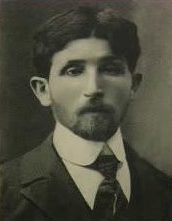

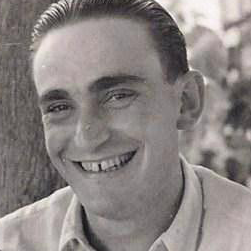

Chaim Wolfe (Schmuel Chaim Wolfowicz) was born on January 12, 1914 in the village of Ravniki near Novogrudok, Poland. He lived with his parents, Eliezer Nachum and Merka, and his five siblings: David, Sarah Esther, Chaya Simcha, Mayer, and Rivka. Jews had always lived in harmony with their Christian neighbors in Ravniki. The relationship between Jews and non-Jews deteriorated as interwar economic depression resulted in ethnic tensions and increasing antisemitic government regulations.

Chaim was drafted into the Polish Army in 1937 when he was twenty-three. During his eighteen months as a soldier, he endured many antisemitic experiences. Upon his return home, he worked for a short time as a painter. He was mobilized when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. Chaim’s unit was soon captured and interned in Stalag IA, a POW camp in the German District of Stablack. Initially, all the Polish prisoners were left to sleep outside in the mud and were eventually provided with tents, each holding one hundred men. As the first prisoners, they were forced to build the camp structures. Eventually, the Jewish and Christian Polish soldiers were separated into different barracks. The Jewish prisoners were singled out for particularly brutal treatment by the Germans and by the non-Jewish Polish POWs. For the next year, Chaim was assigned to work in a German plywood factory. He found sustenance in frozen potatoes dug from nearby fields, and scraps of food scavenged from his captors’ garbage.

In late 1940, Chaim and his fellow Jewish POWs were transferred to the transit camp Stalag II-B in Hammerstein, Germany, then put on trains headed for Biała Podlaska near Lublin. Biała Podlaska was overcrowded and under the German Army’s control. The Jewish inhabitants were registered and required to perform forced labor; however, a formal ghetto had not yet been created. Chaim was sent to a forced labor camp in Lublin, where he endured beatings and unbearable hunger. In the spring of 1941, Chaim attempted to escape but was caught by the Gestapo and taken to the Judenrat’s employment office in Biała Podlaska. He was assigned heavy labor, unloading telephone poles from German trains, loading and unloading grain, and painting houses for German officers.

A Jewish family in Biała Podlaska, the Poncheks, took Chaim in while he was plotting his next move. Since he was alone and unaware of his family’s fate, Chaim was able to make independent decisions. One night, under cover of darkness, Chaim found his way to a farm where he found employment using a false Polish name. While he worked in the fields for the Staniszewski family, Chaim made contact with Soviet POWs who were incarcerated in a nearby camp. He used his new freedom to report German military locations to the prisoners until one night he was alarmed to hear shooting in the fields. In the morning he encountered a German soldier standing guard and he asked what had happened. The German told him they were looking for a Jew who was relaying military information to the POWs. Chaim quickly found a hiding place among the haystacks and, at nightfall, returned to the Ponchak home in Biała Podlaska.

A ghetto was formed in Biała Podlaska in the summer of 1941. During the spring and summer of 1942 mass shootings of local Jews were perpetrated in the nearby forests. Another 3,000 were deported to their deaths in Sobibor. In September, when the Germans began to liquidate the ghetto, Chaim went into hiding with the Poncheks in their attic. After three days they left their hiding place, and Chaim returned to work where he was arrested by the Gestapo. He was forced to dig graves, clean outhouses, and put Jewish household items on trains bound for Germany.

Chaim managed to survive brutal forced labor in various camps until the spring of 1944 when he was sent to Majdanek, a concentration and extermination camp. There he witnessed the existence of gas chambers for the first time. Chaim worked in the munitions factory. As Soviet forces advanced, he was crammed onto a train headed towards Auschwitz. Chaim noticed a small window in the hot cattle car and had an idea. As darkness fell, some of the other Jews in the compartment helped heave Chaim through the window. Once again he managed to escape, jumping into a pit on the side of the train tracks.

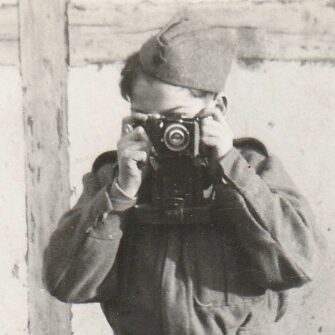

Chaim waited until the train was out of sight before running into the woods, where he wandered for days on end. He was hungry and wounded, and resorted to using his urine to clean his wounds. He obtained food by scavenging barns and begging from farmers. He survived this way for two months until he came across a group of Soviet partisans. At first, the Soviets suspected he was a spy and would not accept him into their ranks. He managed to convince them he was Jewish and a former Polish soldier. Chaim became a partisan.

One rainy night, Chaim’s group was surprised by a German military unit. During the shootout, Chaim managed to kill a high-ranking officer, earning a promotion to group leader. He continued to lead his partisan unit for the next two months in raids demolishing German trains and communication posts. By the end of 1944, the Soviets had liberated eastern Poland and Chaim found his way back to Lublin, where he once again joined the Polish Army. Only then did Chaim learn the fate of his family. They had been lined up and shot – buried in an anonymous mass grave.

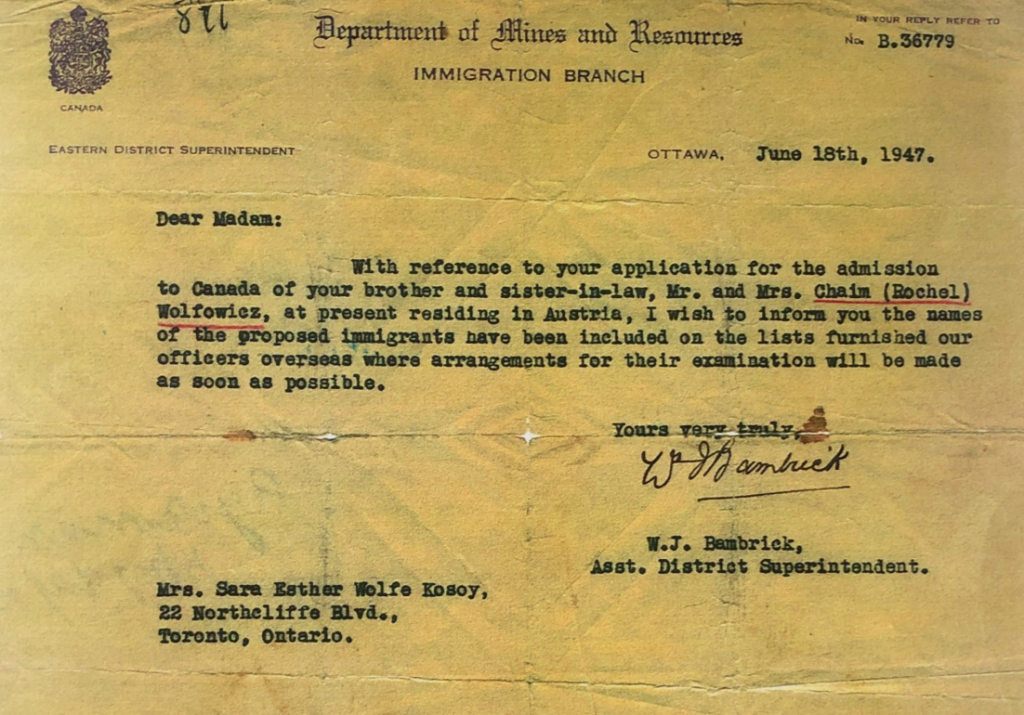

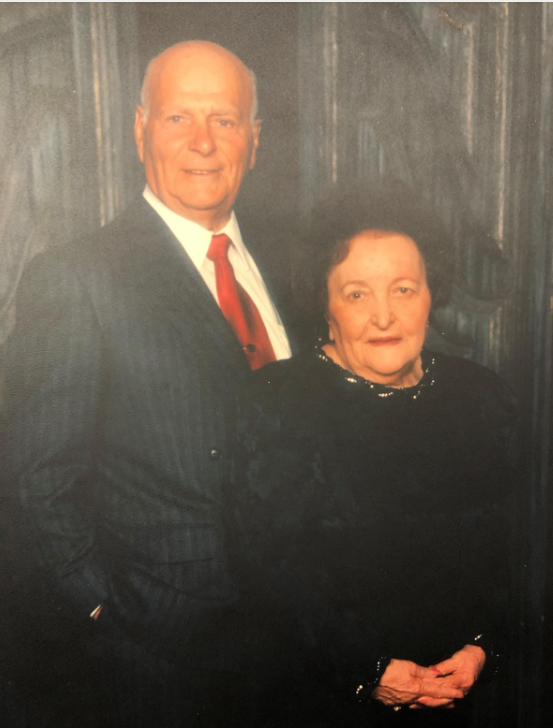

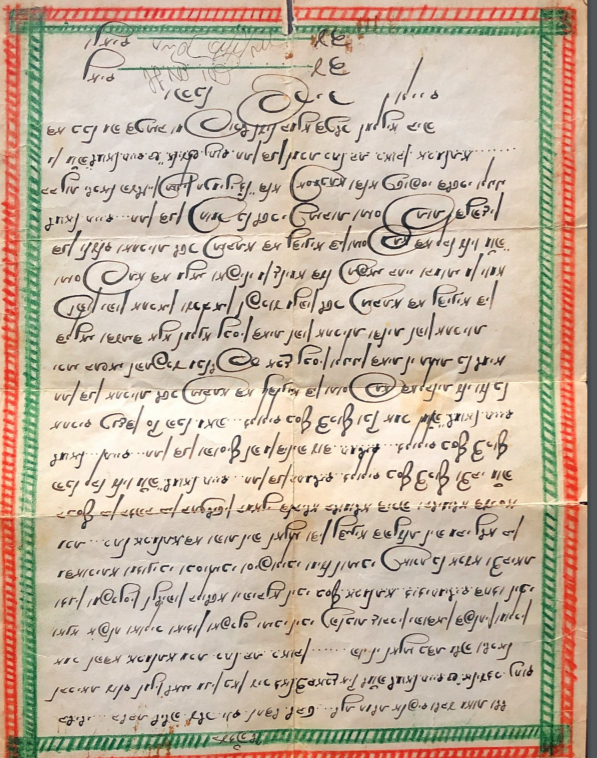

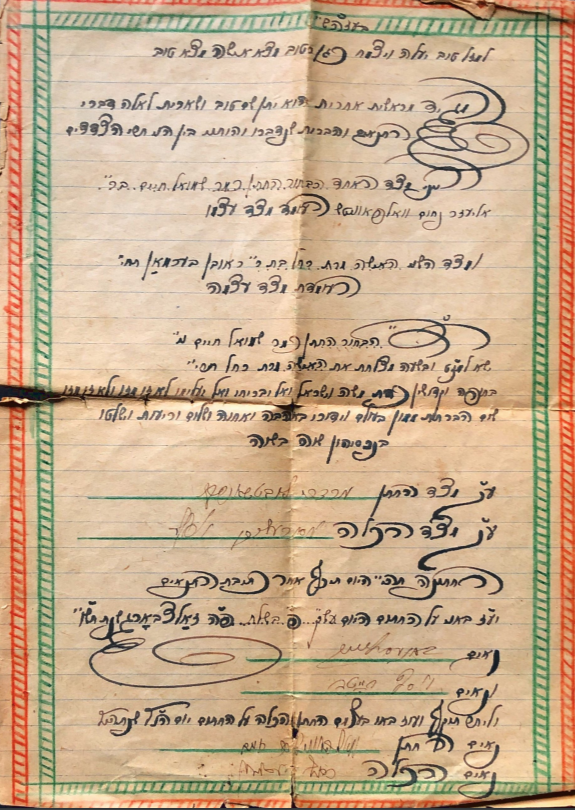

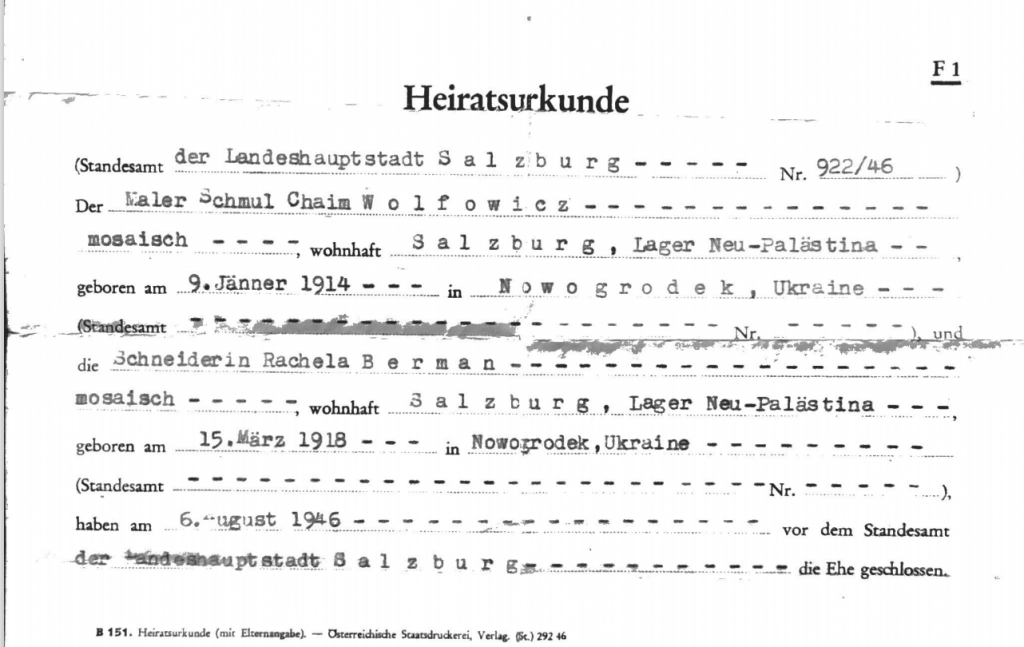

While he was serving the last months of the war in the Polish Army, Chaim met Rochel (Rose) Berman Ostashinski in Lodz. Rochel and Chaim had known each other in Novogrudok before the war. Rochel and her first husband, Eliahu Ostashinski, had been partisans with the Bielski Brigade. Eliahu was killed in battle on the very day they were liberated by the Soviets in July 1944. Chaim and Rochel were married on January 17, 1946, in the Salzburg DP camp of Parsch. Two of Chaim’s siblings had immigrated to Canada before the war, along with an aunt and uncle. Chaim and Rochel decided to join them and arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on February 13, 1948.

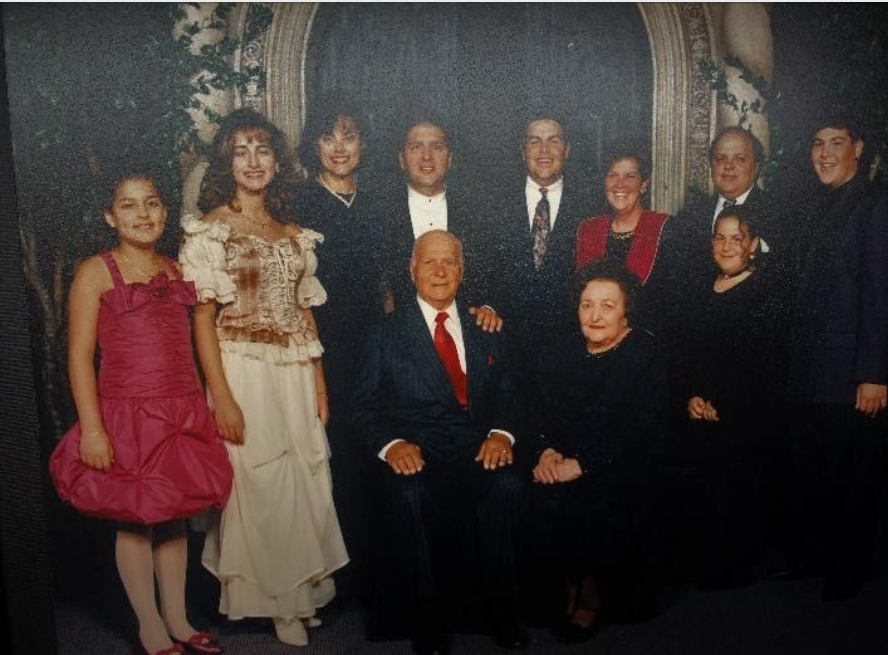

Chaim and Rochel moved to Toronto, where they worked hard to rebuild their lives and start a

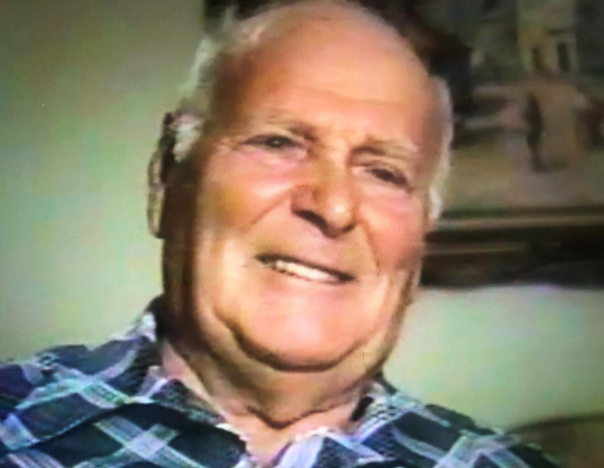

family of their own. Chaim adopted the English name Harry Wolfe, which he used when doing business. Chaim held various jobs and owned several businesses to support his family, first working as a painter as he had in Poland. With hard work, long hours, and the support of his wife, he managed a men’s clothing store. Later, Chaim owned and operated various hotel bars in Ontario.

Later in his life, Chaim began to share his wartime experiences because he wanted to educate the next generation on the lessons of the Holocaust. He was a proud war veteran and participated in memorial activities. Chaim always kept his strong religious faith.

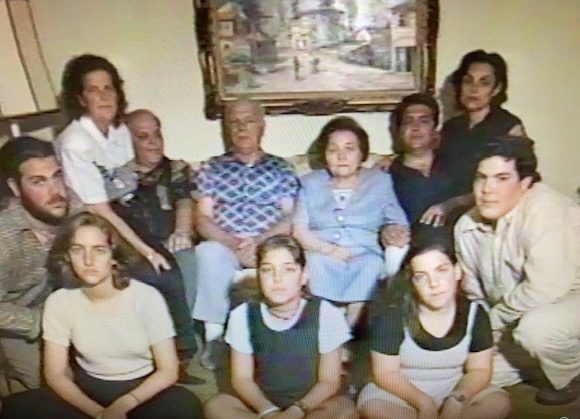

In June 1994, Chaim returned to Belarus with his two sons. They joined a large international group commemorating the unveiling of a memorial to the 5,100 murdered men, women, and children including his parents, sisters, and other relatives of his and his wife’s, Rochel.

Chaim sought reminders of his youth while walking through the streets of Novogrudok – bravely and defiantly declaring in Yiddish “I am a Jew, and I am back, I am with my sons and Hitler did not defeat us.”

Chaim passed away on September 28, 2005 at the age of ninety-one. He is survived by two sons, Martin and Ralph, five grandchildren, and ten great-grandchildren.