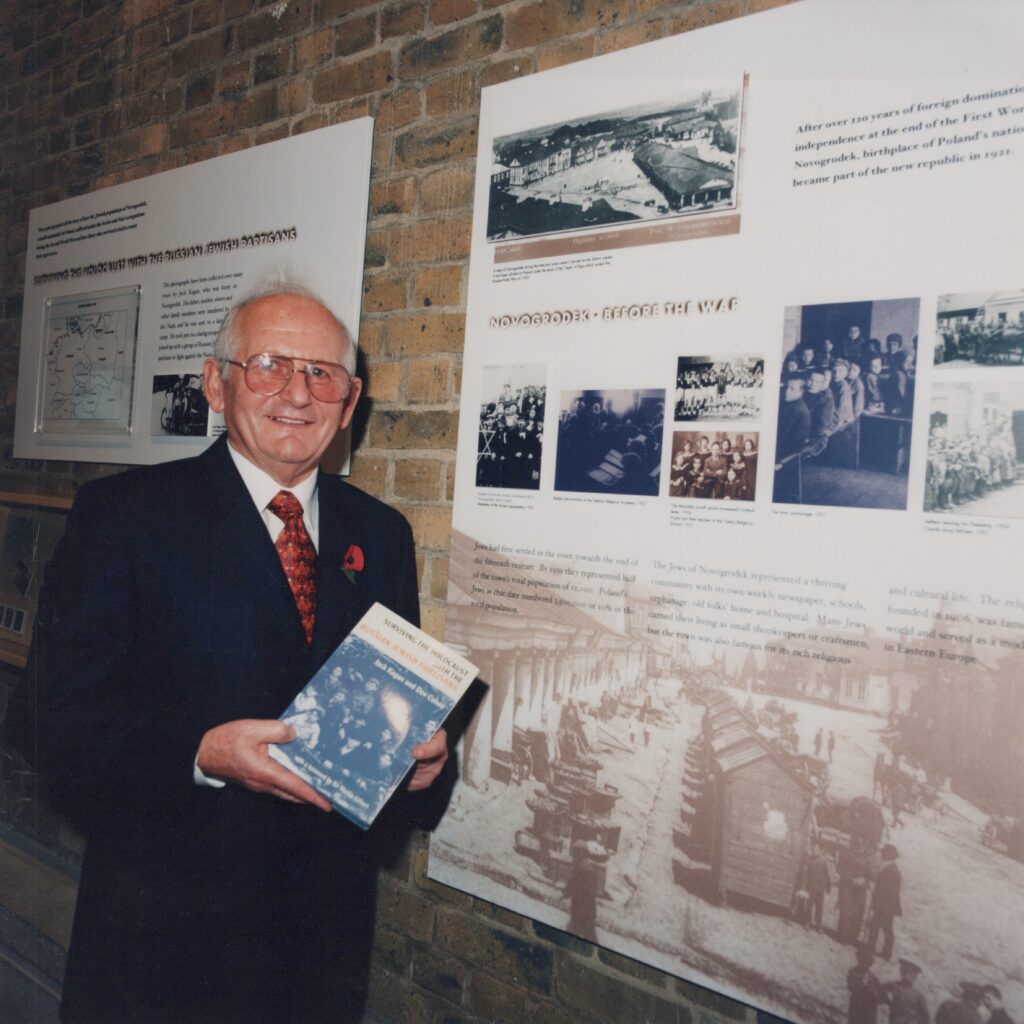

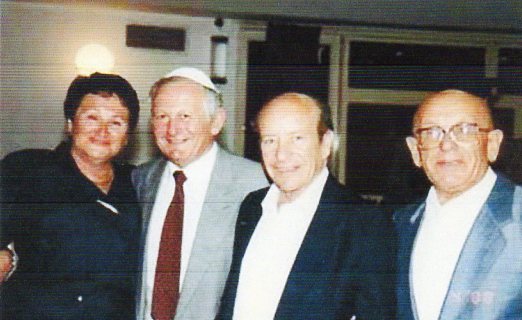

In the 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Jack returned to his hometown, Novogrudok. There, over the sites of the massacres, he established monuments to the Jews of the town. He also established a museum to commemorate the escape and the heroism of the Jewish partisans. He participated in a variety of educational programs and published three books about the escape, his beloved town, and the partisans. Recently a film was made called Tunnel of Hope about the greatest of escapes and the search for the remains of the tunnel by, amongst others, his children and grandchildren. (The film was co-produced by Michael Kagan, Jack’s son, and Tamara Vershitskaya the former director of the Partisan Museum in Novogrudok.) Jack is also prominently featured in JPEF’s film, A Partisan Returns.

In 2013, Jack was appointed by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to become a member of the Holocaust Commission, which would determine the future of Holocaust education in the UK. Jack was also awarded the Medal of Heroism by the Belarusian government and was honored by the Queen of England with the British Empire Medal (BEM). Jack passed away in 2016.