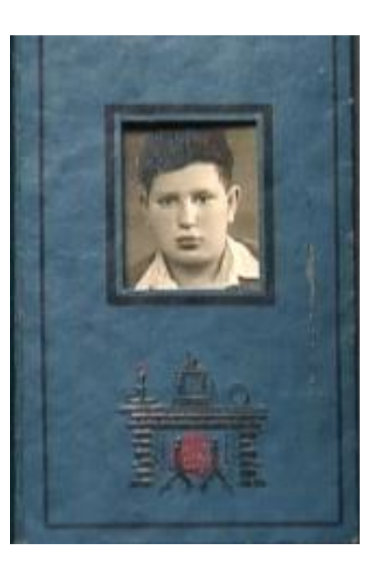

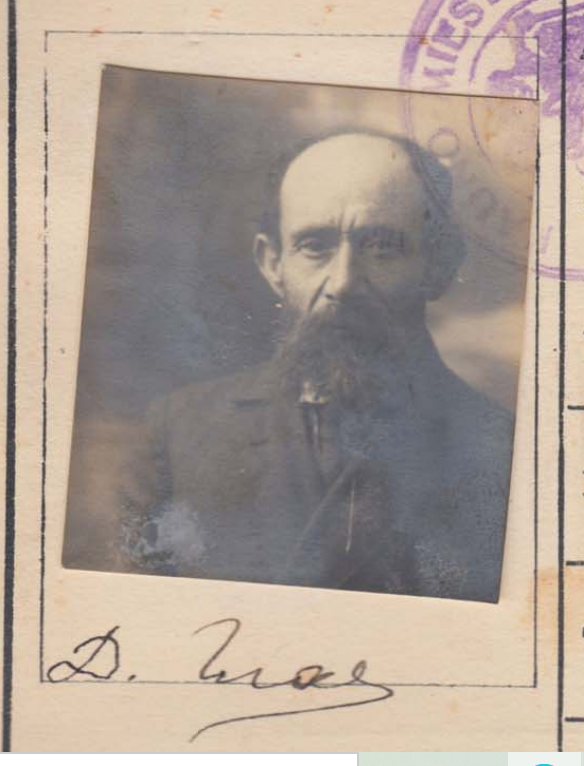

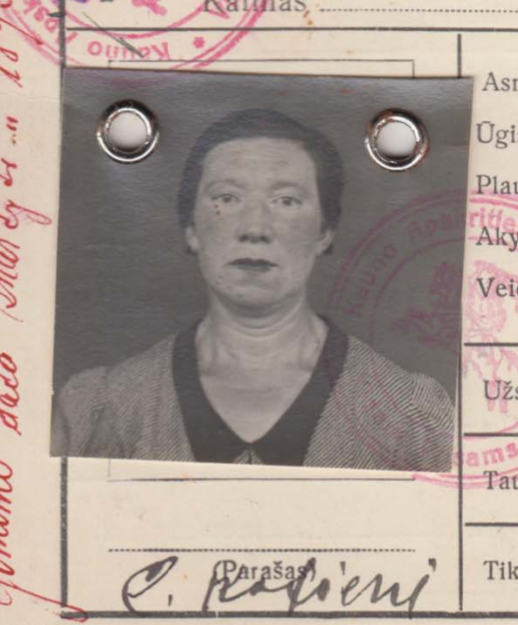

Boris Kot was born on May 8, 1925, in Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania. He lived with his parents Solomon Isaac Kotas (Mr. Kot) and Celia Kotiene (Mrs. Kot) (nee Glassiene), and his younger sister Basya who died in 1936. Boris helped in his family’s bakery, where they sold baked goods to both Jewish and Gentile customers and stores. Jewish life was vibrant in the center of Kovno until the Soviet occupation in 1940, which resulted in closed businesses, schools, and synagogues.

In June 1941, life drastically changed for sixteen-year-old Boris. The Germans launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union, which since June 1940 included Lithuania and the Baltic states, breaking the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact. A few days after the war began, the Germans occupied Lithuania. Many Lithuanians began killing the Jewish population and stealing their possessions before the Nazis took control. Boris’ grandfather and uncle were two of their victims. In July of that year, anti-Jewish laws were enacted, and a ghetto was formed. Jews had no rights and no citizenship.

On August 2nd, 1941, Boris was forced to help construct a fence around the ghetto. Shortly after, the Germans took Boris and other workers to the Fourth Fort and ordered them to dig a ditch. They were then ordered to stand aside. The sound of bullets filled the air, mingled with the cries of over fifty Jews who had been rounded up while looking for food. Boris’ knees went weak as he saw a young man in a brown suit fleeing the massacre. The young man was shot two yards in front of Boris. Boris and his fellow laborers were told to cover the grave with patches of grass to conceal the murder. He looked into the cloudless sky and thought: “Why doesn’t it rain? Why doesn’t it grieve?”

The Kovno Ghetto was divided into two parts: a small and large ghetto. On October 4, 1941, the Germans destroyed the small ghetto and killed many of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Boris and his parents were thrown out of the small ghetto and moved into the large ghetto, where they lived with extended family. Being under 18 years of age, Boris was not required to work; however, to obtain more food for the family, he worked hard to support his parents, volunteering to work in the city with a labor battalion where he could exchange items for food.

On October 28, 1941, the “Grosse Aktion” (The Great Action) began under the guise of a census. The Jews in the ghetto were forced to assemble, and a selection took place. German soldiers directed the Jews either to the left or right, to death or life. Boris stood with his parents behind his aunt, uncle, and cousins. Suddenly, Boris was in the line destined for life. The rest of his family were sent to the small ghetto and murdered the following day at the Ninth Fort. Alone and in shock, Boris returned to the ghetto and lived with his aunts and uncles, who had survived the selection. Suddenly, the cramped rooms were spacious, a harrowing reminder that thousands of Jews had been taken to their deaths.

Boris worked for a blacksmith in the ghetto in the spring and summer of 1942 until the Jewish Police rounded him up. They came in the dead of night, banging on his door and demanding to see his work permit. Boris had worked in a factory, the Kovno airport, and with the blacksmith, which was all documented on his permit. Despite this fact, they declared it was “no good.” They took Boris to a synagogue that had been turned into a jail, then put him on a truck bound for the Palemaonas work camp. Boris worked in a locomotive factory and constructed a channel to the river. The conditions were unbearable, and he nearly gave up. However, he was saved by a woman who obtained a job for him in the camp kitchen. There, he cleaned pots and pans and had enough food to gather his strength.

Boris and a fellow worker woke at 4 am each morning to deliver milk cans filled with coffee to Polish workers. At first, they were accompanied by German guards. However, after a while, they were permitted to walk by themselves. One morning in early 1943, Boris and his friend saw a train going in the direction of Kovno and jumped aboard under cover of darkness. Once they arrived in Kovno, they mingled with a Jewish group working a night shift and entered the ghetto with them.

Boris worked in a metal shop in a Lithuanian factory with a forced labor brigade from the ghetto before working for another blacksmith. In April 1943, the Jewish Police came after him again, stating that his papers were not in order. He was taken to another work camp, Koschedaren, where he worked for three months. At the end of the summer, Boris was sent back to the ghetto.

Around this time, talk of resistance was circulating throughout the ghetto. At the beginning of 1943, the Soviets began dropping special agents by parachute to organize resistance units in Lithuania. A friend of Boris’ family helped him make connections that enabled him to join the resistance. A truck came one night, taking Boris and over twenty others out of the ghetto under the Germans’ noses.

Once they were out of the city, the truck dropped them off, and guides took the recruits into a forest where the partisans lived. After three long nights of walking, they arrived at the camp. Right away, the Russian partisans treated the Jews poorly. Boris immediately noticed the different motives of the Jewish partisans compared to their Russian counterparts. The Jewish fighters came to avenge the innocent blood of their family and friends, while the Russians simply wanted to survive and drink, causing friction between the two groups. Jewish women were often accosted by the Russians and their husbands killed. The Jewish partisans felt that if the Germans did not kill them, they would certainly be killed by the Russians, Poles, or Lithuanians.

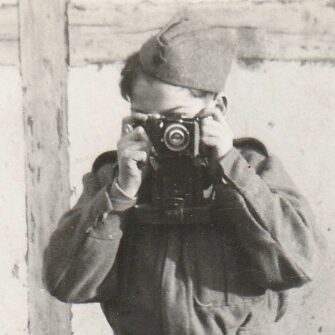

The group was divided into three units. Jewish casualties were extremely high in Boris’ group, “Death to the Occupiers.” Boris went on missions to sabotage German trains, railroads, and bridges, cut communication lines, and also helped gather food for the group. On June 22, 1944, the Russian Army pushed forward toward Minsk and came closer to their forest. In mid-July, Boris’ unit was on the outskirts of Vilna, which was not yet liberated. He was on guard duty when a hand grenade exploded near him. Boris lost his right hand and his left eye. His legs were covered in scars from shrapnel, and his feet were mangled.

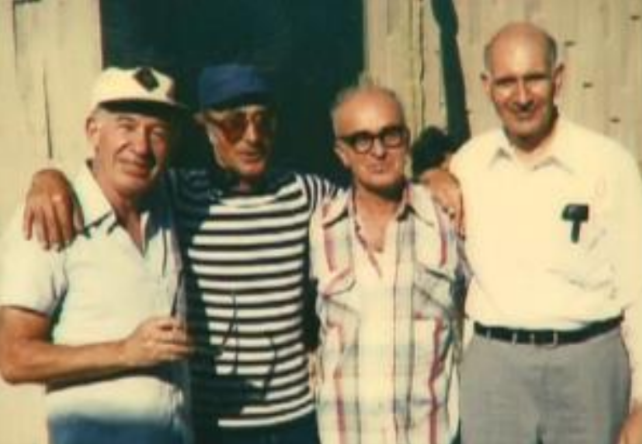

Boris’ friends (including Professor Dov Levin) carried him on their shoulders to a Polish first aid station before coming upon two Lithuanians, forcing them to carry their friend. Boris spent nine months in a Soviet military hospital and had five operations. During this time, he managed to make connections with his relatives in Moscow. They were reunited in March 1945.

After leaving Moscow after several months, Boris returned to Kovno. However, there was nothing left to keep him there. Boris had been a Zionist his entire life. He decided to make false papers and immigrate to Palestine. With the help of Bricha, an underground Jewish organization, Boris escaped through war-torn Europe to Germany, where he stayed in a Displaced Persons camp in the American Zone for three years. There he was welcomed by the Americans, who treated him with great kindness. He worked part-time for the historical commission and the canteen.

Boris’ plan to immigrate to Palestine changed when the War of Independence began in 1948. He contacted his paternal Aunt Gussie in New York and asked if she and her family would sponsor him. She couldn’t because they had already agreed to sponsor his cousin Lenny (the only other family member in Lithuania who survived), but she knew that Boris had a maternal uncle, Jackob Glass, in Everett, MA. She contacted his uncle, who agreed to sponsor Boris.

In 1949, Boris arrived in Massachusetts. He was warmly welcomed by his uncle, aunt, and cousins, whom he lived with for several months before co-owning a smoke shop with his cousin. One day, Boris went to a dance for the New Americans at the Green Manor and met Barbara Zelda Sneierson. It was love at first sight, and they were married in 1952.

Boris recognized October 28th as his parents’ yahrtzeit. Twelve years after their death, on October 28, 1953, Boris and Barbara’s daughter Rachel Sheila (named after Boris’ mother, Celia) was born, followed later by their son Isaac. Boris and Barbara had one grandchild, Tamara Esther Lewis.

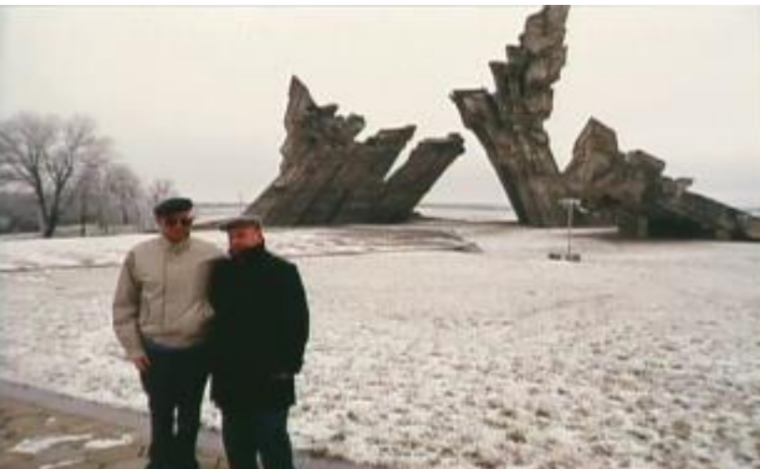

Boris held various jobs throughout his life in America, from owning a toy store to working in real estate. In 1995, Boris returned to his hometown of Kovno with his son, Isaac. He was very proud of his Jewish identity and shared his Holocaust experiences with the USC Shoah Foundation in 1996 to educate future generations on the lessons of the Holocaust. Boris passed away on January 28, 1997, after a year of battling cancer. His wife Barbara passed away on April 12, 2012.