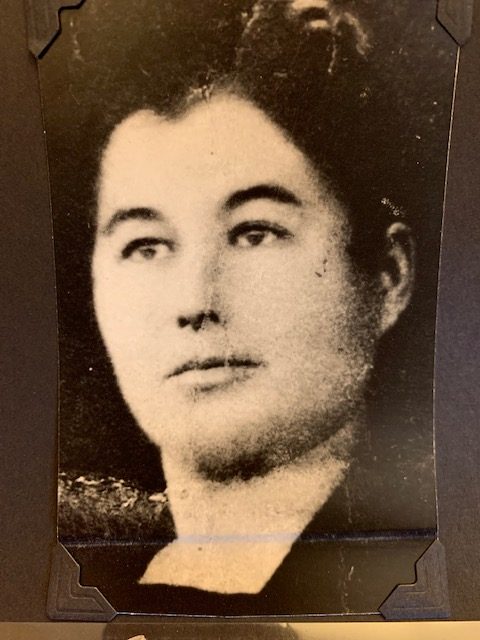

Freida Szewryn Rubinoff was born on December 12, 1927, in the small town of Lenin, Poland to Chaim and Elka Ziklig Szewryn. She grew up in a religious home and had a happy childhood with her four sisters Faiga, Hannah (Henya), Rochel, and Sara. As a child, she enjoyed swimming, exploring nature, and picking fruit from the many orchards in her town. However, from a young age, Freida witnessed acts of antisemitism that escalated when WWII began.

In September 1939, Poland was divided between Germany and Russia under the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact. In the summer of 1941, Germany broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The Nazis occupied Lenin and worked collaboratively with Polish Police to enact anti-Jewish laws. Because Freida’s father was a shoemaker, he was sent to the Hancewicze (District of Luniniec) labor camp. There, he sabotaged the German war effort by not completely hammering the nails into the heels of boots, causing them to pierce through the leather and irritate soldiers’ feet.

The Jews of Lenin were soon crowded into a ghetto, where hunger was a constant battle. One day, Freida was digging for potato peels in an alley when she was caught by the Nazis and thrown into prison. When her older sister Faiga (who did errands for the Polish Police) found out, she pleaded with the Polish Police to release Freida, and they finally complied. Around this time, massacres soon began in Lenin. Freida saw her neighbors being taken away and locked into a synagogue that was set on fire. She never forgot the harrowing sound of their screams.

On August 14, 1942, the Nazis carried out a mass killing in Lenin. Twelve-year-old Freida, her mother, and sisters, as well as the remaining townspeople, were led out of town to a large pit, where they were forced to undress. Freida’s sisters were immediately killed, falling into the pit as they were shot. Freida was not injured. As her mother lay bleeding and dying, she told Freida to cover herself with her blood so the Nazis would think she was dead too. This saved Freida’s life. Once the Nazis left, she escaped from the pit and fled into the nearby forest.

Freida stayed with different farmers in the area, sleeping in root cellars and working for them as slave labor. Afraid of being discovered by the Nazis, one farmer eventually told Freida that she must leave. He informed her that her cousins were in the woods and were searching for her. He took her, hidden in his wagon, into the woods to meet them. Freida was soon reunited with her extended family in the forest and lived with them that frigid winter, often hiding and sheltering under the snow. One day, they heard the Nazis approaching and her baby cousin began crying. Her aunt, uncle, and baby cousin were instantly shot. When everything was quiet, Freida managed to flee from her hiding place.

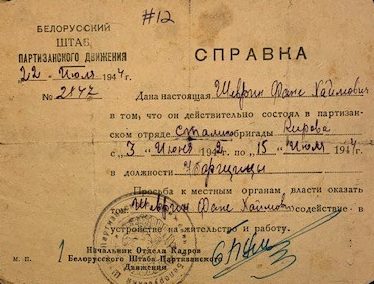

She soon came across a Russian partisan group, the Stalin Detachment of the Kirov Brigade. There, she was miraculously reunited with her father who she thought was dead. He had fled the labor camp and returned to Lenin when he heard of the mass killings, only to discover that his family had been murdered. He had joined the partisans as a shoemaker. Life in the partisans was difficult, and the winters were bitterly cold. Freida cooked, cleaned, boiled clothes to kill lice, gathered food, and laid bombs underneath train tracks to sabotage German transportation.

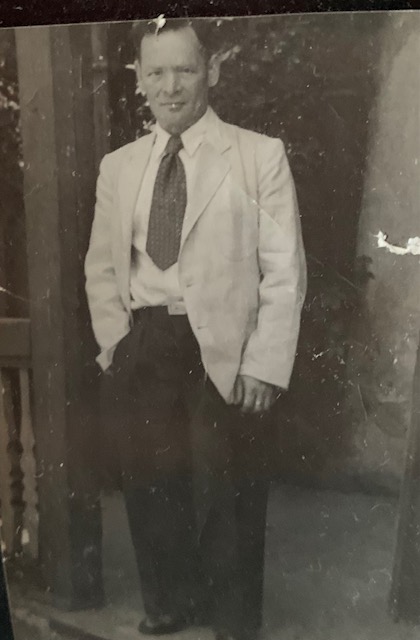

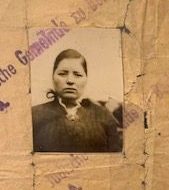

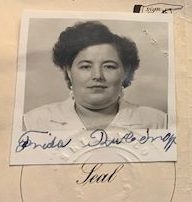

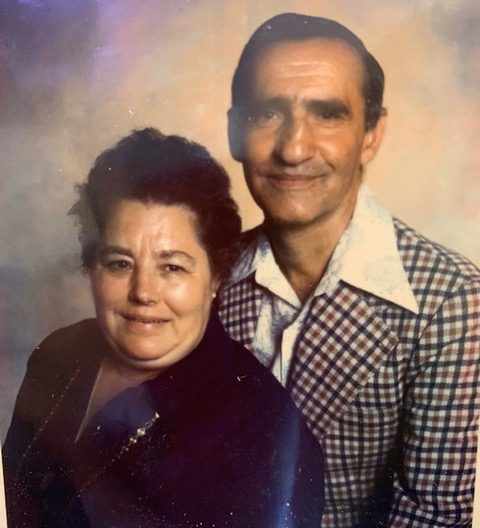

When the war ended, Freida was told that if she went to Berlin she could receive a medal for her work in the partisans. However, fearing that it was a ruse, she never went. Instead, she traveled with her father to a Displaced Persons camp in Lampertheim, Germany. Her father remarried and her abusive stepmother demanded that sixteen-year-old Freida leave their home and get married. Freida’s father arranged a marriage for her, choosing another Holocaust survivor, Irving Rubinoff. Irving was a young man born in Pińsk, Poland in 1924, who had escaped Nazi massacres in his ghetto and served as a Senior Sergeant in the Russian Army. In the Lampertheim DP camp, Irving worked as a certified machinist and taught locksmithing. Freida and Irving were married on May 22, 1945. In 1946, their oldest daughter, Elke (Ella, named after Freida’s beloved mother) was born in the camp.

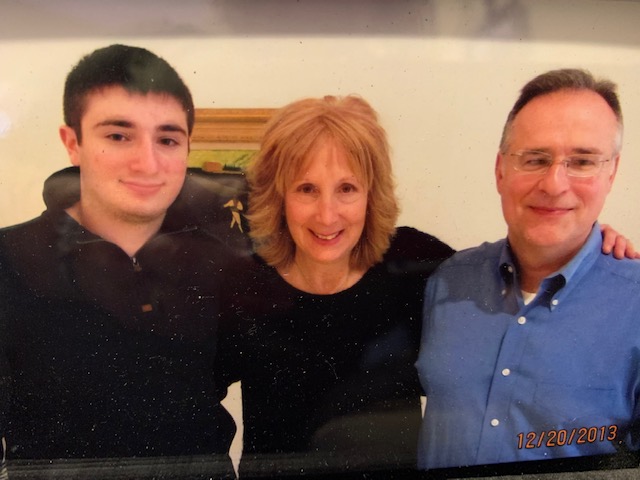

In August 1949, Freida, Irving, and their three-year-old daughter immigrated to Troy, NY on the SS General Howze. They both held a variety of jobs in the United States. Freida worked in a shirt factory and as a caretaker for the elderly, while Irving worked for Mohawk Mills, in a missile factory, and eventually owned a secondhand shop. They had two more children and eventually moved to Brooklyn, NY. Freida and Irving have four grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Freida openly shared her Holocaust experiences, giving her testimony to Yad Vashem and speaking to local schools and organizations. She often talked with other Holocaust survivors, and they shared their experiences with each other. The trauma Freida lived through greatly affected her, and she frequently had disturbing flashbacks, depression, and nightmares. Despite these challenges, Freida was strong, resilient, and fun. She deeply loved her family and was an excellent cook, a legacy she has passed on to her descendants. Her story of bravery and survival has been an inspiration to her family and to the students and groups she spoke to over the years.