Antal (born as Adolf) Oppenheimer was born on January 17, 1910, in Budapest, Hungary. His early childhood was spent in the vicinity of the Franz Joseph Castle around the time of the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The Oppenheimer family lived there at the invitation of a wealthy banker, who even gifted Antal with his own pony. Thanks to his grandmother, who managed a prestigious private club and the renowned Japanese Coffee House in central Budapest, Antal’s childhood was surrounded by the era’s intellectual elite—writers, artists, and poets who shaped the cultural life of the time.

Antal’s father, Hugo Oppenheimer, was a charismatic, bohemian figure. In 1913, Hugo journeyed to America, returning to Budapest with the intention of bringing his wife, Fani, and Antal to the United States. However, the outbreak of World War I left the family stranded in Hungary, where they would later endure the horrors of the Holocaust. Antal had seven sisters and a brother who were born after WWI.

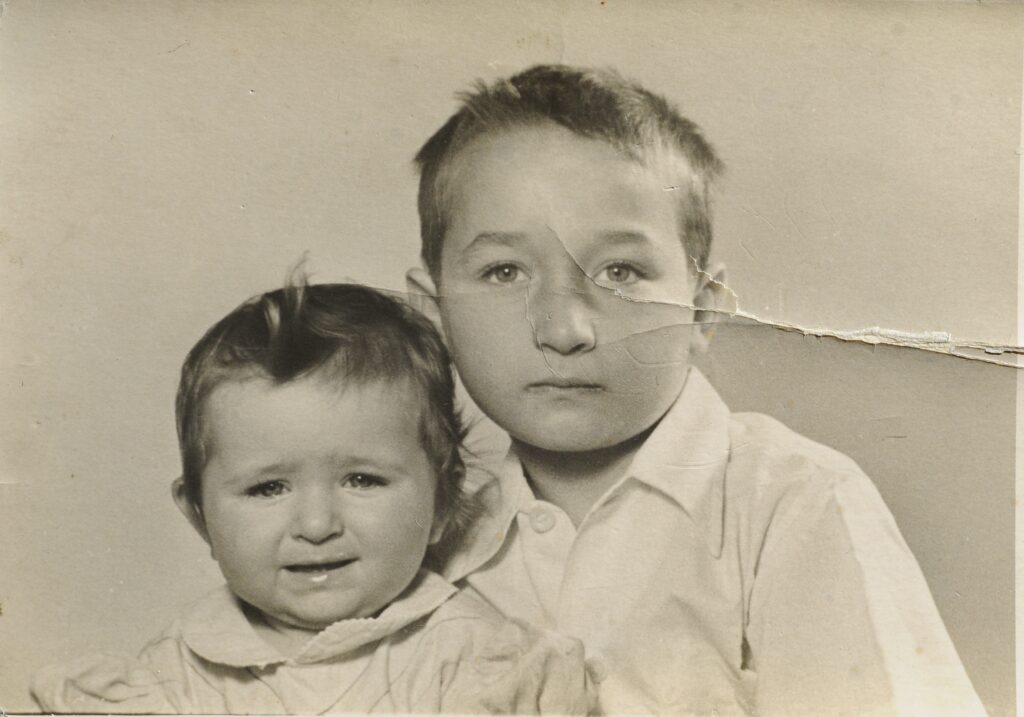

In 1938, Antal married Manci Margit at Budapest Dohany Syangoge. Their son, Vilmos, was born on the eve of Rosh Hashanah in 1940. Antal was a cloth trader and sold fabrics mainly to priests and wealthy individuals in the area.

After the outbreak of World War II, Hungary allied with Nazi Germany. In December 1942, Jewish men were drafted into the Jewish Labor Service to perform forced labor. Before Antal received his notice for forced labor, his wife, Margit, took him to seek a blessing from the “Miracle Rabbi,” likely at the synagogue on Dob Street in Budapest’s 7th district. The rabbi blessed Antal and gave him a coin for protection.

Like so many others, Antal was soon sent to the Eastern Front and endured brutal working conditions under the watch and cruel treatment of Hungarian and German soldiers. After multiple attempted escapes from labor sites in Hungary, Antal was taken to Ukraine in the spring of 1943 with a company assigned for punishment. During one escape attempt, he jumped from a moving train together with two fellow laborers. One of the three was shot and killed. In that moment, Antal threw away the coin he had received from the Miracle Rabbi.

The company was in Berdychiv for two weeks before marching for two days to Myropil. They were then taken to Kaczynski Camp, where they dug bunkers, trenches, and built fences. The Germans and Hungarians made the laborers undergo work that could have been fatal. The Germans were fearful of partisans in the area. The Jewish laborers were made to walk on roads where it was presumed that partisans had laid mines.

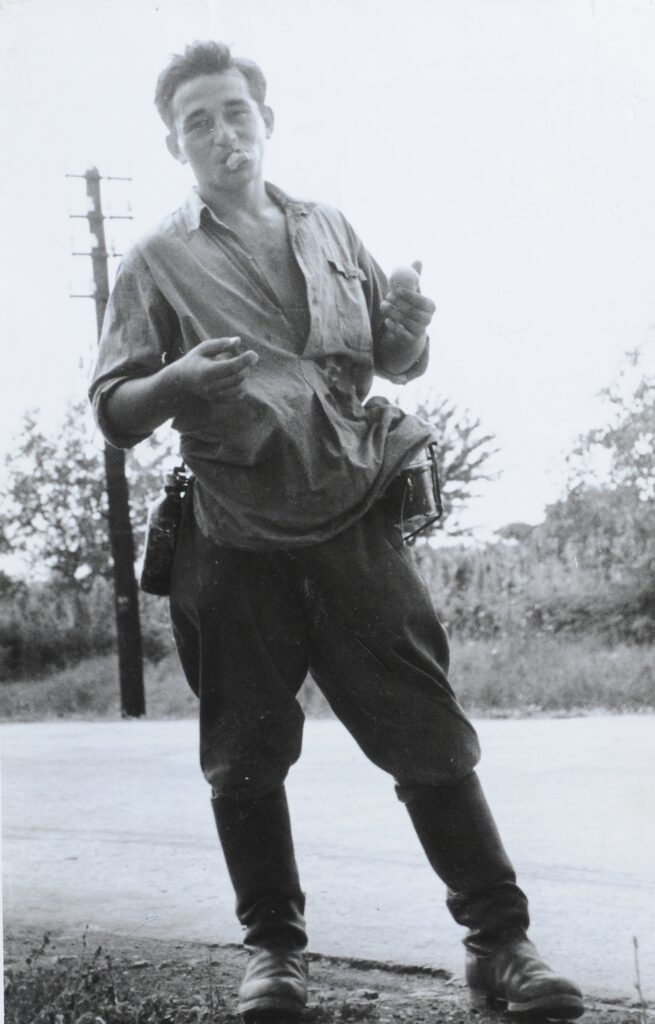

Never an hour went by without Antal thinking about escaping and joining the partisans. On August 3, 1943, the company arrived in Davyd-Haradok. Late that night, Antal and two others lagged behind and managed to escape into the darkness. After a few days, they made contact with the Soviets partisans in the forest. Antal received four weeks of training and was given a rifle. He took the partisan oath in October 1943, becoming a member of the Stalinskaya Brigade. In a letter to his wife and young son, Antal wrote that he had “gone to the forest.”

The Stalinskaya Brigade carried out operations in and around the Pripyat swamps, Pinsk, Chernihiv, and Zhytomyr. Antal’s first mission was to destroy a railway track. Antal and seven partisans in his squad made preparations at their assigned places, lying down about two meters from the track. When they heard the train approaching and received the signal, they crept forwards and placed the explosive onto the side of the rail. They lit the black fuse wire and dropped down flat when the first explosion occurred, which was followed by a total of eight. The train was destroyed, and Antal’s first mission was a success.

In early November 1943, the brigade relocated to a place in the forest between Zhytomyr and Kiev, where they had fully equipped bunkers. At that time, the brigade had grown to four hundred fighters. Antal’s squad consisted of eleven men and one commander. At the end of December 1943, the Chepgi Brigade joined the unit. Every night for a whole week, the partisans received weapon consignments, which were dropped by aircraft.

On May 1, 1944, Antal’s group took a seven hour break at the village of Antoniewska as they moved towards the Janów area. The partisans and the residents of the village gathered together and sang the Polish and Russian anthems followed by the Internationale. For a brief moment, the village became an island of peace despite being surrounded by the noise of war. German soldiers were stationed only within a few kilometers, yet residents and special units secured the area, allowing this short-lived celebration to take place. Antal recalled this as an unforgettable event. The commander assembled everyone and asked them to sing their own anthems. Antal had never cried as deeply as he did then. Everyone was crying, thinking of home and family.

Around this time, the partisans were getting news of the successful advances of the Soviet army. Antal’s brigade crossed the Bug River and entered the Janów Forest, where they joined up with two Polish partisan groups – the Vanda Wasilevski and the Bogdan brigades – and carried out missions in several smaller units. Antal’s unit planted mines and cut down trees to block roads with a detonation wire attached to the logs. When the logs were moved by the enemy, the wire was pulled and exploded.

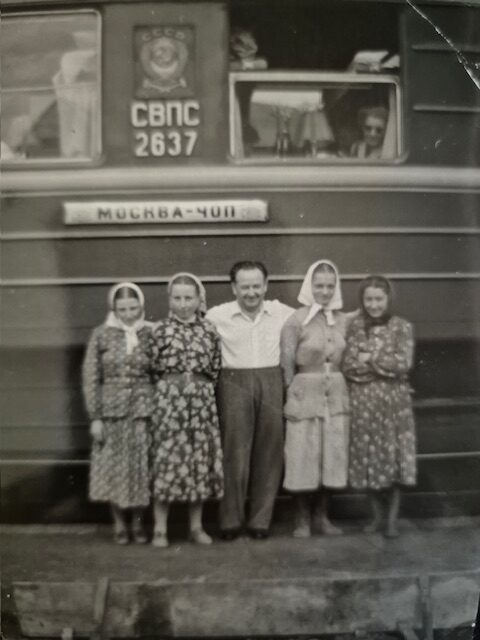

Antal participated in one of the largest partisan battles recorded in Polish and Soviet wartime history—the clash in the Janów Forest near Branew, on June 14, 1944. The Nazi forces suffered an estimated 1,500 dead and over 2,000 wounded in twelve hours of intense combat, marked by at least fifty separate engagements. In the late summer of 1944, Antal’s brigade moved into the Carpathians, where their main objective was to destroy roads, bunkers, and railways. At that time, the Germans were retreating at a great speed, both by road and by railway, and the partisans’ task was to prevent the retreat.

In the spring of 1945, Antal was transferred to the Budapest Soviet Headquarters, where he reunited with his family. His parents and four of his siblings survived: his brother Karl and three sisters, Etus, Elisabeth, and Eva. Etus had gone into hiding. Elisabeth, Karl, and their parents survived the Budapest Ghetto, and Eva survived Mauthausen Concentration Camp, along with Manci’s sister, Edit.

Manci had risked everything to protect their son, Vilmos, hiding him in multiple villages with relatives. In the summer of 1944, Manci, her sister Edit, and Vilmos moved into the Yellow Star house at Tisza Kalman square. Starting in June 1944, Jews in Budapest were forced out of their homes and into Yellow Star houses. These houses were designated for Jews as a preparatory step for deportations. Manci had fake papers and worked during the day as a pastry chef. Edit, still a child herself, took care of Vilmos.

In November 1944, Manci was taken to the brick factory in Obuda and endured a forced march to the Lichtenworth Concentration Camp in Austria. Manci left Vilmos in the care of her housekeeper. This woman, in a remarkable act of courage, protected the child by moving in with a member of the Arrow Cross (Hungarian fascist party), effectively disguising the boy’s Jewish identity.

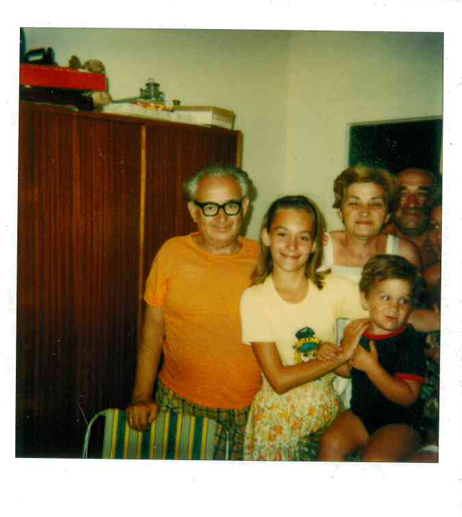

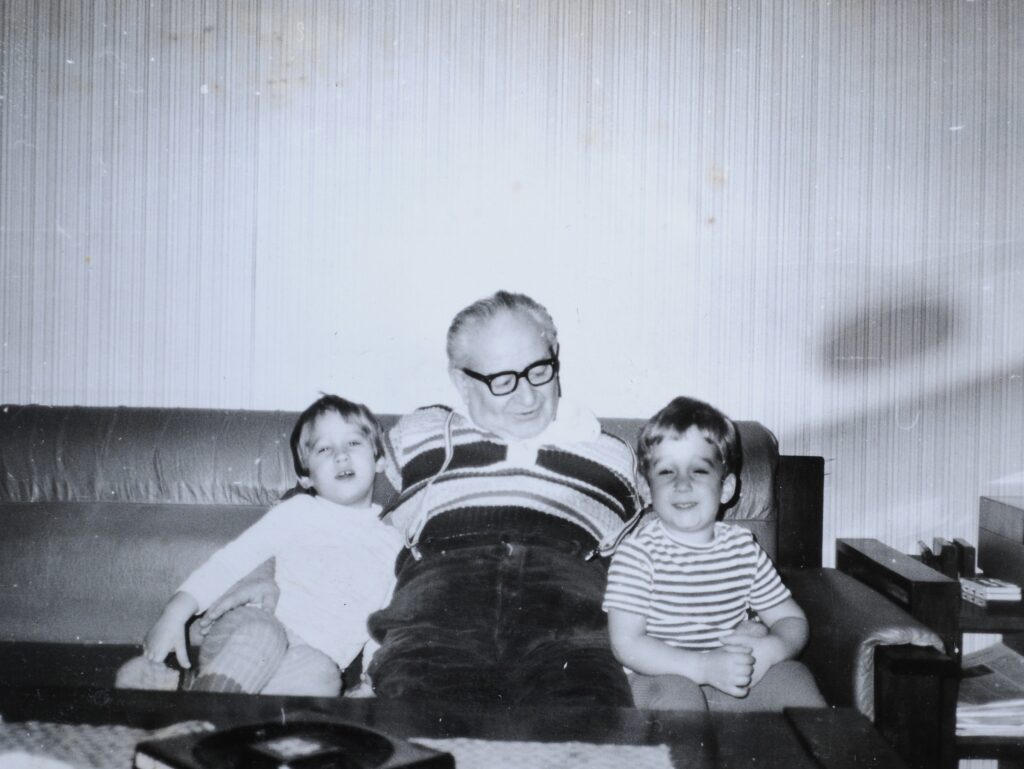

In April 1945, Manci returned to Budapest weighing only thirty-five kilograms. At Antal’s request, he was discharged at the Soviet Headquarters on April 30, 1945. Antal, Manci, Vilmos, and Manci’s sister moved to Mátyás Square in Budapest. They lived there until 1946, after which they relocated to Budakeszi, where they remained until 1956. Antal and Manci’s daughter, Judit, was born in October 1947.

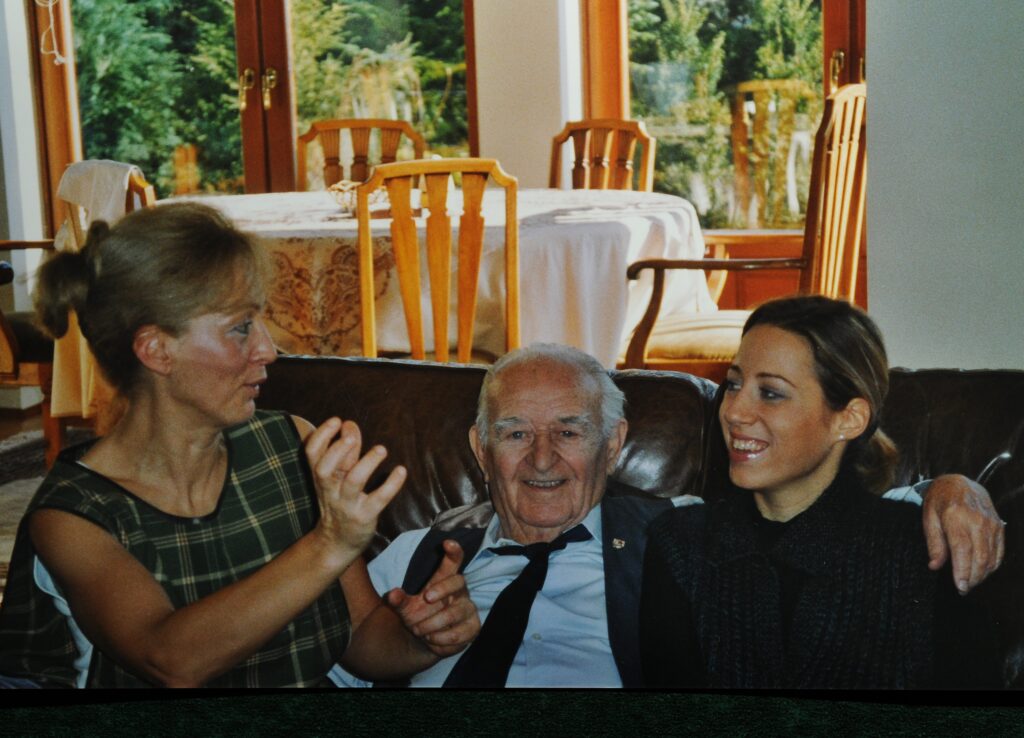

Antal served as the head of the Procurement Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a few years after the war. His dismissal from the ministry devastated him during the early communist period. From 1949 to 1951, he worked as an unskilled labourer at the Budapest foie gras processing plant. Beginning in 1951 and continuing until his retirement, he was employed as a site manager at the Mining Construction Company. In the late 1960s, the family moved to the 11th district of Budapest, near the Partizán Association, where Antal regularly attended meetings. They had a small weekend house at Lake Balaton, where the whole family spent the summer together until the mid 1990’s.

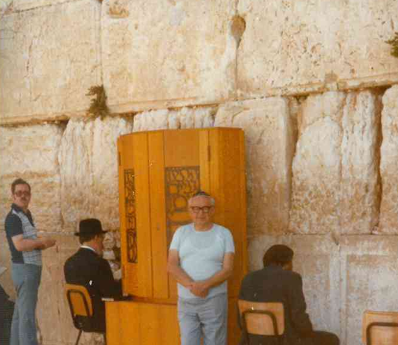

Antal and Manci had two children, Vilmos and Judit, and three grandchildren, Kinga, Nati, Ivan (Ariel). Antal passed away in April 2008. Antal and Manci’s survival stands as a testament to the resilience, resistance, and quiet heroism of those who risked everything to save others.