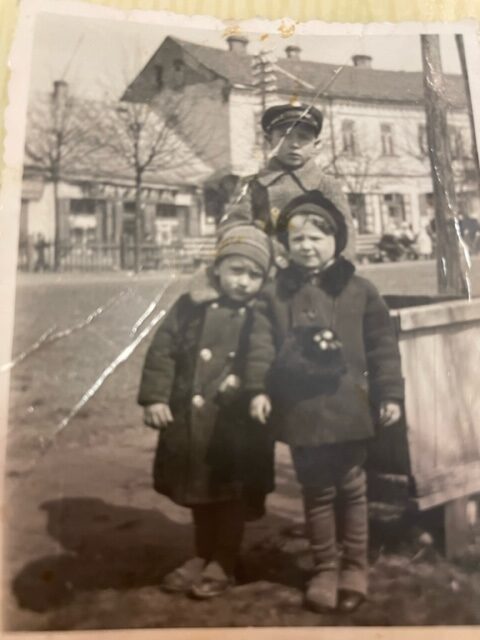

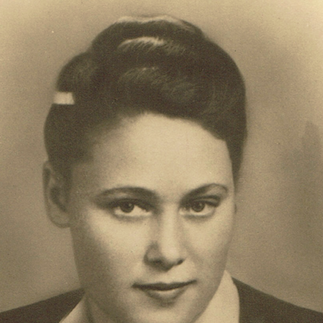

Helen Terris (née Elinka Cyderowicz) was born in Lida, Poland on September 8, 1935, the only child to mother Esther Thurston Cyderowicz (née Esia Thurston), a homemaker, and father Aaron Cyderowicz, a businessman. Before the war, Helen and her family lived a comfortable and privileged life. Her father went on frequent business trips and brought her home lavish gifts. She remembers on one business trip when she was three years old, he brought her home a fur coat.

Lida was a small town of roughly 60,000, of which 12,000 were Jews. Although there was an underlying antisemitism problem in Poland and incidents of antisemitism took place from time to time, the Jewish population lived rather peacefully among the general population of Lida. Lida had synagogues, a Hebrew day school, and an institution for higher learning. All of that came to an abrupt end in June of 1941 when the Germans invaded Lida and immediately enforced new rules. Jews were not allowed to walk on the sidewalks and not allowed to speak to non-Jews. Jewish men were prohibited from going to work, and children from going to school. All Jews were forced to wear a yellow Star of David patch. The Jews of Lida had been marked.

Helen and her family were forced to move out of their home and into the Lida ghetto. There was terrible overcrowding; disease and hunger spread throughout the ghetto. From time to time, the Germans performed roundups of the ghettos and people would hide wherever they could to evade the Nazis. On one of those roundups, Helen’s father, Aaron, was picked up. Helen and Esther never heard from him again. They lived in the ghetto until early May of 1942.

Rumors began to spread in the ghetto that mass graves were being dug on the outskirts of town. Helen could feel a terrible and impending doom spread throughout the group. On the evening of May 7th, 1942, the Nazis arrived in the ghetto and announced that at 8:00 the next morning, everybody was to vacate their homes. Anyone left behind would be shot.

On the morning of May 8th, 1942, Helen awoke to a gray and cloudy sky, as the rain lashed down outside. Some mothers tried to wrap their babies in blankets, hiding them under beds and closets before the Nazis came. There were some elderly people too sick to leave their beds. The Germans arrived to the ghetto and went from house to house, vacating each home. They found every baby, every elderly person, anyone trying to hide, and shot them dead. They did not rest until they were certain there were no people left alive in the homes of the Lida ghetto, as they had promised.

Those who had been rounded up were told to line up family by family in the city square. The Nazis set up a table in the front of the square and called each family to the table. If the family had a man who looked strong enough to work, that family was told to step to the left, which meant life. When Helen and her mother approached the table and the soldiers looked them over, all they saw was a woman and a scrawny girl. They sent them to the right, which meant death.

As Helen and her mother, Esther, were being marched towards the woods, they could hear the gunshots ringing out and people screaming. Esther looked at Helen and said to her “You know we’re going to die anyway? We have nothing to lose.” When one of the Nazis guarding their group turned his head for a moment, Helen and Esther ran into the vestibule of a nearby house. Three dead men were lying on the floor in a large pool of blood, their bodies still warm. Helen’s mother scooped up the blood in her hands and covered Helen from head to toe in their blood. She then did the same to herself. They laid on top of the dead men and Esther said that if Germans came in, to not breathe and pretend to be dead. Towards dusk, two Germans came into the vestibule, lit their cigarettes, and started a conversation. Helen thought to herself, “How long could I possibly hold my breath?” She was only six years old. One of the soldiers picked Helen up by the back of her neck, held her at arm’s length from him, and pulled out his revolver. He put the revolver next to her head and Helen remembers hearing the sound of him cocking the pistol. The other Nazi said something to the soldier holding Helen, distracting him, and causing him to throw her back onto the pile of dead people. The other soldier walked over to Helen’s mother and touched her shoulder. “The big one is dead,” he remarked. Esther’s will to live was so strong that she managed to hold her breath the entire time. They finished their cigarettes and left.

Helen, her mother, and the 3,000 others who had survived, returned to the ghetto, feeling dejected and morose. They had seen up-close what the Nazis were capable of doing. However, they still held on to a splinter of hope amongst the slaughter and tragedy. Helen recalls in her testimony: “The only thing that kept us going, the only thing that gave us a glimmer of hope was the knowledge that no war lasts forever. Sooner or later all wars do end. And if we could only hold out one more week, one more day, one more hour, maybe, just maybe, this madness would end and we would live.”

They lived with that glimmer of hope in the Lida ghetto until September of 1943. The Germans announced that the Lida ghetto was being liquidated. Everybody was to pack a small suitcase and be in the city square by 8:00 the next morning, September 17th.

By then, some rumors had reached the ghetto of what was taking place in the concentration camps, but nobody believed them. People questioned how human beings could put other human beings into ovens.

But Helen’s mother believed it. Once again, the Jews of the Lida ghetto were being marched towards their death, this time towards the train station. As they were being led to the train station, Esther pushed Helen out of the group they were marching in and told Helen to go to the Kriegers, a gentile family with whom they were good family friends.

The Kriegers were childless. Helen was fair-skinned and spoke Polish like a native, so she might pass as their child. The Kriegers always told Helen’s parents that if anything happened to them, Helen could live with them and they would treat her as if she was their own.

When Helen arrived at the Krieger’s home and asked Mrs. Krieger if she could stay, she told Helen that they could not keep her. They were afraid. Helen begged and pleaded with her. She said she would stay in the attic, or the basement, or anywhere, and she would be so quiet that nobody would know that she was there. But they would not take her, so she had no choice but to return to the train station.

When she arrived at the station, it was a scene of chaos. There were 3,000 people and their suitcases and a group of Nazis guarding them with their rifles. The train was bound for the Majdanek death camp.

Helen looked everywhere but could not find her mother. She did however find one of her cousins, Matle, who was about 20 years old at the time. Matle told her to not worry about finding her mother and to wait until they got to their new destination to find her.

Helen waited in the group of others, until a man, whom she did not know who he was, but who appeared to have known her, told Helen that her mother had run away. At this moment, she knew she had to get away from the station. She told her cousin she must leave and find her mother, but Matle gripped her hand and wouldn’t let Helen go, out of fear that she would be shot if she tried to run.

As they began to board the train, Helen escaped her cousin’s tight grip, yanked her hand away, and ran around the side of the train, escaping onto the other side.

She started running, with no idea of where she was going. All she knew was that she couldn’t get on that train if her mother wasn’t on it. She ran and ran until there was nothing but farmland in front of her. She then remembered that one of the farms belonged to a family named Leschinsky, whom her family had known. When she arrived, the Leschinskys hid her in the barn with the animals. Helen was terrified. Every time she heard people coming towards the barn, she didn’t know if it was Mrs. Leschinsky coming to bring her food, or if it was a German who had found out she was hiding with the family. After a few days of hiding there, Helen’s mother walked into the barn. Helen explained to her what had happened at the Kriegers and the train station and her mother declared it a miracle. “It was one of many miracles to come,” Helen recalls.

They couldn’t stay long because they knew they were in danger and that they were putting the Leschinskys in danger. The only place left to go was to the woods on the outskirts of town, to join the Bielski partisans. Helen and Esther dressed in peasant clothes given to them by the Leschinskys. They made their way towards the woods, walking mostly at night to avoid being caught. They walked through burned-out and bombed-out villages, where they foraged for any food that they could find. After a week of trekking, they made contact with the Bielski partisans.

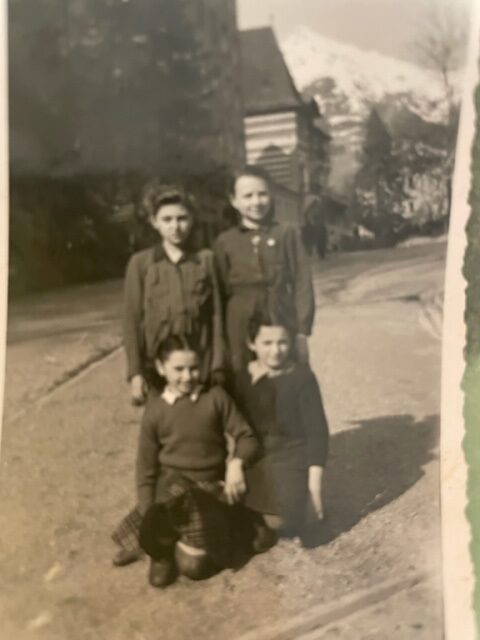

Although grateful to have finally reached the partisans, life with the Bielskis was very hard. The Bielski partisans were constantly bombed by the Germans, who knew that there were people in the woods. Russian winters are notorious for their harshness and sub-zero temperatures and food was very scarce amongst the group.

Helen, still a child, attended the school the partisans had formed and, like the other partisans, found ways to earn her keep. Helen and the estimated other 60 children of the camp had no books, pencils, or papers, but they had a school where they learned everything by rote. And they followed the rules of the Bielski partisans, including the rule that, if you didn’t work, you didn’t eat. Partisans either had to go on sabotage missions, procure food, or fulfill other important tasks. For example, Esther’s duties in the camp were maintaining and working in the bathhouse. As children, their job was to entertain. Every night, Helen and the other children put on a show. They cleared an area for a small stage, and they would sing, recite poetry, and dance. It gave the others a feeling of hope to see them performing.

Now, the war was almost over. The German forces were spread so thin that they had bigger issues to deal with than the partisans in the woods. Whatever acts of sabotage the Bielskis succeeded with, the Germans could fix a few days later. However, these acts of sabotage thwarted the German war effort and caused a nuisance for them. This was one of the great feats of the Bielski partisans: to impede, if just for a moment or a day, the German war machine.

By July of 1944, it became very clear that the war was not going well for the German Army. Many German soldiers came through the woods, retreating. The Russian army was advancing and the Bielski camp was caught in the middle. There were skirmishes and battles in the woods, but this time, it was the German Army that was on the losing end. In July of 1944, Helen and the rest of the Bielski partisans were liberated by the Russian Army.

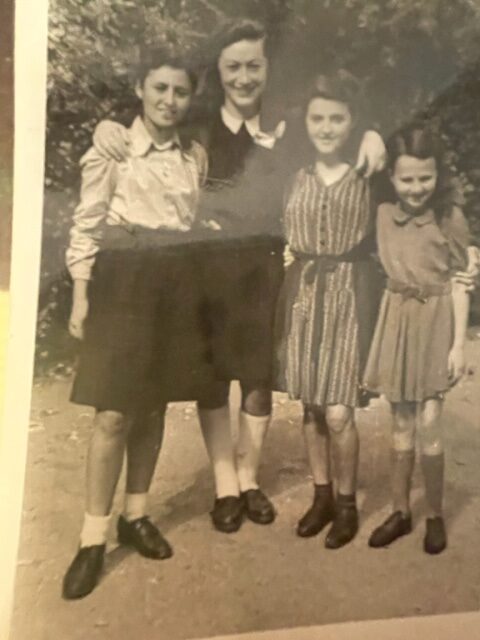

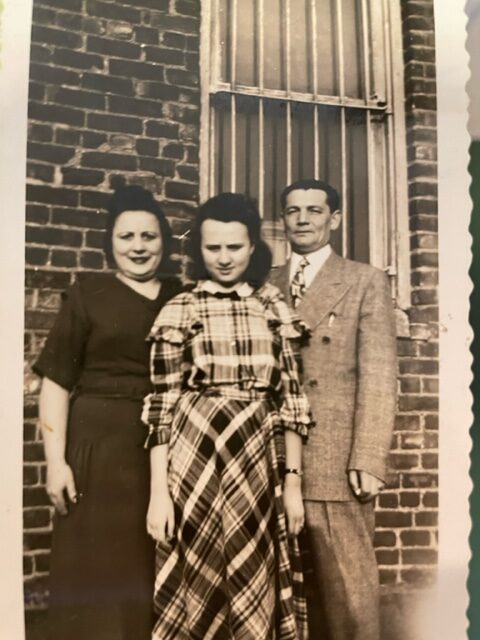

Following the war, Helen and her mother stayed at various Displaced Persons (DP) camps, first at the Bad-Gastein DP camp in Austria and later at Ebelsberg, just outside of Linz. In one of these DP camps, Esther met survivor Joseph Rosenbaum, who had lost his family. They were married there. Helen, her mother, and her stepfather immigrated to the United States via the SS Marine Flasher, which docked in Boston Harbor in January 1949. The family settled in Passaic, New Jersey. In 1949, at the age of 14, Helen entered the 6th grade with a teacher who also spoke Polish. This was her first year of formal education.

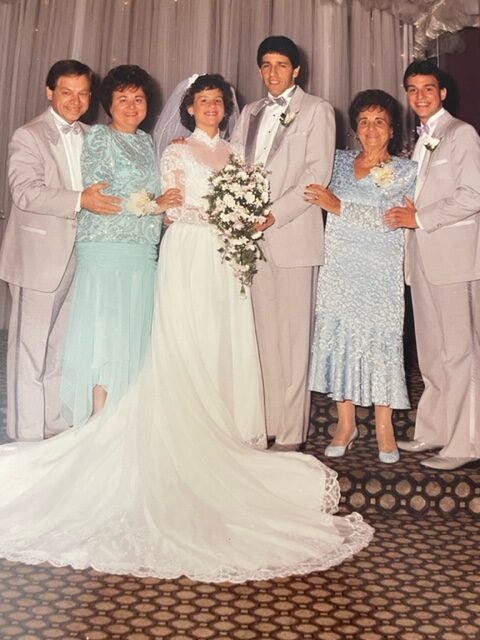

Helen later met her husband, Harry Terris, at a dance at the Armory in Newark, New Jersey. They were married on November 27, 1955, and resided in Passaic, New Jersey, where Harry worked as a pharmacist.

Helen has two children, Rita and Mark, two grandchildren, Jacqueline and David, and one great-grandchild, Michelle. Helen hopes to share her legacy with her children, grandchildren, great-grandchild, and the world, to remind everyone that “The human spirit can overcome many cruelties and many adversities that life puts in your path. The human spirit can survive and persevere.”

Helen belonged to the Holocaust Center at Brookdale Community Center in Lincroft, NJ, for many years where she participated in several Holocaust programs throughout New Jersey, including speaking with soldiers and employees at Fort Monmouth, and speaking with students at local schools, including her grandchildren’s.

Helen emphasizes the importance of children Holocaust survivors sharing their stories: “For many, many years, I could not speak about my past. It was just too painful for me. But now I don’t have a choice…A great many of the survivors have passed on and many others’ memories are no longer viable. It is now up to us, the children survivors, to keep their stories alive. So it’s never repeated, and it’s never forgotten.”